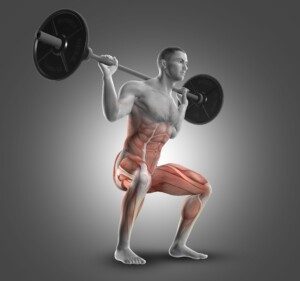

Being Tall Is No Excuse for Parallel Squat Problems!

Even a super tall NBA star could do an ass to grass squat if he has the right proportions!

Do not blame squat problems on being tall. Being tall, in and of itself, is not a disadvantage in performing a parallel or even deep back squat. The issue is not your overall height.

The issue is relative length of body segments!

It’s not an issue of getting long legs to bend under the body–UNLESS the torso is shorter than the femurs.

With “normal” proportions, those long legs will be under a proportionately long torso.

The proportionately long torso of the athlete will balance things out.

If you stand a 6-8 athlete next to a 5-8 athlete, who will have the longer legs? Obviously, the 6-8 person.

Now, who will have the longer torso? On average, the very tall athlete will have a much longer torso than the short guy.

Athletes do come in different proportions (anthropometrics), and these proportions influence efficacy of a particular weightlifting movement.

Ever see a champion in the deadlift who has T-rex arms?

Or how about a champion in the bench press with gorilla arms?

So what about the parallel squat? A tall individual can easily sink to parallel with an “upright” form as long as their femurs are shorter than their torso, and their shins are at least the length of their femurs.

Take notice of tall people’s femur to torso ratios. If you observe enough tall people, you’re bound to eventually spot some with “stubby” femurs.

They’ll have an easy time squatting (assuming they don’t have a history of back pain).

If distance from hip to knee is shorter than distance from clavicle to waist, they’ll have no problem back squatting.

Short stature is not necessarily an advantage in squatting.

It absolutely is not if one’s femurs are longer than their torso.

Remember, while a tall person has the long legs in the absolute sense, you must look at these legs within the context of the rest of their physique.

I’ve seen 6-4 men with gorilla builds and short people who were “all legs” and had the torsos of a person half a foot shorter.

Being very tall, in and of itself, “ain’t no excuse” for having trouble squatting.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Freepik/freepic.diller

Can Femur to Shin Length Ratio Affect the Back Squat?

It isn’t just femur to torso ratio that can create problems with the back squat; shin length relative to upper leg can also mess things up.

You’re aware that if the femurs are longer than the torso, this will make the back squat difficult, sometimes very difficult, for an individual.

Let’s not dismiss the impact that shin length (tibia bone) can have on the squat, especially the back version.

Though I used to be a personal trainer and was keenly aware of body segment proportions of my clients, one need not be an exercise instructor to see some obvious points.

How does shin or tibia length influence the ability to sink to parallel in the back squat without excessive torso lean?

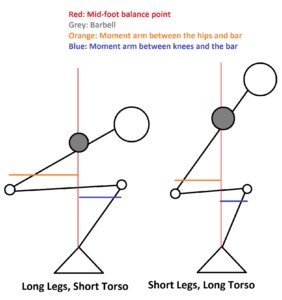

Certainly you know that to keep balance, one must keep the barbell over the ankle: a vertical point-to-point alignment.

The longer one’s femurs are without the length of the torso changing, the farther their butt is from their knees, and the more bent their torso is (a smaller angle formed by femurs and torso).

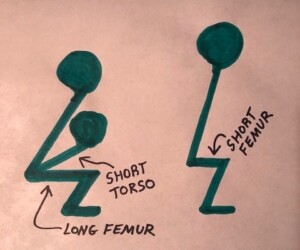

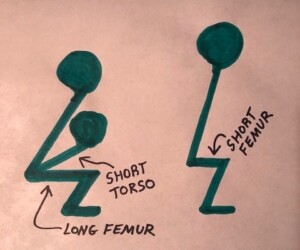

To make it easy to understand how tibia or shin length can play a role, look at the illustration below.

It’s hard to imagine the stick figure on the right falling backwards with all that tibia supporting him like a pedestal. Now, shrink the tibia to a centimeter. What happens?

Look at the figure on the left. That short (relatively) tibia has a lot of body to support.

The longer one’s shin bone, the easier it is to get the foot vertically aligned with the shoulder without having to pitch the torso way forward.

This isn’t only about ankle flexibility.

An extra inch of tibia in a person, for whom nothing else changes, will place their ankles back by about an inch, and allow that person to subtract an inch off their forward lean.

