How come a stroke patient may recover lost speech, but nonverbal autistic people can’t learn to speak even though the same part of the brain is affected?

Not all stroke patients regain lost speech, but there are those who do make a remarkable recovery in this area with therapy.

- A stroke may render someone entirely speechless; no word can get out.

- In nonverbal autism, the individual, likewise, would be incapable of spoken language.

But sometimes the stroke sufferer talks again – meaning that something different is going on in their brain when compared to the autistic person, even though the same area of the brain is affected in both populations.

When people talk about stroke recovery versus nonspeaking autism, it helps to think of them like two completely different starting lines.

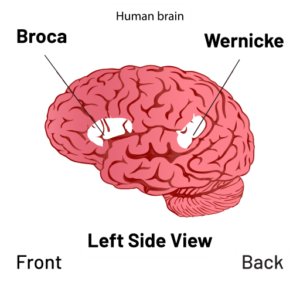

The headquarters in the brain for expressive language (talking, writing, typing, American Sign Language) is called Broca’s region or area.

Credit: UX Stalin

Suffering from a Stroke

When a stroke (either ischemic or hemorrhagic) causes loss of speech, this is called Broca’s aphasia. In this case, a previously intact speech network gets hit by an injury caused by either blood flow being cut off by a clot (ischemic) or a burst aneurysm causing bleeding (hemorrhagic).

The Broca’s area is located in the left frontal lobe of the brain, and part of that system stops working from the injury.

The brain’s job after that injury is to restore a skill it already knew: speaking.

Other regions can step in because the map of speech had already existed prior to the clot or bleed that damaged the brain tissue.

Think of it as taking the kind of old-fashioned road map, that people used when driving interstate, and crumpling it up.

It’s not usable this way. But you can uncrumple it and smooth it out, bending it in different directions to undo as much of the creasing as possible so that eventually, it’s usable again – though not perfect.

The Innate Wiring of Autism

Nonspeaking autism is nothing like having that map already there in the first place. In many autistic brains, the speech networks never developed typically to begin with; no “road map” for spoken language.

Thus, there’s no lost system to recover, to uncrumple and smooth out — no prior blueprint to restore.

The brain isn’t reorganizing after damage — because there is no damage; rather, it developed differently from the very start.

That’s the key: Neuroplasticity works best when it’s restoring something that once existed.

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to form new neural connections, typically when learning a skill or acquiring new information – or – reorganizing itself from an injury to regain a lost skill.

Speech never existed in nonverbal autism; there’s nothing to retrieve. Think of this as trying to make upgrades to a highway – a highway that had never been built in the first place.

Autism Is Not Damage — It’s Atypical Wiring

Something you’ll see again and again in autism research is that brains are wired differently, not damaged. Those in the autism community like to refer to this as a different operating system rather than a processing error.

A 2025 study led by Shinwon Park (Molecular Autism) found that the maturation of functional connectivity across different brain regions in autistics follows an atypical trajectory.

In simple narrative, the long highways that link frontal and temporal language centers often don’t stabilize the way they do in typical or non-autistic brains.

And the roads that do form (say, in autistics with partial speech) are sometimes just local loops rather than long-distance routes.

This would be why an autistic buddy of mine, “Kyle,” is totally unable to have a conversation and typically repeats the last several words that people say to him (echolalia), but in moments of high curiosity, interest or excitement, he’s capable of saying a complete sentence, such as, “That’s not good,” when I mentioned that a particular cat at the cat sanctuary didn’t like being held.

One day at the climbing gym Kyle suddenly blurted to a man with a cast on his leg, “What happened to your leg?” This took people by surprise.

So in nonverbal or semi-verbal autism, the brain isn’t missing speech — it never stabilized a typical speech network in the first place.

Speech Is More Than Language — It’s a Motor Act

Talking is a form of language, but not all language comes in the form of talking (e.g., ancient Egyptian symbols, American Sign Language).

Many nonverbal autistic people clearly understand language. This is called receptive language and occurs in a part of the brain called Wernicke’s area.

For example, I work with “Payzley,” who’s nonspeaking. I asked her if she brought a lunch from home.

Her response? Wordless but fully communicating the answer, she took her wallet from her purse, opened it and pulled out a $20 bill. This was a lot easier than the motor planning involved in saying “No.”

So in many cases, they have internal vocabulary (just how much is not known) and concepts. They get what’s said to them (though again, just how advanced this can get may never be known).

But producing spoken language requires a separate set of systems: that motor planning, plus timing and coordination.

Evidence shows that differences in speech motor pathways, not comprehension, can limit spoken output (O’Brien et al, NeuroImage: Clinical, 2022).

Other work shows that articulatory timing — the millisecond choreography of tongue, lips and jaw — differs in autism, affecting the rhythm and animation of speech in some individuals (Lau, et al, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2023).

If someone has never stabilized those motor speech programs, there’s nothing for the brain to recover as in the case of a stroke sufferer.

Why Reorganization Doesn’t Kick In the Same Way

Neuroplasticity depends on experience. To reorganize towards a skill, the brain usually needs three things:

- A target that once worked

- Repeated successful practice

- Reinforcement that strengthens the pathway

In autistics who can’t talk at all, attempts at speech can be noisy or fail altogether because the underlying motor program never stabilized.

The brain doesn’t get a clear reinforcement signal. So instead of reorganizing towards speech, it shifts towards what does work — gestures, AAC devices and an unmeasurable amount of internal language.

AAC stands for augmentative and alternative communication; these are iPads.

If there’s partial speaking ability, such as with Kyle, there’s a greater potential for typing answers to questions or expressing needs on a keyboard.

Kyle can open a note page on his phone and type brief answers to simple questions such as who his three favorite recording artists are.

What’s really odd is that, despite being able to read out loud fluently (this is neurologically easier than carrying on a conversation), navigate his phone, and speak the spontaneous short sentence, Kyle lacks the ability of back-and-forth texting no matter how basic.

He has a speech map already there, but – it’s partial. You can’t build onto it with material that doesn’t exist.

Why Some Remain Completely Mute

Some autistic individuals never develop any spoken language because their motor planning systems and sensory feedback loops are deeply atypical from early on.

Speech requires millisecond timing, fine motor control and continuous feedback correction.

If those systems were never wired to sync up, talking can be neurologically inaccessible, not just untrained.

This Is Not a Failure of Effort or Therapy

The brain of a stroke patient has the capacity to reorganize, to uncrumple a pre-existing map. The brain of a nonspeaking autistic is not failing to reorganize.

Their brains already have organization, just along a different developmental path. For non-talking autistics for whom speech therapy never produced any results, this isn’t a failure of the therapy.

You can’t train around a motor planning system that won’t reliably synchronize. It’s like trying to practice downhill skiing when you never had skis or a slope to begin with.

But you can buy skis and find a small slope, then build up to bigger ones, right? Well, what if you can’t buy the skis and there are no slopes?

The stroke patient already has a pair of skis and an accessible slope. It’s just that the skis now need repair, and the slope needs to be cleaned up.

Stroke recovery reorganizes around a previously existing skill. Nonspeaking autism reflects a brain that developed without that skill ever stabilizing.