The Benefits of Strength Training for Autistic Teenagers

Autistic teens need to spend less time playing videogames and more time strength training with weights – including girls.

Autistic Teen Girl Is Empowered by the Deadlift Exercise

Rylee was diagnosed autistic at seven.

She loves the deadlift exercise and explains how beneficial this is to her mental and emotional wellbeing.

Isaac Butterfield Doesn’t Understand Autism Spectrum Disorder

In a YouTube video Isaac Butterfield challenges why there are so many adult autism diagnoses these days.

Can You See a Brain Tumor from the Outside?

Is it at all possible to see a brain tumor from the outside of one’s head or even elsewhere?

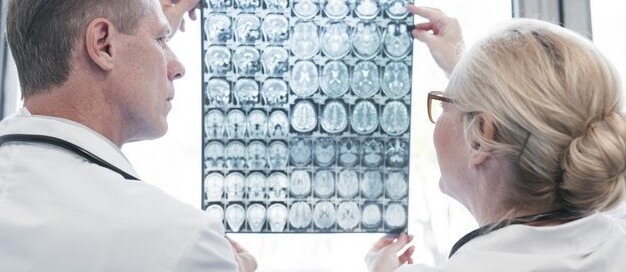

How Long a Brain Tumor Takes to Be Diagnosed in Adults

When a brain tumor shows on a scan, how much time usually passes before a doctor calls the patient?

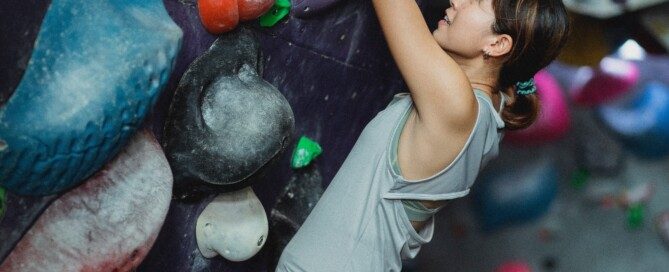

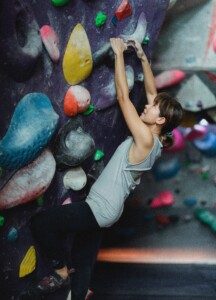

Five Reasons Autistic Kids Should Take up Bouldering

Bouldering is a form of climbing that can be done indoors at gyms dedicated to bouldering; no rope or harness required.

Autistic kids will benefit tremendously from bouldering. (more…)