An extra inch of tibia sets the foot back about one inch, assuming that all other proportions remain the same.

The following is an excerpt from the book, “Scrawny to Brawny; The Complete Guide to Building Muscle the Natural Way,” by Michael Mejia and John Berardi, PhD.:

A femur that’s longer than your torso can compromise your ability to squat and deadlift efficiently because it will cause you to lean forward excessively to reach the desired depth.

Of course, a femur and torso of near equal length combined with a shorter lower leg can sometimes pose similar problems, although this can often be effectively managed by improving flexibility around the ankle joint.

The “lower leg” of course refers to the tibia or shin. Improving ankle flexibility allows a person to shift the knees more forward, thereby shifting the barbell more overhead of the ankle.

If you’ve been struggling with the back squat, it may not be so much that you have “long femurs,” but rather, short shins.

Everything else looks in proportion, and then you get to your short tibias.

Moving the kneecaps up a few inches would make your body look more proportionate.

Long femurs do get a bad rap, but sometimes the tibia should get some of the blame.

Often, though, a person’s tibia is the same length as their femur, but their torso is shorter than their femur, making them struggle with the back squat.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

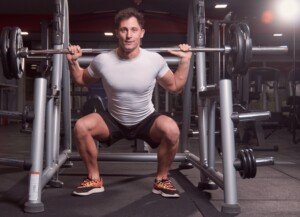

Top image: Shutterstock/UfaBizPhoto

Source: enotalone.com/health/4855.html

Why Elevated Heels Make Squatting to Parallel Easier

Anyone who’s struggled to get parallel in the squat (femur torso ratio) knows that elevating the heels makes this possible, and here’s why.

For those with long femurs and short torso who can’t achieve a parallel squat without leaning over like in a “good morning” position, elevating the heels (even a little bit) makes getting parallel possible.

If you’ve elevated your heels to get into a parallel squat (due to torso shorter than femur), perhaps you’ve also noticed that it seems as though more tension is on the knees and middle muscle of the thigh. You are not imagining this.

Why does elevating the heels make it possible to parallel squat in those with long femurs and short torsos?

In order to keep balance and prevent falling backwards while descending towards parallel, you must keep the shoulder aligned vertically with the midfoot.

One way to get the shoulder over the midfoot is to lean the torso forward.

Long femurs force the hips out further when lowering into a parallel squat, which means that the torso has more distance to lean forward to get the shoulders over the midfoot.

Those with long torsos don’t have as far to go as those with short torsos, assuming that relative femur length is identical for both people.

Sometimes the femurs are the bigger culprits, in that they are much longer than the shin bones.

The other way to get the shoulder aligned with the midfoot is to shift the knees forward while keeping the feet flat on the floor.

Shifting the knees forward will, in turn, shift the shoulders forward, while the feet stay fixed in one spot on the ground.

Your knees will shift forward (keeping heels on floor) only as far as the flexibility in your heel/foot will allow (a joint action called dorsiflexion).

If you go up on the balls of your feet, which elevates your heel, you can squat parallel and even all the way down while keeping a straight back.

- The elevated heel rotates the position of the feet forward, or “tips” them forward.

- This tipping automatically pushes the knees out more.

- Your shoulder is now easily aligned over your midfoot without having to lean the torso forward.

HOWEVER, you’ll also notice that when squatting on the balls of your feet, which produces a considerable ankle elevation, the knees may feel strained.

Squat all the way down (like a baseball catcher), then stand all the way up — on the balls of your feet. Feel that in the knees? And do you feel it in the middle quad muscle?

This is because the knees were way ahead of the feet, which is a poor way to perform a barbell or even goblet squat.

Now, imagine placing the heels on a one-inch-high board, a few small weight plates to elevate them, or elevating the heels by wearing a heeled shoe.

You can now more comfortably squat parallel despite the long femurs and short torso.

Again, the elevation “tips” the foot forward, which automatically drives the knees out further in front.

This forward shift causes the shoulders to forward shift, bringing them in alignment with the midfoot.

Unfortunately, as just pointed out, this forward shift puts more tension on the knees and subtracts tension from the glutes and hamstrings.

Nevertheless, the slight heel elevation is a sensible option for those with long femurs and a short torso who struggle to parallel squat.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Top image: Shutterstock/coka

Does Sitting, Rising from Chair Mean You Can Parallel Squat?

