Chronic Subdural Hematoma Symptoms: How Long Before They Show?

A chronic subdural hematoma is a very slow bleeding in the brain.

Just when you thought you were in the clear for having a brain injury, this kind of bleeding could rear its ugly head.

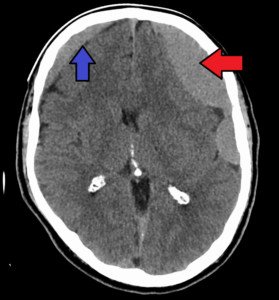

In fact, a CAT scan taken 24 hours after getting hit in the head may be perfectly normal, and then weeks go by without any problem, and then one day the patient awakens with symptoms: a chronic subdural hematoma is at work.

How Long It Takes for Symptoms of Chronic Subdural Hematoma to Start Showing

I wondered if there was a “grace period” during which the symptoms of chronic subdural hematoma would present, and then if there was a period of time following getting hit in the head, that if a patient still didn’t have symptoms, he could rule out chronic subdural hematoma.

Obviously, the hit that I took on my head two years ago, to this day, has not produced any symptoms.

So I can safely assume that I currently don’t have a chronic subdural hematoma, even though in theory, I could have developed a very small one without symptoms several weeks after the trauma, which resolved on its own.

But is there a grace period?

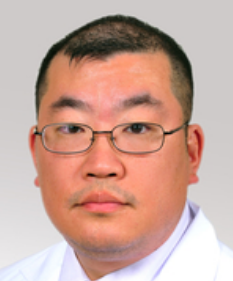

“There is no good answer for this question, as symptoms will be very dependent on a number of factors such as the age of the patient, variability with the amount of atrophy, the degree/severity of the trauma, history of other risk factors such as anticoagulant use, etc.,” explains Kangmin Daniel Lee, MD, a neurosurgeon with New Jersey Brain and Spine.

Old age is a major risk factor for chronic subdural hematoma, though younger people can get these as a result of blunt trauma to the head.

In fact, young children are more likely to get a chronic subdural hematoma from head trauma than young adults or middle aged adults.

Combine old age with daily use of anticoagulants such as aspirin or Coumadin, and you up the ante for the risk of developing a chronic subdural hematoma if the person hits his head as a result of a slip-and-fall, or bumps his head when getting into a car, or strikes his head on the underside of a table after being on all fours searching for a dropped coin.

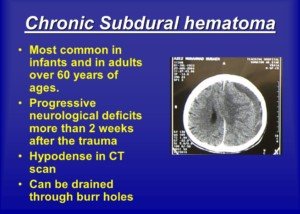

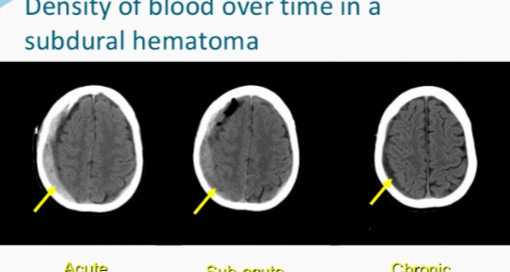

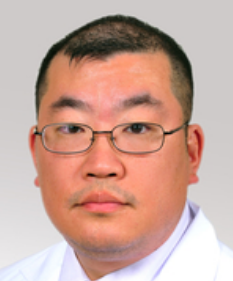

“The average length of time between head trauma and presentation to the emergency room is typically one month in the case of chronic subdural hematoma.

“This is likely due to the slow and progressive nature of symptom onset. The age of the hematoma is easily confirmed by observing the density of the blood on CT scan.”

If you hit your head, or get hit in the head, even if it doesn’t cause immediate symptoms like a headache or dizziness, you still should take note of the date it happened.

The reason is … you may feel fine for several weeks, then awaken one day with out-of-the-blue symptoms, like my mother did:

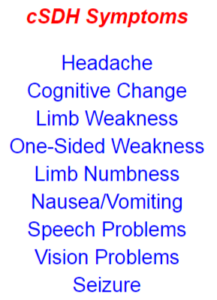

A headache that she described as feeling like a “crown of thorns” that wouldn’t respond much to painkillers; significant leg weakness (one leg more so than the other) that made it nearly impossible for her to stand up from a chair; and upchucking.

This occurred six weeks after she lost consciousness from a blood pressure drop while standing, and fell dead-weight against the bathtub, striking her head. The diagnosis was a chronic subdural hematoma.

Just one week before the sudden onset of the symptoms, my mother had attended an exercise class and reported that it was too easy for her!

