Is it possible for an autistic person NOT to be disabled and never to have needed any social services or life skills support?

Is it only an illusion that having autism necessarily means a disability?

Perhaps you’ve been getting familiar with the popularity of the terms “high support needs” and “low support needs” in reference to Autism Spectrum Disorder.

This is an increasingly acceptable way to distinguish between mild autism and severe autism, or, to put it another way – a way that’s been losing acceptance – “low functioning” and “high functioning.”

There are nonverbal, very introverted autistic people who are fairly independent, have college degrees and have a professional job.

Meanwhile, there are very talkative, more people-interactive autistics who need substantial assistance in the activities of daily living.

Which one has the bigger disability?

Is disability determined by being unable to speak, even though that same person may be driving to work every day as a computer repair specialist?

Is the presence of a disability in ASD determined by frequency of meltdowns, intolerance of common environmental stimuli such as multiple simultaneous conversations in a room and fluorescent lighting?

Is an autistic person disabled simply because they tend to neglect their hygiene and get so caught up in their latest obsession that they forget to eat, feed the cat and pay bills on time?

My sister probably thinks I have a disability because, in her mind, childhood “intervention” of my autism would’ve made it more likely that I would’ve had a normal social life growing up and in adulthood.

But I’ve never felt disabled. I’m “zero support needs,” and in fact, have been a caregiver to both parents while they recovered from various major surgeries and experienced significant health problems.

I’ve interfaced with their medical teams, set up doctor appointments, organized my mother’s medications, arranged home services for my father, and the list goes on.

• One time on the job I ducked out of the department to avoid having to acknowledge a coworker’s new baby he was showing off.

I didn’t want to be placed in the awkward position of pretending I felt joy looking at someone’s new baby. I wouldn’t know what to say.

So rather than mask (fake an interest, complete with a phony voice and facial expression), I fled the department for 20 minutes, staying in the bathroom.

Some might say that this clearly indicates a disability, even though I’ve been 100 percent self-sufficient since 22.

However, there are people with various disabilities who are self-sufficient, such as those who use wheelchairs; those who are deaf; those with cerebral palsy.

So perhaps self-sufficiency isn’t the barometer we should use?

• I experience internal distress over things that don’t phase the majority of neurotypicals.

• Though I don’t have “autistic meltdowns,” I can get quite uptight when things don’t work right.

Superpower, not a Disability

©Lorra Garrick

“I don’t feel disabled by my autism,” says Jason San Souci, 43, diagnosed with autism at 42, who helps autistic people find employment in the drone industry.

“Instead, I feel like it has given me several advantages in life. The ability to hyperfocus, work extremely efficiently, see things differently, etc.

“There have been quantified studies that have measured the marked increase in efficiency, productivity and effectiveness of neurodiverse talent.

“I can typically accomplish in a few hours what it would take my peers all day to do.”

Clarissa Harwell was diagnosed with ASD at 43. “It doesn’t surprise me that many folks feel disabled by their being autistic,” says Clarissa, a LCSW and therapist.

“My answer may be different years from now, when I’m further in my journey of learning to unmask, but right now I do not feel disabled by being autistic.

“Part of this is probably because I can hide my autistic traits very easily when I feel I need to.

“I think living in a neurotypical world can feel disabling to many neurodivergent people because the world is set up to expect neurotypicality. The world does not readily accommodate divergences.”

Marleen Lam, 48, was diagnosed with autism at 38, and she doesn’t see it as a disability.

She explains, “Because perspective colors our perception: I prefer a growth mindset to a fixed or closed mindset.

“Life is short, so it’s better to focus on one’s strengths, keep on improving any perceived areas of weakness. Bit by bit it will improve.”

Are ALL autistic people disabled?

“Not all autistic people are disabled,” says Dr. Jessica Myszak, licensed psychologist, and director of The Help and Healing Center, whose practice is mostly autism assessment for adults.

“While autism spectrum disorder is considered a developmental disability, the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria includes this”:

- Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

“For many, this statement may be the difference between someone being diagnosed or not being diagnosed with autism,” continues Dr. Myszak.

“Autism is a brain difference, and for some, minor adaptations and accommodations are enough to support an autistic person in a neurotypical world.”

An example would be my wearing earplugs while on the job to muffle the annoying hissing that emanated from a neighboring room of computers (the big, old-fashioned kind that required cool ambient temperature). Nobody else in the large department had a problem with this noise.

One day I forgot my earplugs; it was awful. No meltdown, but I was uncomfortable the entire shift.

“A person can meet all of the other diagnostic criteria, but if they are not experiencing clinically significant impairment in some way, they would not meet the DSM-5 diagnosis of autism,” says Dr. Myszak.

Keep in mind that evaluators are human and come from all sorts of backgrounds and experiences, and thus, can be subjective in determining whether or not a person is autistic.

I’ve read posts in threads in which adults were denied the diagnosis because they said they had friends or gave the evaluator eye contact.

The psychologist who diagnosed me knew I gave decent eye contact, yet that wasn’t an issue to her in the least.

She also knew I didn’t have meltdowns or shutdowns nor ever had the infamous burnout (the latter which is clearly related to significant masking or faking being neurotypical).