I could not believe it when a strength training enthusiast chastised another about the parallel squat, in that the one trainee insisted he was not able to squat due to a short torso (and long femurs).

The critical person said, “If you can get up and down from a chair and toilet, you can do a parallel squat, so stop making excuses!”

People with short torsos and long femurs can get into a parallel squat. Few people will deny this.

However, the position your body takes, when sitting onto a toilet and then rising, is not the recommended or same position that one should perform a barbell squat with!

Using a toilet involves crouching forward, supporting oneself with the forearms on the thighs! Who sits upright, arms off thighs, with a lower back arch while on a toilet?

And what fitness expert or even experienced trainee would recommend barbell squatting with a crouched forward torso?

The crouched forward torso makes it easy as pie to rise from a toilet!

As for lowering and rising from a chair, this comparison to the parallel squat is deeply flawed because the chair prevents a person from falling backwards onto the floor!

Who squats parallel with a barbell or even bodyweight only, with their legs, feet and back positioned as they are when getting into and out of a standard chair?

Last time I checked, not a single human being on this planet. It is physically impossible.

Getting into and out of a chair does not require the ankle dorsiflexion that a parallel squat does.

The chair provides external support, too. In a parallel squat for exercise, nothing supports the trainee!

Of Short Torsos and Long Femurs…

Though a chair is an excellent training tool for developing a parallel squat for those with short torsos and long femurs, getting into and out of a chair in daily life is an extremely poor analogy to the parallel squat!

Those with short torsos and long femurs can hover over a chair and practice the lower back arch and minimizing the forward torso lean, and experiment with dorsiflexion while viewing their profile in a mirror.

To say that getting into and out of a chair or onto and off a toilet means that you can parallel squat, means that your 87-year-old Grandma can parallel squat because she can lower and rise from a dining room chair and get onto and off a toilet without assistance!

Can you picture Grandma squatting to parallel without holding onto anything, let alone with a barbell across her back?

The muscular forces and leverages that a parallel squat requires are NOT required to lower into a chair and then stand up from it.

This is why when a person lowers into a chair and a sneaky person pulls the chair out from under them, they fall flat on their can instead of remaining suspended in the air in a parallel squat position, even when they know what just happened!

I said earlier that those with short torsos and long femurs can get into a parallel squat.

BUT — the problem is, if their femur, shin bone and torso ratios are disadvantaged enough, they will need to execute a severe forward torso lean, making the lower back arch impossible.

Their back is rounded, chest smack on top of their thighs (think of a closed clam shell or a speed skater cruising in a distance race).

Often, to hold even THIS position, those with short torsos and long femurs must have their arms straight out in front of them.

So how is it possible for these trainees to execute a parallel squat with their back erect enough to support a barbell without rounding their back?

Those with short torsos and long femurs can have all the ankle, hip and low back flexibility in the world, and still find it impossible to avoid the rounded, slumped-over back while going parallel.

Their only recourse is to Sumo their stance or elevate their heels, best done with shoe lifts, which are significantly cheaper than weightlifting shoes.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: brusblaus/CC

Yes, TALL People CAN Have Short Femurs

Super tall men with relatively short femurs have a squat advantage over shorties with relatively long femurs ANY DAY.

Many believe that being tall interferes with doing a parallel squat because, allegedly, it’s troublesome to get long legs bent under one’s upper body.

But with long legs comes a longer trunk (because in tall people, everything is longer) to help offset the tendency to “fall backwards” while doing a squat.

A typical 6-4 man has a longer torso than a typical 5-4 man.

If someone stands 5-10 and has legs as long as the average 6-4 person, there will be a big problem with squatting parallel, because the torso for this person is too short to offset femur length.

Likewise, take those same legs; put them on someone with a torso long enough to put them at 6-8, and we now have a nice combination for the parallel squat … unless the femurs are super-crazy long in relation to the shin length.

Tall people can have short femurs.

How is it that in strongman competitions these very tall guys are squatting thunderous amounts of weight?

Look at their femurs! Their thigh bones are NOT relatively long (compared to shin length). Many appear rather “stubby.”

Another venue where short femurs on tall people are evident is in the world of runway modeling and in the models in glamour magazines.

Models are tall, many being 5-10 and 5-11. Google leg images for your favorite tall movie star and look at her femurs; some will be relatively short.

Tall People and the Parallel Squat

So when I hear tall people announcing, “I can’t squat parallel because I’m tall,” I really wonder.