Chronic subdural hematoma is a very stealthy condition, and if symptoms appear, you absolutely must seek medical treatment.

Dr. Lee focuses on minimally invasive techniques to treat traumatic and degenerative diseases of the spine and brain tumors. He’s been invited to speak at the regional and national levels on his research areas.

Dr. Lee focuses on minimally invasive techniques to treat traumatic and degenerative diseases of the spine and brain tumors. He’s been invited to speak at the regional and national levels on his research areas.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.

Top image credit: James Heilman, MD

Can Chronic Subdural Hematoma with Symptoms Go Away on Its Own?

Burr hole drainage of a chronic subdural hematoma

If a chronic subdural hematoma causes symptoms, does this mean it cannot resolve on its own, without medical treatment?

After all, many elderly people (and younger people who get hit in the head), who don’t have medical coverage, and who develop chronic subdural hematoma, won’t seek medical attention if the symptoms are mild.

Also, in an elderly person, if the symptoms are mild enough, they can be brushed off as a sign of aging, or the result of “working too hard” the day before.

In fact, when my mother awakened with a searing headache (and was later diagnosed with chronic subdural hematoma), my father actually believed that the headache was caused by eye strain from sewing too much the day before!

“It is possible for cSDH to resolve on its own,” says Kangmin Daniel Lee, MD, a neurosurgeon with New Jersey Brain and Spine. (He was not my mother’s surgeon.)

But this refers to chronic subdural hematoma without symptoms.

If a chronic subdural hematoma doesn’t produce symptoms, then how would doctors even know a patient has one in the first place?

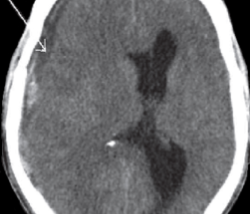

It is discovered incidentally on a CAT scan of the head that’s taken for either an unrelated reason; or, a tiny chronic subdural hematoma is discovered in addition to the bigger one that’s causing some symptoms. This was the case with my mother.

She had a CAT scan with contrast dye of her head because the ER doctor suspected a mild stroke.

But then the ER doctor came back and stated, “You didn’t have a stroke. But what we found surprised us. You have bleeding in the brain. Did you fall recently?”

(The fall had been six weeks prior, in which she’d hit her head on the bathtub.)

There were two chronic subdural hematomas in my mother’s brain. One was “large” and the other was “small,” at just four millimeters.

Only the large one was surgically drained (via a 15 minute procedure). We were told that the small one would resolve on its own.

It never produced symptoms (after the surgery my mother didn’t exhibit the profound weakness in her legs that she had that got her the ER visit in the first place).

A follow-up CAT scan verified that the four-millimeter chronic subdural hematoma eventually vanished completely.

So yes, a chronic subdural hematoma without symptoms can resolve on its own.

Dr. Lee says, “This will take weeks to months depending on the volume of blood present.

“However, if the patient is symptomatic from the hematoma, then this usually will indicate that the volume of blood has gotten thick enough to cause mass effect on the brain.”

The term “hematoma” is derived from Latin and translates to “blood mass.”

Dr. Lee continues, “If the volume is large enough to do this, then the likelihood is greater that there will be repeat hemorrhages, causing even more mass effect, which would be dangerous for the patient.

“This is because the hematoma actually pushes the brain away from the skull, stretching the tiny bridging veins and increasing the likelihood of further hemorrhage.

“If the vein bleeds then there is often a snowballing effect making things worse and worse.”

Between the ages of 50 and 80, the brain’s weight decreases on average by 200 grams, says Dr. Lee.

Corresponding to this is an increase in the space between the brain and skull from 6 to 11 percent of the total intracranial space.

These conditions increase the likelihood of chronic subdural hematoma from a fall in the elderly.

A chronic subdural hematoma typically shows symptoms weeks after the trauma to the head, when head trauma is the cause.

A chronic subdural hematoma typically shows symptoms weeks after the trauma to the head, when head trauma is the cause.

In fact, a CT scan taken 24 hours after getting hit in the head may be perfectly normal.

And then weeks go by without any problem, but then one day the patient awakens with symptoms: a chronic subdural hematoma is at work.

Dr. Lee focuses on minimally invasive techniques to treat traumatic and degenerative diseases of the spine and brain tumors. He’s been invited to speak at the regional and national levels on his research areas.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Chronic Subdural Hematoma Symptoms vs. Stroke

The symptoms of a stroke and a chronic subdural hematoma are strikingly similar — nearly identical — and in some cases ARE dead-on identical, even though the causes of these conditions are quite different.

