Ovarian cancer has a grim prognosis because it’s often discovered once it’s spread to other organs. But how does this silent and stealthy spread happen?

Most women aren’t diagnosed until the disease has already spread widely through the abdomen.

While researchers have long known that ovarian cancer progresses quickly, the biological reason behind this speed remained a mystery — until researchers from Nagoya University came up with an answer.

The study showed that ovarian cancer cells don’t act by themselves.

They recruit mesothelial cells, which normally line and protect the abdominal cavity. These cells move ahead, creating pathways that cancer cells follow.

Together, they form hybrid clusters that resist chemotherapy better than do cancer cells alone.

Hybrid Cell Clusters Form in Abdominal Fluid

Researchers analyzed abdominal fluid from ovarian cancer patients. What they found challenged previous assumptions. Cancer cells rarely float freely.

Instead, they attach to the mesothelial cells, forming compact, mixed spheres.

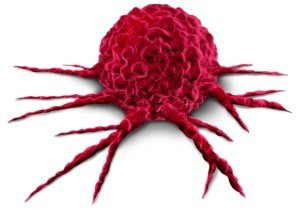

Cancer cells release a signaling molecule called TGF-β1. This transforms the mesothelial cells, which then develop sharp, spike-like protrusions that can cut through surrounding tissue. Below is a pictorial.

Shutterstock/Lightspring

How Ovarian Cancer Moves Inside the Abdomen

As tumors grow, some cancer cells break off and enter the fluid-filled abdominal cavity. The fluid moves constantly as you breathe and move, carrying cancer cells to different areas.

This method of spread is different from other cancers. Breast or lung cancer cells often enter blood vessels and travel through the bloodstream to distant organs.

Because blood follows defined paths, doctors can sometimes monitor these cancers through blood tests.

Ovarian cancer cells mostly skip the bloodstream. They float in abdominal fluid with no predictable route.

This floating phase happens before the malignant cells attach to new organs.

Until now, scientists didn’t fully understand what happens during this stage or how cancer cells coordinate such rapid spread.

Invadopodia: Spikes that Drive Tissue Invasion

During the floating stage, cancer cells recruit mesothelial cells that have naturally shed from the abdominal lining. Together, they form hybrid spheres.

The mesothelial cells develop invadopodia — spike-like structures that drill into nearby tissue. The image above of the single cancer “sphere” is pretty accurate.

These hybrid spheres invade organs faster and, as mentioned, are more proficient at resisting chemo drugs.

Using advanced microscopy, researchers observed this process directly in patient samples.

They confirmed their findings in mouse models and with single-cell gene analysis.

Lead author Dr. Kaname Uno, a former gynecologist and current Visiting Researcher at Nagoya University, explains that the cancer cells themselves remain largely unchanged.

“They manipulate mesothelial cells to do the tissue invasion work,” he says in the paper.

A Patient’s Story Inspired the Research

Dr. Uno spent eight years as a gynecologist before moving into research. One patient profoundly shaped his path.

She had normal screening results just three months before being diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer.

Keep in mind that, to date, no effective or reliable routine screening exists for this disease.

So for instance, a Pap smear is extremely reliable for detecting cervical cancer.

And the combination of annual 3D mammogram and ultrasound is highly effective at detecting breast tumors.

Screening for ovarian cancer for the typical woman comes down to a clinical exam during the yearly gynecological visit.

The patient succumbed to the disease; this motivated Dr. Uno to investigate why ovarian cancer spreads so quickly.

The findings suggest possible new approaches for therapy. Current chemotherapy targets cancer cells but doesn’t affect mesothelial cells that assist invasion.

Future treatments could aim to block TGF-β1 signaling or prevent the formation of these dangerous cell partnerships.

The research, published in Science Advances (2026), also points to new ways to track this stealthy killer. Monitoring hybrid cell clusters in abdominal fluid could help doctors predict disease progression and determine how patients respond to treatment.