The proportions in this illustration can be seen in tall men. Look around at your gym. I’ve seen tall men with femur lengths almost half their torso. Freepik.com/kjpargeter

The parallel squat can be very difficult for a SHORT person with relatively long femurs to shin ratio (or to torso length).

The body build that is often not built for squatting is that of the elite marathon runner.

They rarely have relatively short femurs and often have high waists (short torsos), which helps reduce drag when running.

The long femur and short torso duo is a wicked combination for parallel back squats. A 5-2 person can have this anthropometry.

A very tall person can have short femurs (relative to shin length and/or torso length), making them well-built for the parallel squat.

An important point is that many competitive Olympic-style weightlifters, who do well in competition, are tall.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Shutterstock/SeaRick1

Do Long Femurs and a Bad Squat Mean You’re Weak?

If you’re biomechanically disadvantaged due to femurs that are longer than your torso, find out if this means you’re weak.

When a person with long femurs (meaning, femurs longer than their torso, regardless of overall body height) tries the back squat for the first time, even with just body weight, they immediately realize there’s a problem.

If you clicked on this article, then you already know what the issue is with long femurs and the squat.

You also certainly have come across the term “biomechanical disadvantage,” and perhaps have read quite a bit of content in fitness forums saying that those with long femurs and a short torso can injure themselves doing heavy back squats, and even that they should avoid this exercise altogether.

In short (no pun intended), it’s almost as though having long femurs and a short torso is a disability that makes people weak.

In the truest sense of the meaning of “weak,” a person with this anthropometry is NOT weak. They can be very strong.

The issue isn’t strength per se. It’s body position.

Let’s take a really strong beast of a person as an example, say, an Olympic heavyweight weightlifter. Now, let’s lie him on his back.

Though this is an extreme example, its extremeness will clearly illustrate why the person with the long femurs and short torso is not weak, but instead, it’s an issue of body position — a body position that he or she cannot access.

So we have this very strong person lying on the ground on his back. Beside him on the ground is a 50 pound kettlebell that he can reach only by straightening his arm.

His job is to lift the weight off the ground — while maintaining his position of back lying on the ground.

This means he must grab the weight with a straight arm, and because his back must stay on the ground, he cannot bend his arm.

Though he has brute strength (remember, he’s on the Olympic weightlifting team), he will not be able to lift the kettlebell.

Does this mean he’s weak?

Or does it mean he’s at a biomechanical disadvantage due to body positioning?

Because he’s not able to get into an efficient lifting position, he is not able to move the weight. It’s a matter of body position, not lack of muscle strength.

Again, this example is extreme, but you can apply a scaled-down version of this principle to the individual with the long femurs and short torso.

They are simply not able to get into an upright squat position, and thus, are not able to utilize the strongest muscles of their body to squat heavy weight.

Instead, their lower back muscles (which are not force production muscles by nature) are made to take some of the weight.

The deeper this person gets into the squat, the more he must lean forward to keep from falling backwards.

Somehow, someway, famed powerlifter Lane Norton pulls this off with a ton of weight, despite having “bad levers” — femurs long relative to torso length:

If this forward lean is severe enough, it becomes impossible for most people to maintain an arch in the lower back, and the back rounds, creating the potential for disaster.

The person ends up “lifting with their back” instead of “lifting with their legs.”

This is a very inefficient way to lift heavy weight, but it occurs due to the long femur short torso person being unable to get into the position of upright back while squatting (they are leaned way over). Literally, their long femurs get in the way of the lift.

Now take a look at the femur to torso ratio of the man below. His squat is almost as deep as Norton’s, but check out his ridiculously upright back!

The biomechanical rather than strength issue isn’t just present when trying to squat with a barbell across the upper back.

The long femurs get in the way when picking something heavy off the ground as well (you name it: big potted plant, crate of books, file cabinet, big sick dog).

The individual with this anthropometry has two choices: 1) Squat half-way but lean far over (risking low back injury) to get their hands between the object and the ground, or

2) Squat nearly all the way to keep their back upright while holding onto the object to prevent falling backwards, and while in this position, lifting the object.

The problem with #2, even though the back is upright, is that the heavy lift begins from a deep squat, which is harder than a heavy lift from a half-way squat.

A person whose femurs are shorter than their torso can maintain an upright back as they descend into the squat, and thus can begin lifting the heavy object when they’ve reached half-squat depth — less range of motion to do the lift!