For this article I consulted with Kangmin Daniel Lee, MD, a neurosurgeon with New Jersey Brain and Spine.

Distinguishing at home the difference between the symptoms of stroke and those of chronic subdural hematoma.

My mother had a chronic subdural hematoma and I thought she’d had a minor stroke. So did the ER doctor after examining her.

In fact, the ER doctor didn’t even offer the differential diagnosis of chronic subdural hematoma.

All I heard was possible stroke. Dr. Lee (who was not my mother’s neurosurgeon) explains:

“There is too much overlapping symptoms with chronic subdural hematoma vs. stroke to be able to reliably diagnose one or the other simply based on clinical presentation.

“Most often, patients with chronic subdural hematoma will complain of gait instability, headache, confusion, language difficulty or weakness. These are also common presenting complaints of stroke.”

My mother’s sudden onset of symptoms began early in the morning with a raging headache, and when she got out of bed, it was clear that there was a compromise in her ability to walk.

Though at that time, I passed it off as a side effect from the headache – who wants to march across the room while suffering the meanest headache ever?

But as the morning progressed I clearly observed something not right with my mother’s walking, and what was particularly alarming was that the left leg had a slight drag.

There was profound weakness in her lower body that made it extremely difficult for her to get out of a chair.

Her speech and cognition were normal, but normal speech and cognition don’t rule out a stroke.

Though slurred speech and/or confusion are common symptoms of stroke (and chronic subdural hematoma), the absence of one or both of these does not point more likely to stroke, or more likely to chronic subdural hematoma.

I then wondered about the symptom of sudden-onset double vision, which can occur from a mini-stroke, also known as transient ischemic attack.

Deductively, sudden-onset double vision can also be a symptom of a full-blown stroke.

But can a chronic subdural hematoma cause sudden-onset double vision?

And are there symptoms of a stroke that would never be caused by a chronic subdural hematoma?

Dr. Lee responds, “Unfortunately there really are no clinical symptoms that would necessarily distinguish between the two.

“The clinical symptoms of a stroke are dependent on the clinical function of the brain tissue that is damaged.

“Both present commonly with headache, seizure, weakness, numbness or altered mentation.

“In terms of timing, one could say that stroke is more commonly associated with an acute presentation, while cSDH will generally occur gradually and progressively.”

This is a compelling point, because my mother had two incidents of chronic subdural hematoma:

1) sudden onset of symptoms six weeks after hitting her head, and

2) 10 days after drainage of this cSDH, her left hand began losing function, and marginally altered mentation began setting in – both in a subtle way – and both caused by a recurrence of the original chronic subdural hematoma (there is a 15 percent recurrence rate).

There was nothing “acute” about this second set of symptoms.

There was a progressive component; each day the left hand got worse, and each day the headaches got worse and more prolonged.

Stroke was the fartherest thing from my mind, based on my mother’s very recent history of chronic subdural hematoma, and the progressive nature of her new symptoms.

But note that Dr. Lee says: “However, this is not a hard and fast rule, as chronic subdural hematoma can also cause acute symptoms such as altered mentation or weakness.”

The first incident of chronic subdural hematoma in my mother, as mentioned already, were acute in that in the weeks prior, she was doing great, zipping all over the place at stores, and the night prior to her awakening with a headache that was bad enough to bring her to tears, she was completely normal.

Next morning, bam! Disabling headache pain along with severe lower body weakness.

The only way to differentiate between stroke and chronic subdural hematoma, regardless of symptoms, is with a CT scan of the brain.

Don’t assume that someone’s symptoms must mean chronic subdural hematoma just because he hit his head recently, either; it can still be a stroke, unrelated to the head trauma.

Dr. Lee focuses on minimally invasive techniques to treat traumatic and degenerative diseases of the spine and brain tumors. He’s been invited to speak at the regional and national levels on his research areas.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.

Top image: Shutterstock

Signs of Chronic Subdural Hematoma Recurrence

You may need to really be on the ball to catch the early symptoms or signs of a recurring chronic subdural hematoma.

These new-onset symptoms won’t necessarily be the same as the original ones. The recurrence rate is 5 to 33%.

My senior-aged mother developed a chronic subdural hematoma.

“A chronic subdural hematoma occurs when blood collects on the surface of the brain beneath the dura, which is the covering of the brain,” says Dr. David Beatty, MD, a retired general practitioner with 30+ years of experience and an instructor of general medicine for 20+ years.

