Stage 1 esophageal cancer has a poor five-year survival rate, while that for other cancers (e.g., breast, prostate, melanoma) have a high survival rate.

For example, the five-year survival rate for regional – not just localized – prostate cancer is 100%.

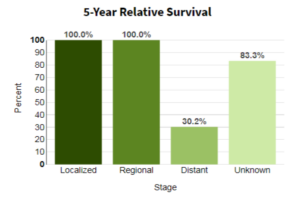

Check out the chart below from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance and Epidemiological End Results Program.

Prostate cancer survival rates

For localized colon cancer, it’s a bit over 90%. For breast it’s almost 99%.

Five-Year Survival Rate for Esophageal Cancer

And according to SEER, it’s 47%. This is poor. And to the layperson, it makes no sense because stage 1 is considered to be an early phase of a malignant tumor.

What’s going on here?

“It’s because EC spreads early and rapidly,” says Alex Little, MD, a thoracic surgeon with a special interest in esophageal and lung cancer.

But wait a minute – if it’s removed at the time of stage 1 diagnosis, it wouldn’t have time to rapidly spread, right?

Well, it’s not that simple.

Dr. Little explains, “Nearly all patients have spread to lymph nodes and/or distant organs when they first see a physician.

“Stage 1 disease (the tumor has not spread outside the esophagus, and there is no spread to lymph nodes or distant organs) is almost only found in patients with Barrett’s esophagus who have no symptoms and are receiving screening endoscopy.

“After an apparently successful esophagectomy with all evident cancer removed, including involved lymph nodes, recurrence is always in distant organs, showing they had occult metastases from the outset.”

These are “small and undetectable cancer cells — had already spread before the operation, and we can’t cure metastatic disease.”

So look at it this way. A local tumor is found in the esophagus. There is no detectable spread to the lymph nodes. The diagnosis is stage 1. Treatment follows.

But within five years, the cancer “returns” or “comes back” – and it’s in a distant site such as the brain or liver.

At this point, the patient is terminal. Most of these “recurrences” happen in the first few years; hence the low survival rate at the five-year mark.

The reason the terms return, comes back and recurrences are less-than-accurate is because the cancer cells were already present at the time of the stage 1 diagnosis.

Medical technology is not advanced enough to detect micro-metastases, or very tiny numbers of cancer cells, that have taken up real estate anywhere in the body.

For instance, the upper endoscopy will easily visualize the primary tumor in the esophagus.

But there could be literally a handful of metastasized cells in a lymph node.

By the time the patient’s treatment has concluded, the micro-mass in the lymph node has jumped in size, and some of it may have already broken off and traveled to another organ. Or, a year later, this could happen.

Or, at the time of stage 1 diagnosis and treatment, it’s possible that a micro-metastasis was already present in a kidney or the liver.

Within five years, that undetected mass will proliferate and spread more – sometimes not even causing any symptoms for a while.

And as Dr. Little had pointed out, there is no cure for metastatic disease of the esophagus.

A 10-year survival is exceedingly uncommon – so much so that it’s rarely discussed in the medical literature.

Higher Five-Year Survival Rates for Local Esophageal Cancer

If you research this enough, you’ll find varying survival rate ranges, going as high as over 80%.

However, you’ll also find that the range has a very low end as well: mid 40s.

Dr. Little explains that the higher end pertains to the “highly select and fortunate patients with limited enough disease that they are surgical candidates, who respond to preoperative radiation and/or chemotherapy, and are fit enough to tolerate an operation.

“This is a minority of patients.” Nearly every one of these patients’ tumors were discovered via their screening endoscopies for Barrett’s esophagus.

Alex Little, MD, trained in general and thoracic surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; has been active in national thoracic surgical societies as a speaker and participant, and served as president of the American College of Chest Physicians. He’s the author of “Cracking Chests: How Thoracic Surgery Got from Rocks to Sticks,” available on Amazon.

Alex Little, MD, trained in general and thoracic surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; has been active in national thoracic surgical societies as a speaker and participant, and served as president of the American College of Chest Physicians. He’s the author of “Cracking Chests: How Thoracic Surgery Got from Rocks to Sticks,” available on Amazon.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.