Yet, during our final teleconference, her exact words were: “It’s pretty obvious you’re on the spectrum. To deny it I’d have to be blind, deaf and mute.”

Though her statement may sound insensitive, trust me when I say that given the context of our conversation and her tone of voice, she was actually validating my concern that I kind of didn’t feel “autistic enough.”

An autistic person who has the more dramatic, overtly visible experiences isn’t more autistic than is a “calmer” person with autism.

“The clinically significant impairment does not have to only be related to social-communication skills, and you would probably get different answers about this if you asked different psychologists,” says Dr. Myszak.

“I know there are psychologists out there who take a pretty black and white approach on this — if a person is working full time and has a family, they have a hard time saying that a person is experiencing impairment.

“Personally, my approach is that if a person is having to accommodate for something (e.g., they usually wear headphones out in public, but if they forget them, they have meltdowns; they work from home and get groceries delivered because in-person social exchanges are incredibly stressful; OR if they are having other significant mental health difficulties relating to being in a predominantly neurotypical world (anxiety, depression, eating disorder, etc.), that is evidence of this type of impairment.”

Would autistic people be disabled in an autistic-dominant world?

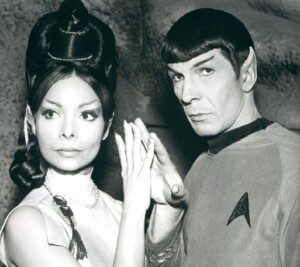

NBC Television/Wikimedia Commons

Imagine how well autistic people would fit in on Planet Vulcan – among a human species for which the following is non-existent: small-talk, sarcasm, indirect communication, flirtatious signals, the social requirement to smile and shake hands, social status, gossip, follow-the-crowd and herd mentalities and the normalization of making major decisions based on emotions rather than logic and facts.

Autistic people would flourish on Vulcan. Any NTs who continued acting neurotypical on Vulcan would quickly learn how out-of-place they were and may even begin “masking” to fit in – something that the autistics wouldn’t have to do.

The autistics would never suffer a burnout, while many of the NTs would eventually become overwhelmed and break down.

“If an autistic person has found their supports and are already making them, they may not look like they’re experiencing impairment,” says Dr. Myszak.

“But would they experience difficulty in another setting? I believe this is one of the core reasons why many adults have difficulty getting accurately assessed.

“Unless an evaluator really digs into what a person is experiencing on a regular basis, their areas of difficulty may be more difficult to identify.”

Undiagnosed and Under the Radar

It’s quite possible – very much so, actually – that there are many autistics among us who have no idea they’re autistic, and have been making it through life independently, albeit with social and sensory struggles.

Or, they may have been diagnosed but are doing quite well in the independence department, although perhaps bombing in the dating department.

Perhaps they’ve been fired from multiple jobs but then found new ones (I’ve been fired from four – due to not fitting in – but where I lack in the ability to fit in, I make up for in terms of perseverance and resourcefulness).

Maybe they found a job with minimal people interaction or figured out a way to work from home.

Or maybe they’re in a union, which means it would be very difficult to get fired.

Or perhaps they found jobs where it’s okay to be annoyingly quirky.

I’ve had jobs that were production-based; as long as I produced, I had the job.

I’ve been to several social functions for autistic people. These included loud noisy environments with multiple conversations going at once.

I’ve met an immigration lawyer, a former lawyer turned e-commerce entrepreneur, a school nurse, an architect, a military radar specialist, an IT specialist, an aspiring model, a film student, even a single foster parent.

They all (seemingly) gave good eye contact — not that stereotypical overtly staring downward when in conversation.

Perhaps these are the autists with “zero support needs.” But that’s not to say that they don’t make a lot of accommodations or experience internal distress when their routine is changed.

Jason San Souci is an autistic drone scientist. He is a graduate of the USAF Academy with a master’s of engineering from the University of Colorado. His mission is to elevate the drone industry through thought leadership and neurodiversity advocacy.

Jason San Souci is an autistic drone scientist. He is a graduate of the USAF Academy with a master’s of engineering from the University of Colorado. His mission is to elevate the drone industry through thought leadership and neurodiversity advocacy.

Clarissa Harwell, LCSW, has worked with a diverse range of clients for 15+ years including families experiencing homelessness, children who’ve experienced abuse and neglect, new parents, adults impacted by severe mental illness, and children and teens engaging in high-risk behaviors.

Clarissa Harwell, LCSW, has worked with a diverse range of clients for 15+ years including families experiencing homelessness, children who’ve experienced abuse and neglect, new parents, adults impacted by severe mental illness, and children and teens engaging in high-risk behaviors.

Marleen Lam, from Holland, is a former pediatric speech language therapist and sensory input therapist. Her passions are reading, teaching, child-development, cats, food, gardening and being outdoors. She writes for Keep Fit Kingdom.

Marleen Lam, from Holland, is a former pediatric speech language therapist and sensory input therapist. Her passions are reading, teaching, child-development, cats, food, gardening and being outdoors. She writes for Keep Fit Kingdom.

Dr. Jessica Myszak, a psychologist who specializes in autism assessment for both children and adults, is the founder of Autistic Support Network. She sees clients in-person in the Chicago area and over telehealth in 31 states. Learn more about her practice at helpandhealingcenter.com.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

.