“Rupture of cortical bridging veins occurs. These veins connect the venous system of the brain to the intra-dural venous sinus.

“Sometimes there is a history of head trauma, but this is often only a minor knock which may have happened days or weeks earlier.

“In about 50% there is no recollection of head injury.”

Six weeks prior to the first symptom of my mother’s cSDH, she had lost consciousness due to orthostatic hypotension, fell and hit her head on a bathtub. At the time she was on Coumadin, a blood thinner.

She stopped the Coumadin 12 days later due to the fall risk of orthostatic hypotension, but continued on daily aspirin for recent coronary bypass surgery.

Thus, the neurosurgeon (after cSDH diagnosis) was not able to pin down the cause of the chronic subdural hematoma.

Six Weeks After the Fall

One morning she awakened around 7 am with a splitting headache that made her weep and unable to function. It persisted for three hours until painkillers finally subdued it.

Her walking was very feeble, and she also upchucked.

With difficulty she made her way down the stairs and sat in a chair, reporting that the headache was gone. But she had extreme difficulty rising from the chair.

She was not able to walk normally; was weak and very tired. Her left leg slightly dragged behind the right.

All these symptoms suggested a mild stroke, but at the ER she was diagnosed with chronic subdural hematoma.

Ten days after a burr hole craniotomy was the first time that a definitive new symptom appeared, though at the time, I didn’t think this was a recurrence of the chronic subdural hematoma.

About nine or ten days after the burr hole procedure, I noticed that my mother seemed marginally foggy, but chalked it up to just overall general recovery, and a very recent adverse reaction to an anti-seizure drug, Keppra, that was prescribed for the chronic subdural hematoma.

She had been regaining her strength after the adverse drug reaction, but then seemed to be regressing as far as energy.

Since the surgery my mother had complained of headaches, but they weren’t bad enough to alarm me; I thought they were post-surgical, or related to the incision.

New Symptoms

But ten days after surgery I began noticing some quirky mental things.

Then she began dropping things by accident. Ultimately it was determined that the dropping was coming from her left hand.

She was not able to touch her left index finger to her nose with eyes closed. That’s when I knew there had to be a recurrence of the chronic subdural hematoma.

Also, over the past several days her headaches had increased in frequency and intensity, to the point where she’d moan and groan.

I got ahold of the neurosurgeon and reported loss of fine motor control in my mother’s left hand.

She struggled to pick up a straw, dropped cups of juice and a bowl of potato chips, dropped her glasses and accidentally stepped on them and didn’t realize it, and dropped other items like a roll of masking tape, the TV remote and some mail.

The neurosurgeon wasn’t concerned and never suggested this might be a recurrence of the chronic subdural hematoma!

One mental incident stood out. She had a few pills in her left hand, about to take them, then suddenly went to a chair and lifted a magazine off it with her right hand, then placed the magazine back down, pills still in left hand. I asked why she did that.

She said, “I’m looking for my pills.” Then she realized they were in her left hand.

Overnight she was awake most of the time, loudly groaning from headache pain.

At 7 am she was stuttering, speech mildly slurred, or, to put another way, lacking its usual crystal clarity, and her mentation was altered (e.g., kept insisting, and trying, to go upstairs to sleep despite having to get ready for an appointment with the neurosurgeon).

We were running behind schedule, yet she insisted on using her impaired left hand to lift a glass bottle of juice from the top shelf of the refrigerator. I had to remove the bottle from her flaccid hand.

She then wanted to make up her face, despite my protests that we were going to be late, and she didn’t seem to notice she was repeatedly dropping things in the bathroom.

I finally had to place my hands on her and make her walk into the garage.

Ultimately, she was diagnosed with a recurrence of the chronic subdural hematoma.

As you can see, the symptoms the second time around were different than the first time, save for the headache.

Dr. Beatty has worked in primary medicine, surgery, accident and emergency, OBGYN, pediatrics and chronic disease management. He is the Doctor of Medicine for Strong Home Gym.

Dr. Beatty has worked in primary medicine, surgery, accident and emergency, OBGYN, pediatrics and chronic disease management. He is the Doctor of Medicine for Strong Home Gym.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.

Source: medschool.lsuhsc.edu/neurosurgery/nervecenter/chsdh.html

Can Chronic Subdural Hematoma Be Fatal if Untreated?

Is it possible for a chronic subdural hematoma to be fatal, being that the bleeding in the brain is slow?

Chronic subdural hematoma, unlike the acute (rapid bleeding) version, gives the patient plenty of time to get to the emergency room for treatment.