So you see, long femurs and a short torso do not make a person weak; they just prevent that person from getting into the most efficient body position to perform a lift.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Freepik.com

Causes of the Butt Wink in Back Squatting

It’s a myth that the squat butt wink is caused ONLY by tight hamstrings or tight hips!

Want to know what really is behind the cause of the butt wink motion that so many people do when performing the back squat?

The answer is really quite simple: The trainee fails to maintain a straight back.

But then, that begs the next question: Why do people fail to keep a straight back when performing this version of the squat?

I have a second explanation for the butt wink, though this second explanation may, at least in part, explain why a person fails to keep their back straight as they begin closing in on depth. And that’s “bad levers.”

Though not all people who commit the butt wink have relatively long femurs (or femur bones longer than their torso), it’s a fact that long femurs (relative to torso length, regardless of one’s total body height) predispose a person to the butt wink problem.

But as just mentioned, this may all point back to why a person fails to keep their back straight.

When I say straight, I don’t mean vertical, but rather, not rounded or hunched — but having an arch in the lower back, as shown below.

Freepik

The butt wink is the opposite of the arch; the lower back rounds out or loses its extension; it becomes flexed.

Tight hamstrings are often blamed as the cause of the butt wink.

I do not have tight hamstrings, yet if I get low enough with the back squat, I’ll butt wink.

I can’t say with 100 percent certainty that this is caused by the fact that my femurs are relatively long compared to my torso, but I can definitely rule out BOTH tight hamstrings and tight hips. I have good hip flexibility!

However, I can hit just below parallel before the butt wink starts in.

But still, if I’m nearly ATG, a slight butt wink is present, and has absolutely nothing to do with my hamstrings, hips or ankle mobility.

A butt wink will occur in anyone if they go low enough in a wall squat, in combination with their feet being close enough together, toes pointed straight ahead.

In other words, a person with short femurs, long torso, rubber-band-like hamstrings and hips, will produce a butt wink if they’re right up against the wall, feet less than shoulder width apart (or even at shoulder width), and sink ATG.

Often, the butt wink is caused simply by lack of concentration. Once a person is aware of it, it can sometimes be instantly or near-instantly corrected.

Other individuals will need to practice, and sufficient practice may eliminate the problem.

Poor squat form with the legs can also cause it. Have a qualified partner or personal trainer watch you; trying to watch yourself as you squat is not a practical way to practice this exercise.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Shutterstock/HD92

Can Short People Have Relatively Long Femurs ?

Short people CAN have a relatively long femur, meaning, their thigh bone is longer than their torso — even if their overall height is way shorter than average.

As a former personal trainer, I am fascinated by the anthropometrics of long femurs as this relates to the squat and deadlift exercises, but am puzzled that so many people believe that only tall people can have long femurs that sabotage squatting.

John Kagwe, long-distance runner, 5’6″

Of course, a 6-4 person has a long thigh bone in the absolute sense, but not necessarily in the relative sense.

When it comes to the squat (or deadlift), relative length is the factor, as in length of femur relative to shin bone.

What about short people?

A short person can have a noticeably long femur relative to his or her shin bone length.

If you take notice of enough people in shorts or leggings, you’ll sooner or later come upon a short person whose femurs are disproportionately long for either their torso or their shins.

Now check out the thigh bones of very tall people, RELATIVE to their shins!

Some of them have noticeably short femurs (and thus, lengthy shins).

Being tall does not necessarily screw up your ability to squat or deadlift.

This is clearly evident in strongman competitions, in which athletes of towering height deadlift enormous amounts of weight.

You’ll also see tall people at powerlifting events as well, performing amazing deadlifts and squats.

- With the tall person’s longer thigh bone (in the absolute sense!), also comes a longer shin and longer torso to go with it.

- And the longer shin and longer torso balance things out.

A short athlete can have a femur that’s longer than his or her torso, making the parallel squat more challenging.

If you still believe that short men or women can’t have relatively long femurs, then take some notice of thigh length — relative to overall height — of short adults whenever you’re out and about, especially at crowded venues (amusement parks, shopping centers, festivals, etc.).

You may even spot a “long-femured short person” at your own gym, while also catching sight of men well over six feet who clearly have thighs that are much shorter than their torsos.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Freepik.com

Sources:

hbing.com/images/search?q=john+kagwe&view=detail&id=CF6FCC3F646FF5DD15FD95A46BB17B0949615210 ninamatsumoto.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/athletes05.jpg

forum.bodybuilding.com/showthread.php?t=138030823&page=1

Can Long Femurs Be a Disadvantage in Daily Life?

