Ever wonder why an autistic person who has no spoken language can’t just learn to sign the way deaf people do?

The reason behind this is nothing short of fascinating. It seems like a no-brainer: If an autistic child can’t speak, have them learn American Sign Language (ASL) – along with other family members so that everyone can communicate, the way people do when they learn their child is deaf.

Since my diagnosis of autism, I’ve met numerous of nonspeaking (complete lack of speech) autistic adults and a few teens at autism resource fairs, events for developmentally disabled adults, and as a direct support professional for a few agencies.

Based on my personal experiences, I’ve never encountered nonspeaking autistic individuals who also used ASL fluently or at a level similar to that of deaf individuals. In fact, I’ve never met any who even knew ASL at a most basic level.

Though my observation is anecdotal and not supported as a general conclusion by empirical research, it’s still tempting to believe that “severely” or “profoundly” autistic people without spoken language are not able to communicate via Amerian Sign Language (Howlin et al., Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2007).

Of course, most of these autistic adults have learned to use basic signals and gestures that would seem to come intuitively to anyone who can’t talk.

For example, they might hit their palm several times on a table to indicate, “Put my drawing right here.”

A nonverbal woman I work with curls her index finger to her thumb to signal she needs to use a restroom.

The Role of Intelligence

Sign languages are full languages on their own, with complex grammar and meaning, says research from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences.

Deaf individuals don’t just use American Sign Language to express basic needs; they communicate in complex ways to narrate their daily life experiences, describe their feelings, conduct business meetings and express anything else that hearing people normally do.

Why don’t we readily see autistic people, with no spoken language, doing this as well?

Some people might attribute this to a low IQ that happens to co-occur with the autism.

It’s easy to believe that when severe intellectual impairment is superimposed on a brain with autism, the result is absent spoken language – even though there are some non-autistic individuals with significant intellectual disability who can speak in full sentences.

Might the severe intellectual deficit also be what prevents learning ASL?

Though intellectual disability frequently occurs alongside autism (one does not cause the other), it’s often asserted that IQ plays no role in speech or sign language learning — a claim that remains insufficiently supported and oversimplified in the research literature (Bishop, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2010)

Why isn’t ASL common in nonverbal Autistics?

The area of the brain that enables speech via mouth is believed by many neuroscientists to be the same area that enables “speech” through the hands.

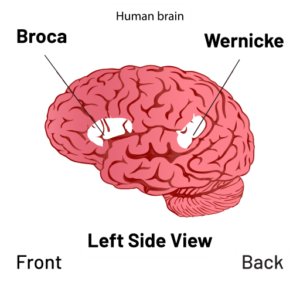

According to this, the intention to talk, even a single word, begins in a region of the brain called Broca’s area.

However, some scientists also believe that language intention and planning involve neural systems beyond Broca’s region (Fedorenko et al., Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2012).

If this area is normal, that intention gets converted to neuron signals that culminate in the physical output of that intention: full speech.

This same motor planning process seems to occur when the intention is to “talk” by using one’s arms, hands and fingers in ASL.

So if there’s a disruption (due to autism) in the expressive language motor planning that originates from Broca’s area, both speech and systematized sign language will be impaired.

Speech, ASL and Broca’s Area

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences wanted to know which brain regions are involved in processing sign language and how much these areas overlap with the regions used for spoken language.

They conducted a meta-study, combining data from sign language experiments around the world.

The study showed that Broca’s area was active in almost every sign language study they looked at.

How this Fascinating Study Was Done

The team compared the results of those sign language experiments with a huge database of brain scans from thousands of studies.

They confirmed that Broca’s area is used for both spoken and signed language.

These findings might be taken to mean that nonspeaking autistic individuals can’t learn ASL, even though neural overlap alone doesn’t necessarily demonstrate inability or causal limitation (Poldrack, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2011).

At the same time, we can’t ignore the difficulty in actually finding that autistic person — with no spoken language — using ASL fluently or even at a functional level (phrases, short comments, expressions of needs).

Intention to speak → motor planning sequence → physical output (speech, signing, writing, typing)

Broca’s Area As a Central Language Hub

The findings show that Broca’s area is the headquarters in the brain’s language network — but that doesn’t mean there aren’t neural networks beyond this area that are involved in language expression.

In fact, Broca’s works together with other networks depending on whether language comes in the form of signs, speech or writing.

Broca’s region handles abstract linguistic information in general, not just spoken language.

This makes it more understandable why an autistic person with impaired speech execution would also struggle with learning American Sign Language.

All in all, though, neuroscience is reluctant to confidently assert that impaired speech production in autism necessarily predicts difficulty learning ASL (Kasari et al., Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2013).

![]()