Chronic Subdural Hematoma Causes Slow Motion Brain Bleed

Unless the patient lives in the jungle or in a poorly developed nation with rudimentary medical facilities, he or she will see a doctor when the symptoms of chronic subdural hematoma begin developing.

Maybe not right away, but eventually. The symptoms of chronic subdural hematoma may be so slow-developing and/or seemingly innocuous, that the patient might end up choosing to make an appointment with his primary care physician, rather than get to the ER pronto.

My mother had two bouts of chronic subdural hematoma (the second was a recurrence of the first, and the second-time symptoms started out subtlety and gradually, whereas the first-time symptoms started out with a bang).

Because symptoms of chronic subdural hematoma can mimic that of a stroke, or interfere with daily living (e.g., a horrendous and persistent headache), the patient typically won’t waste too much time getting to a doctor…

Unless he resides in a developing nation with no adequate medical care, or lives alone and has pre-existing depression or other mental illness that keeps him in bed, or lacking insight, as the symptoms of chronic subdural hematoma worsen.

“A small cSDH with no or minimal brain compression could be observed expectantly with serial CT scans,” says Kangmin Daniel Lee, MD, a neurosurgeon with New Jersey Brain and Spine. (He was not my mother’s surgeon.)

This happened with my mother who had two chronic subdural hematomas on her first CT scan, but only the bigger of them (the one that eventually recurred) was surgically drained.

The other one was only four millimeters and was only observed.

Dr. Lee continues, “It would be important to get ‘treatment’ in the form of adequate blood pressure monitoring and modulation,” regarding cSDH’s with no or minimal brain compression.

“Evaluation of blood work to diagnose coagulation disorders is also important.

“So there are a number of other treatments besides surgery that are necessary for an adequate evaluation of someone with a chronic subdural hematoma.

“In the situation where all of these other factors are monitored and controlled, a patient with a small chronic subdural hematoma could easily be observed and monitored without surgical intervention.”

The 4-mm chronic subdural hematoma in my mother resolved without treatment.

Dr. Lee says, “If no rebleeds occur and the SDH does not grow in size, then the SDH would likely eventually get reabsorbed.

Occasionally the SDH may just remain stable in size indefinitely, and if the patient has minimal or no symptoms, then no intervention would be indicated.”

My mother’s first set of symptoms were not minimal and could not be ignored. They started out with a headache of crippling proportion, along with profound weakness in her legs. Who can let something like this go untreated?

Can You Ever Die from a Chronic Subdural Hematoma?

Dr. Lee explains, “Chronic subdural hematoma can definitely be fatal, if reabsorption of the hematoma does not occur then, but in general patients do seek medical care prior to getting to this point.”

The day of my mother’s first occurrence, I took her to the ER. The recurrence, however, came on gradually, with its first symptom masquerading as a post-surgical daily headache that we thought would eventually stop. But it got worse.

And then came the accidentally dropped items that, initially, masqueraded as lack of attention.

But when my mother couldn’t place her left index finger to her nose while her eyes were closed, and when she struggled to pick a straw up with her left hand, I knew that the chronic subdural hematoma was recurring.

Dr. Lee says, “There is very little data regarding mortality of untreated chronic subdural hematoma.

“This kind of data would be generally difficult to collect, but mortality from chronic subdural hematoma after surgical treatment is low – about 13 percent.”

Dr. Lee focuses on minimally invasive techniques to treat traumatic and degenerative diseases of the spine and brain tumors. He’s been invited to speak at the regional and national levels on his research areas.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.

Top image: ©Lorra Garrick

Does Vomiting After Coronary Bypass Mean Something Serious?

If a person vomits after coronary bypass surgery (CABG), is this significant?

One must also consider how long after the coronary bypass surgery that the patient began vomiting.

Has the vomiting been ongoing since immediately following the CABG?

Or did the vomiting start up several days, or a week or so, after the coronary bypass surgery?

“Vomiting is poorly understood since it not only is caused by direct irritants to the stomach, but also by certain smells, tastes, sights, and even by motion,” says Dr. Michael Fiocco, Chief of Open Heart Surgery at Union Memorial Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, one of the nation’s top 50 heart hospitals.

“After CABG, vomiting is usually a sign of poor gastric (stomach) motility.

“This is more prevalent in diabetics who are notorious for having poor gastric emptying.”

Diabetes is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease. But many coronary bypass patients are not diabetic.

Dr. Fiocco continues, “Other causes include medication irritating the stomach and severe constipation.

“For patients in the hospital, you may be faced with three or four morning medications plus pain medication before being served breakfast.

