Innovative technology makes endovascular repair possible for an abdominal aortic aneurysm when it’s close to the renal arteries.

Have you been told you can’t have endovascular repair of your abdominal aortic aneurysm because the defect is too close to the renal arteries, and that your only option is the invasive, open surgery?

There’s been a breakthrough in stent-graft “landing,” in that now, the stent-graft can be customized to accommodate the patient’s anatomy.

The projection is that this will eliminate a lot of open surgeries, allowing these patients to undergo endovascular repair of their abdominal aortic aneurysm.

One of the first U.S. hospitals to provide this new technology is Johns Hopkins Hospital.

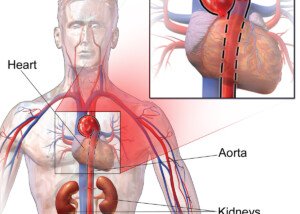

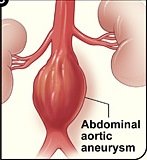

Historically, the open surgery has been performed in some patients because endovascular repair is not possible; the stent-graft would get in the way of the renal arteries because the abdominal aortic aneurysm is located too close to these vessels.

In stent-grafting (which is done by feeding a catheter through the groin to the abdominal aorta), room on either end of the graft is required to “land” it. This room isn’t there if the aneurysm is close to the renal arteries.

Though the open surgery is cheaper, it’s also much riskier (e.g., higher risk of kidney failure or heart attack) and can require up to eight weeks for recovery.

Prior to this new technology, the grafts used for endovascular repair were pulled off the shelves; not tailor-made for the patient.

“We need at least 5 millimeters to 10 millimeters of length between the renal arteries and the aneurysm in order to secure the stent-graft in place in most patients,” says surgeon James Black, in the report, from Johns Hopkins.

Dr. Black is one of only a few dozen surgeons in the U.S. who’ve been trained to make endovascular repairs of abdominal aortic aneurysms with this new graft technology, which was FDA-approved in April of 2012.

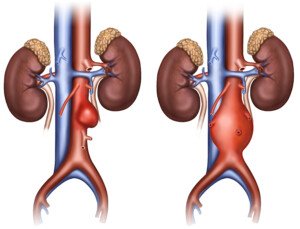

Traditional endovascular grafts are made of polyester fabric that’s encased in a stainless steel scaffold.

The newest development is similar, except that it has fenestrations: two little holes or openings fabricated into the graft, allowing accommodation of the renal arteries. These tiny holes help keep the device in place.

The graft must be “engineered correctly to match the patient’s individual anatomy,” explains Dr. Black.

Pre-surgical planning includes using a CT scan to create a 3-D image and model of a patient’s aorta. The construction of these grafts takes around five weeks.

Dr. Black says that every year, Johns Hopkins performs about 100 open surgeries for abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients who do not qualify (due to location of their aneurysm) for the minimally invasive endovascular repair.

But with the new fenestrated device, says Dr. Black, “We will be able to spare many of those patients a big operation and a long recovery.”