The most striking thing about keratoconus and the apparently other congenital eye diseases that greeted me upon, or relatively shortly thereafter, my birth (i.e., amblyopia, alternating vision), is that I’ve never known what it is like to have “normal vision.”

Shortly after I was born, I underwent surgery to correct my “crossed eyes.”

My first memory of what passed for vision screening nearly seven decades ago was of having each eye covered while I tilted my hand in the direction of the letter “E” as I read it, first with one eye covered, then the other, on a screen.

Right-side up, upside down, flipped left, then right — that was my introduction to the fifth letter of the alphabet, thanks to the ophthalmologist who felt it necessary to examine me at a time when most everyone else I knew could get by with an optometrist’s appointment (though, at that age I was probably only familiar with the generic term “eye doctor”).

I was fitted with my first pair of glasses at age three. As a toddler I developed amblyopia, leaving me with vivid memories of the pirate patch I wore in order to correct my “lazy eye.”

There must have been some other kids who wore glasses, but I don’t remember any.

All I remember was being teased and being treated like an outcast at a time I wanted to fit in.

Growing up in Minnesota within walking distance of two elementary schools, as I walked to and from Fern Hill (and later Park Hill) school, during a Gopher state winter, I always looked forward to spring when my glasses would no longer fog up.

I also had to endure the memorable indignity of a bully breaking my glasses.

As my vision worsened, my annual eye care appointments became semiannual, but hope was on the horizon when I became a teenager. It was then that I first became aware of the term kerataconus.

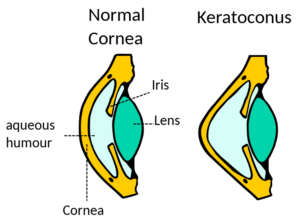

Keratoconus is a thinning of the cornea. Vision is sometimes blurry, and nighttime driving distorts the way headlights and taillights appear.

Keratoconus develops slowly but, in my case, definitively during my early teens to the point where, following associated eye surgery, little-by-little I was able to reduce the time I wore glasses and wear the then-fashionably trendy hard contact lenses for increasing periods of time!

Though there was (and over a half-century later remains) no cure for keratoconus, contact lenses not only have a stabilizing effect, they improve the quality of vision of glasses alone.

Though keratoconus prevented me from wearing soft contact lenses, as the technology improved, I was able to graduate to gas permeable contact lenses.

But, as my keratoconus eventually progressed, even gas permeable lenses failed me, as the shape of my corneas — never fully round like most people’s — became so pointed that contact lenses would no longer fit on my eyes.

This was not good news for me, not only emotionally, but financially. Inflation had caught up with the prescription lenses I required by that point with a new pair of eyeglasses costing me about $300.

Even at those prices, my insurance wouldn’t cover the more costly, thinner lenses and more attractive frames, so I found myself weighed down by “Coke bottle” glasses that gave me headaches!

Relief came when my vision difficulties progressed to the point where I needed cornea transplantation.

Because of the risk inherent in any (vision-related) surgery, eye surgeons will only operate on one eye at a time.

By the time I was ready for my other eye to receive a cornea transplant, the FDA approved (and my insurance covered) the less expensive (but more effective) intraocular lens.

By this time I had reached an age where I needed reading glasses. I tried them but didn’t like them, so to this day I use a magnifying glass, if need be, or simply increase the font size when I’m using my computer.

A side effect of the prescription eye drops used prior to, and following, some eye surgeries, including mine, was the premature development of cataracts.

The silver lining was that at a time when I would normally have developed the cataracts of aging eyes, I’d already had the surgeries a couple of decades before.

And while my vanity still keeps me from investing in glasses, I now not only appear to the uninitiated to have “perfect vision,” my eyes have formed a natural bifocal so that should I decide to cast my pride aside and buy a pair of eyeglasses, I won’t need bifocals.

While I might hope that keratoconus would lessen the odds of my developing macular degeneration and/or glaucoma, the fact is keratoconus has no impact on the odds of developing the diseases of aging.

At least keratoconus doesn’t increase those odds, though it still prevents me from being a candidate for LASIK surgery.

Given how far I’ve come, I think I can live with that.