“Insist on something to eat first, or nausea and possibly vomiting will be the result.

“No matter the cause, vomiting after CABG is not common and usually self-limiting.”

My mother had some bouts of vomiting after her quintuple bypass surgery.

It began in the hospital after she was moved to the cardiac recovery wing, and it was soon realized by staff that the vomiting was associated with a vaso-vagal response (orthostatic hypotension), which she began experiencing nine days after her coronary bypass surgery.

The orthostatic hypotension has resolved, but to this day, it has not been determined what the cause was.

The three suspects are:

1) Impaired vascular tone from the coronary bypass surgery,

2) Pacemaker syndrome (the first orthostatic episode occurred the morning after my mother had a pacemaker implanted … nine days after the CABG), or

3) Side effect from the anti-arrhythmic drug amiodarone (within a day and a half of my mother stopping this drug, the orthostatic hypotension began decreasing until it disappeared).

My mother had occasional miscellaneous bouts of vomiting in the weeks following the coronary bypass surgery, that were not related to orthostatic hypotension.

Most of this vomiting occurred while she was struggling with constipation on the toilet (at home).

Another instance of at-home vomiting apparently was related to the emotional turmoil caused by the coronary bypass surgery.

Immediately following coronary bypass surgery, a patient may vomit as a result of the general anesthesia.

Dr. Fiocco specializes in treating artery disease, valvular disease and aortic aneurysm. His heart care expertise has earned him recognition by Baltimore Magazine as a Top Doctor in 2010, 2011, 2013, 2016 and 2017.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.

Top image: Freepik.com/ stefamerpik

What Does Abdominal Pain After Coronary Bypass Mean?

Abdominal pain after coronary bypass surgery can be mild or considerable, and make the patient think something is wrong.

Pain can be frightening, especially after coronary bypass surgery (also known as CABG).

“This is an extremely common problem which in the vast majority of cases is benign and self-limiting,” says Dr. Michael Fiocco, Chief of Open Heart Surgery at Union Memorial Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, one of the nation’s top 50 heart hospitals.

So then, what are some causes of post-op pain with coronary bypass surgery?

Dr. Fiocco continues: “The most common causes are pain from the drains which exit the body in the upper abdomen, causing some pain and occasional muscle spasm and constipation.

“The discomfort from the drains subsides when the drains are removed 48 hours after surgery.

“Constipation is usually resolved before discharge, but may linger depending on the patient’s level of activity and their use of narcotic pain medicine.

“More narcotics, less activity, means more constipation. These common causes of abdominal pain rarely last for more than a few days and the pain is usually quite mild.”

But if the pain is more than mild, say, approaching a 7 or 8 on the hospital’s pain scale, where a rating of 10 means the worst pain you can imagine, this may reflect:

Simply the patient’s general physical condition (is the patient older, out of shape?)

The patient’s natural tolerance for pain

And if other issues are going on with the patient, such as clinical depression (primary or secondary), which can amplify perception of pain, and abdominal pain from coronary bypass surgery is no exception to this amplification.

There can also be more serious, though much rarer, causes of abdominal pain following CABG.

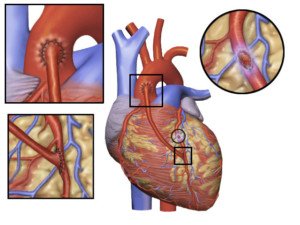

CABG. Source: Blausen Medical Communications, Inc.

Dr. Fiocco explains, “More concerning and fortunately very rare is pain from pancreatitis, bowel distention, and peptic ulcer disease. These disorders require longer stays in the hospital and close observation.”

What would be the course of treatment in the event of these complications following CABG?

“CT scans, upper and/or lower endoscopy, and frequent blood tests are needed to diagnose and treat these problems,” says Dr. Fiocco.

“They are rarely life threatening, but may be quite debilitating for several weeks.”

Can abdominal pain following coronary bypass surgery ever mean a life threatening situation?

“The most unusual cause of abdominal pain, but the most dangerous, is ischemic bowel, or loss of blood supply to the bowel,” says Dr. Fiocco.

“This occurs secondary to a clot or piece of plaque flowing downstream to the arteries of the intestine, similar to how a stroke affects the brain.

“This may require emergency surgery in its most severe form.

“The most important message for patients is that abdominal pain may occur after CABG, but is almost always self-limiting, mild and benign.”

Dr. Fiocco specializes in treating artery disease, valvular disease and aortic aneurysm. His heart care expertise has earned him recognition by Baltimore Magazine as a Top Doctor in 2010, 2011, 2013, 2016 and 2017.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.