You know that long femurs are a curse for squatting exercises, but does this problem carry over to day-to-day activities?

As a former personal trainer and always-fitness enthusiast, this topic intrigues me.

If you clicked on this article you probably have long femurs (and a short torso) and struggle with the squat exercise.

But have you wondered just how much this anthropometry affects daily activities?

The long femurs and short torso body type, indeed, moves differently in real life.

But because real life movements aren’t the same as the back squat, people whose femurs are longer than their torso will not necessarily make a connection between why they must move a certain way, and their body proportions.

When trying to barbell squat, the person whose femurs are longer than their torso will know there’s a big problem.

That’s because it’s impossible not to notice that if you don’t lean your torso far forward in a barbell back squat, you’ll fall backwards.

In real life, the issue of falling backwards gets unnoticed because when a person with long femurs and short torso bends their legs to pick a heavy item off the floor — their hands on the object, or arms wrapped around it — prevents them from feeling the sensation that they’ll fall backwards.

Shutterstock/studioloco

They simply bend over, grab the item and lift it. In a barbell squat, you are not grabbing onto anything for support, so the tendency to fall backwards is glaringly obvious.

The exerciser is thus forced to think about limb proportions and biomechanics.

So if a person with long femurs and a short torso can, indeed, pick a heavy object off the ground, how is he or she affected by their anti-gym squat anthropometry?

It’s a matter of degree of range of motion.

Let’s take two people of equal height and weight, Mark and Rip.

Mark’s femurs are a lot shorter than his long torso. Rip’s femurs are a lot longer than his short torso.

However, both guys train hard and are strong. There are 10 heavy crates on the ground. About midway down on either side of each crate is a handle.

The proper way to pick them up is to squat (feet FLAT on ground), keeping the back upright, grab the handles and “lift with the legs.”

To make this easier to understand, imagine that Mark’s femurs are six inches long and his torso is two feet long.

He only needs to squat half-way (thighs parallel to ground) to reach the crate handles while still in an upright position.

His lift, then, consists of coming out of a HALF squat.

Imagine that Rip’s femurs are two feet long and his torso is one foot long.

Rip will fall backwards long before his squat gets half-way unless he bends his torso to practically parallel with outstretched arms.

He can also grab the top of the crate. However, this puts him in a position that makes it impossible to pick up the crate.

In order to lift it, his groin must be close to the crate. (Did you not picture this with Mark?)

If Rip simply leans over and grabs the handles, what happens to his body? He’s nowhere near a half-squat.

His torso is bent so far over that it’s well-below parallel and his back is totally rounded, butt poking high into the air.

He can pick the crate up this way, but it puts tremendous stress on his lower back!

If he tries to squat parallel while holding the handles, his long femurs get in the way; he can’t do it.

In order to keep his hands on the crate WHILE being in a parallel squat, he must distance his body from the crate, making it impossible to lift it.

The person with long femurs and a short torso has two choices.

He can either lift the crate from the position of being stooped way over (torso well-below parallel, back rounded, legs nowhere near a half-squat, butt sticking up into the air), OR —

He can get into a full “ATG” squat. This will enable him to be close enough to the box to get his hands on the handles, while keeping his back much more upright.

The illustration below will help you understand the general concept.

Who’s in a better position to lift that crate with their hands (assuming both have equal length arms)? The body on the left or right?

Close your eyes and visualize a man with super long femurs in a full squat, back upright, arms out in front holding onto the crate handles for balance.

Unless Rip has arthritic knees, this position is easily doable. Of course, the second he lets go of the handles, he’ll fall flat on his back.

To lift the crate, Rip rises from a full squat, straight up, back upright. The lift consists of a FULL squat.

- Mark picks up 10 crates; that’s 10 half-squats.

- Rip picks up 10 crates; that’s 10 FULL squats.

Rip must do more work! The same scenario occurs when they must set the crates down; Mark gets to do 10 half-squats, but Rip must do 10 FULL squats!

Though Rip may have stronger muscles than Mark, his inability to get into an efficient body position causes him to fatigue faster than Mark; the job is harder.

In summary, those with femurs longer than their torsos must perform full or three-quarter squats (depending on height of object to be picked up), to lift something off the ground with an upright back.

