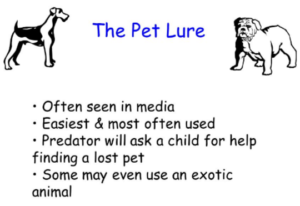

Have you drilled your child about the lost puppy ruse that predators often use to lure children into harm’s way? You can easily teach your child not to fall for this ploy.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children studied the attempted abductions of 7,000 children between Feb. 2005 and Jan. 2012. Eight percent of the suspects who were identified and arrested used the lost puppy (or cat) lure.

Your warning of, “If an adult ever asks you to help him look for his lost puppy, RUN!” may seem sufficient to you, but may be terribly inadequate for a child.

“It is vital that parents teach their children how to identify danger and what to do in different dangerous scenarios,” says Talia Wagner, a Los Angeles based marriage and family therapist.

“Explain to your child that adults use this as a lure to entrap and harm them,” says Robert Siciliano, CEO of Safr.Me.com and an expert in fraud prevention and personal safety.

“Explain to children that adults do not ever, for any reason, no matter how much they persist, need the help of a child, generally to find a puppy or anything else for that matter.”

How to Teach Child about the Lost Puppy Lure

Ask your child the open-end question: “What would you think if an adult stranger approached you and asked him to help him look for his lost puppy?” This will get him thinking.

If he says he’d realize that this stranger meant danger, ask him to explain why. This will further build up his stranger-danger radar.

If your child says she’d help him look for his lost pet, here’s your game plan:

#1. Ask your child, “If you lost your puppy, who would you want to help you look for it — a child your age, or a grown-up?” Your kid will invariably answer, “a grown-up.”

#2. Ask him why he’d prefer an adult to help him with the search. Then listen. Any number of reasons will surface, such as:

- “Adults are taller and can see better”

- “Adults can drive cars and we could search faster,” and

- “Adults are smarter.” The act of thinking out these reasons will strengthen a child’s stranger-danger radar.

#3. Ask her if it would make ANY sense at all, for an adult to ask a child her age to help look for a lost dog.

Your kid will reflect upon this, and then inevitably say something like, “I can’t drive so I wouldn’t be able to help much,” or, “I’m too little to see down the street.”

This will drill it into her head that, indeed, no stranger would want a child’s help in searching for something when there are adults around who can help. This realization will further reinforce your child’s stranger-danger radar.

#4. Ask your kid how much help he could possibly be, if he rides in a car with the stranger, looking for the dog.

Say, “What can you do, sitting in the car, barely able to see over the dashboard, that the adult who’s driving the car CAN’T do?” Then listen.

Then ask, “Even if you CAN see over the dash or out the side window, what are you going to see that the much bigger driver can’t see himself?” Then listen.

#5. Ask, “Don’t you think that if someone truthfully wanted you to look on foot for their lost dog, they’d want you to go in one direction while they went in the opposite, so that a bigger search area is covered?” Then listen.

#6. Top it off with: “If YOU wanted someone to help you look for a prized possession, how much help could they be if they stuck by your side, rather than went off in another direction?

So if an adult wants you to come with him to help search for his lost puppy, what does that tell you?”

At this point, a child should have a much more advanced understanding of this ruse. The older a child, the more they will “get it.”

“Parents need to talk to their children about these dangers, teaching them what different forms danger could take,” says Wagner.

“It is important that you have this conversation and have it often.” She also recommends role-playing, not just discussing.

Don’t start this discussion while driving your child to soccer practice or while waiting in a long line at the supermarket.

This discussion should be carried out in a setting where there’s no time crunch, and where there’s no distractions.

Wagner also adds that these tactics will be less effective with very young children who naturally lack the logic that these tactics draw upon.

However, unfortunately, kids as old as 12, absent stranger-safety training, can easily be lured by the lost puppy ruse.

One final note: A savvy predator will tell a child that his dog answers only to the voice of young children.

Have your child write 50 times, “Dogs do not only answer to kids’ voices.” Tell him after he completes this “project,” you will play with him his favorite game.

So that this project doesn’t seem like a chore, use different colored construction paper, color markers, and encourage your child to decorate the paper with glitter, star stickers, etc.

Don’t assume your child will recognize the lost puppy lure simply because you spent 30 seconds pointing it out. Kids need drills, training and role-playing.

Talia Wagner, along with her husband Allen, has a private practice in California.

Talia Wagner, along with her husband Allen, has a private practice in California.

Robert Siciliano is a private investigator fiercely committed to informing, educating and empowering people to protect themselves and their loved-ones from violence and crime — both in their physical and virtual interactions.

Robert Siciliano is a private investigator fiercely committed to informing, educating and empowering people to protect themselves and their loved-ones from violence and crime — both in their physical and virtual interactions.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.