Top image: Shutterstock/antoniodiaz

Chest Pain: How Long After Bypass Surgery Is It Normal?

Still having chest pain even after your coronary bypass surgery?

It’s understandable for a person, fresh from coronary bypass surgery, or even several weeks out, to think he’s having a heart attack or something wrong with his heart, when he has chest pain.

“Chest wall pain after cardiac surgery may normally last 3-6 weeks, but may last as long as 12 weeks on rare occasions,” says Dr. Michael Fiocco, Chief of Open Heart Surgery at Union Memorial Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, one of the nation’s top 50 heart hospitals.

Think of it this way:

A surgeon just cut open your chest. This involves “cracking” open the sternum and using a crank-like device to pry it apart to expose the sac that surrounds the heart.

Source: Shutterstock/mountainpix

After the bypass surgery, the surgeon reattaches the sternum, which is bone, using wire. Of course you will have chest pain after bypass surgery!

Dr. Fiocco explains, “This pain has a different quality from angina and most patients know the difference without question.

“Post-op pain is also related to movement, coughing, and normally can be reproduced with palpation of the chest wall, none of which occur with ischemic pain (angina).”

Palpation means feeling and pressing with your fingers against your chest.

“It’s extremely rare to have angina following CABG (coronary artery bypass grafting), and differentiating between angina and post-op pain should be simple with just a physical exam,” continues Dr. Fiocco.

Think of coronary bypass surgery as new plumbing for your heart.

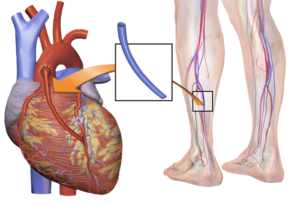

The new plumbing (veins harvested from your leg and/or arm) is free of the clogging and blockage that necessitated the operation in the first place.

As a result, oxygenated blood easily flows through these vessels, supplying your heart with oxygen.

Angina is chest pain that results from restricted blood (oxygen) flow to the heart.

Thus, the discomfort you feel following coronary bypass surgery, like Dr. Fiocco says, is typically related to motion and coughing. Coughing creates motion of the chest wall, which was just cut open.

Movement such as shifting positions in bed or even taking a deep breath, causes the chest cavity to expand or lift.

It was just operated on; chest pain is to be expected.

The chest pain may seemingly come and go for no apparent reason, but even subtle motion can bring it on.

Don’t let chest pain, that follows coronary bypass surgery, alarm you, even if you’re experiencing it weeks after.

However, it’s important to note concerning discomfort to your surgeon and cardiologist.

Dr. Fiocco specializes in treating artery disease, valvular disease and aortic aneurysm. His heart care expertise has earned him recognition by Baltimore Magazine as a Top Doctor in 2010, 2011, 2013, 2016 and 2017.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.

Top image: Shutterstock/Photographee.eu

Why Do I Have NO Appetite Since My Heart Bypass Surgery?

Of course you’ll have no appetite in the days right after coronary bypass surgery — but what if the appetite suppression persists?

Your appetite a few weeks after coronary bypass surgery may still be somewhat suppressed, though some patients will be eating quite heartily even one week out from CABG.

This depends on their preoperation eating habits, and whether or not they decide to change their eating habits for the better, post-operatively.

“Change in the taste of food after surgery is not unusual immediately after surgery, and mostly resolves with time,” begins Michael Fiocco, Chief of Open Heart Surgery at Union Memorial Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, one of the nation’s top 50 heart hospitals.

But there are numerous other reasons for losing one’s appetite after coronary bypass surgery.

Ten weeks after my mother had quintuple bypass surgery, she still had much appetite suppression.

“I have to force myself to eat,” she had said. From the get-go, she had no appetite in ICU, but ate a little more once she was moved to recovery.

Once she was home, she hardly ate, though there had been improvement as far as variety of food.

My mother was never a big eater, but the difference in her appetite post-surgery, and her appetite prior, was enough to have caused her weight to drop from 141/140 to 128, though sometimes it was 130.

Initially she claimed that all food, except eggs and potato chips, tasted like cardboard.

Even when Taste Is Normal, Appetite May Still Be Suppressed Weeks after CABG

CABG. Credit: BruceBlaus

Over time she began re-expanding the menu to include just about all foods — but in small amounts.

Eventually she was eating every type of food she normally ever did. Her taste had returned, but the appetite still remained suppressed for some time after that.