However, those with the opposite proportions get to do only half-squats.

And if the long femur person wants to do a half-squat, he has to forfeit the upright back!

There’s a third option for those with long femurs and a short torso: a wide stance with feet pointed out; this will enable a more upright back.

There’s a caveat: This shifts some work to the weaker adductor muscles (inner thigh).

Nevertheless, those with long femurs and a short torso can train hard and develop a very strong wide or “sumo” stance.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Freepik.com

Best Way to Tell if Femurs Are Too Long for Back Squat

There’s a fool proof way to tell if your femurs are too long for decent parallel back squats.

If you can’t parallel squat, does this automatically mean your femurs are too long relative to the rest of your body, or is there a way to accurately determine this since other variables can prevent a parallel squat?

I’m a former certified personal trainer and have plenty of experience with relatively long femurs.

Some frustrated clients have asked, “How can I tell if my femurs are too long?” It’s easy to tell these trainees to just look at their legs.

If the thighs look out of proportion in terms of being too long, then you probably have long femurs.

However, what one person might think is too long, another person (who has long femurs) might think is normal.

Almost every anatomical illustration I’ve ever seen depicts the femurs as too long for the rest of the legs (in my opinion, anyways). The shins in anatomical illustrations are usually puny.

Another way people try to evaluate femur length is with a tape measure. The problem here is two-pronged:

1) Exactly where are the measuring points? And

2) For people of generous girth, it will be difficult to locate the hip bone.

Fool proof way to determine if long femurs are hampering your back squat.

And as you may already know, if a person’s torso is longer than their femurs, this can help offset problems with the back squat, even if their femurs are disproportionately long for their legs.

The best way to tell if long femurs are your problem (as well as a short torso) is to find a chair, bench or stool that — when you sit on it, your thighs are perfectly parallel to the floor.

If they are not parallel (meaning, the hips are higher OR lower than the knees), this test won’t be fool proof.

Next, make sure you’re sitting before a mirror, profile facing it. It’s mandatory that you be able to readily view your profile.

If you’re on a chair, sit off of it somewhat to give your calves room to move.

If you’re wearing the shoes that you normally squat in, that’s fine, but for optimal accuracy, do this test barefoot.

At all times during this test, keep feet flat on floor.

Place feet about shoulder width apart, toes pointed ahead.

Place feet so that knees are ahead of them as in a back squat, but keep heels on floor.

Viewing your profile, start leaning forward and maintain an arch in your lower back, as you would during a squat. Do not round your back.

The objective is to form a vertical line between your ankle and the back of your shoulder.

The back of your shoulder is where a barbell would be for the squat.

How far must you lean forward to create a vertical line between your ankle and the back of your shoulder?

In other words, the back of your shoulder (picture a barbell there) perfectly aligns, or is directly overhead, your ankle.

Are you REALLY far over, to the point where you’ve lost that lower back arch?

Is your torso virtually parallel to the floor?

Do you feel your back rounding?

If these points describe you, you have “long femurs.”

But don’t give up yet; see if you can move your knees further ahead of your feet: Shift forward on the seat WITHOUT your feet moving a millimeter.

Is there room to get those knees out a little bit more?

If so, this will allow you to retract a little bit on the forward torso lean.

Below is a wide stance squat. Note how it allows the athlete’s back to be remarkably upright.

Shutterstock/Veles Studio

Nevertheless, these aforementioned issues spell long femurs.

Again, widening the stance will allow you to retract on the forward torso lean.

Two Points to Consider

1) Being very leaned forward puts strain on the lower back and forces the lower back to absorb some of the forces from the squatting movement, and

2) A pronounced dorsiflexion of the feet (caused by moving the knees forward as much as possible) diverts some work away from the hamstrings and glutes, and concentrates more of it on the middle quad muscle as well as the knee joint.

Anyone who knows the basics about the back squat knows that these biomechanics stink.

Yet there are those who insist that the long femur is a lame excuse for lazy people.

The ideal back squat biomechanics have the spinal column in an almost upright position, eliminating low spinal strain, and dorsiflexion is minimal, allowing maximal workload to be absorbed by the body’s three most powerful muscle groups:

GLUTES, HAMSTRINGS, QUADS

This is the recipe for maximal lifts in the back squat with minimal risk of knee joint and low spinal strain.

This test also clearly demonstrates why a short torso is a potential curse in the back squat.

I say potential because if you have really short femurs, they can somewhat offset the short torso.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.