She had supposed that maybe her stomach had shrunk, and that it would take time to regain her appetite.

“Loss of appetite after surgery is well-described and poorly understood,” says Dr. Fiocco.

“It can be caused by persistent pain, constipation and depression, as well as many poorly understood factors.”

When Eating Less Causes Weight Loss

You might be thinking that weight loss from appetite suppression is a good thing for an overweight coronary bypass patient.

But what if the patient wasn’t overweight in the first place?

My mother is a senior citizen, had not been exercising and had not been eating much following the bypass surgery. This translates to loss of valuable muscle tissue.

A senior citizen cannot afford to lose muscle.

When they do, they become weaker; or, to put it another way, they are not as strong as they could be.

My mother is about 5-4, and when she was 128 pounds, she weighed as much as her 5-6 daughter-in-law. But there’s a huge difference in their body compositions.

The younger woman had been working out to the Insanity DVD series, and plus, she had an excellent appetite and hence, ate full meals.

Though she’s very lean in appearance, she has a healthy amount of muscle.

My mother has always had excess abdominal fat, and following the coronary bypass, had visible loss of muscle in her legs and arms.

My sister-in-law has tight, fit-looking legs and arms (though I think she can add more muscle), and hardly any fat in her abdominal area. In short, two entirely different body compositions were going on.

So what was the cause of my mother’s loss of appetite since her coronary bypass surgery? I don’t know, and neither did her doctors.

Solutions to Appetite Loss After CABG

Dr. Fiocco explains, “Patients with persistent problems will usually find relief through changing or eliminating medications.

“The suggested solutions are as numerous as the causes, including treating the above ailments, using supplements like Boost, eating small non-fatty meals, eating with other people, eating several smaller meals each day, and even stimulating your appetite with small amounts of dark chocolate.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing appetite loss following CABG, it will likely return, as did my mother’s.

Dr. Fiocco specializes in treating artery disease, valvular disease and aortic aneurysm. His heart care expertise has earned him recognition by Baltimore Magazine as a Top Doctor in 2010, 2011, 2013, 2016 and 2017.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.

Top image: Shutterstock/Photographee.eu

Best ER Test for Chest Pain; Rules Out Severe Heart Disease

Chest pain is frightening and if you’re in the ER, there’s a test you’d better request.

A test that research shows is very reliable for detecting a heart problem.

The best test, shown to be effective and safe, is the CTA (computed tomographic angiography), says a long-term study.

If you come to the ER with chest pain, you should have the CT angiogram done, says University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine research.

But ER doctors don’t always order this test for patients coming in with chest pain – certainly not in the case of my mother, who I took to the ER because of her chest pain. The CT angiogram was not ordered!

Troponin tests were, and this is standard for patients coming to the ER with chest pain. Eight million people go to ERs every year in the U.S. with chest pain.

However, 5-15 percent are actually having heart attacks or some other cardiac issue.

Over half are admitted to the hospital for observation and further testing (such as my mother after her second ER visit two days later; she had not had a heart attack).

Her next test was an echocardiogram to see if she was suitable for a treadmill stress test.

The echocardiogram was “abnormal,” so the next step was the invasive and risky catheter angiogram … which showed dangerously blocked coronary arteries; two hours later she was in the OR undergoing quintuple bypass surgery.

The CT angiogram is much safer in that it doesn’t carry the risks of blood clots, infection, stroke and cardiac arrest, like the catheter angiogram does, though these complications are rare.

The CT angiogram offers a faster and less costly way to determine which ER patients have had a recent cardiac problem.

“The ability to rapidly determine that there is nothing seriously wrong allows us to provide reassurance to the patient and to help reduce crowding in the emergency department,” explains Judd Hollander, MD, the study’s lead author, professor and clinical research director, UPSM’s department of emergency medicine.

Of the 481 patients in this study who had negative CT angiograms, meaning, no evidence of seriously blocked coronary arteries, none of these patients had heart attacks in the year following their exam, and none had bypass surgery or even stenting.

How much does an ER CT angiogram cost?

About $1,500. But admit a patient to the hospital for telemetry monitoring and stress tests?

You’re looking at over $4,000.

This often happens to patients who turn out not to have any serious coronary blockage, and could have been avoided with the quicker, much cheaper CT angiogram.

“The evidence now clearly shows that when used in appropriate patients in the ED, we can safely and rapidly reduce hospital admission and save money,” explains Dr. Hollander.

Perhaps a “national coverage decision” is just around the corner that will “facilitate coronary CTA in the emergency department,” adds Dr. Hollander.