A never-speaking or “nonverbal” autistic adult might one day say a word, then not say another for months.

How is this possible if the neural pathway for speech is severely impaired? Some nonspeaking autistic people can occasionally say a word or two, under certain circumstances.

I work once a week with a nonspeaking autistic woman of 25. There’s just no physical voice. When she gets into my car I always ask, knowing I’ll get only a smile, “How’s it going?”

But one day she said “good.” This was very surprising.

An Occasional Word in Nonspeaking Autism

So how might a “never speaking” autistic adult occasionally produce a word? One factor is motor planning. Speech requires precise coordination of breathing, vocal cords, tongue and lips.

According to a study by Dr. Helen Tager-Flusberg (Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2009), motor speech deficits and dyspraxia (neurological condition affecting motor skill planning and coordination) are common in nonspeaking autism.

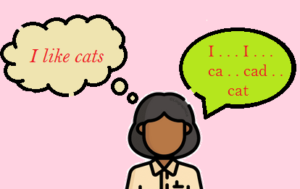

The neurological tract for speech begins in the brain (Broca’s area) with the intention to speak.

Normally, this intention fires along a complex neurological tract that culminates in physical output involving the vocal cords, mouth, lips and tongue.

In autistics who “can’t talk,” this tract is actually there, but it’s impaired enough to prevent speech, even a simple “yes,” “yeah” and “hi.” Think of their neurological tract as being offline 24/7.

But the woman I work with also one day said “hey” to get my attention when she was walking behind me.

This is someone whom if I have her take a comfortable seat and keep telling her to say her name or even just “hi,” nothing’s going to happen.

The impairment prevents deliberate speech — but not spontaneous speech in a spur of the moment state of excitement or eagerness, which involves a slightly less complex neurological chain of events when compared to more willful talking.

Emotional State and Motivation

Speech can appear in specific emotional or social contexts. Dr. Catherine Lord in a 2015 review (Autism Research) explains that nonspeaking autistic individuals are more likely to vocalize when highly motivated, excited or emotionally stimulated.

This explains the “good” and “hey.”

For example, hearing a favorite word or reacting to a preferred activity can sometimes trigger a spoken word, even if the person cannot speak on demand in other situations.

Remember, that neuro-motor planning tract is there, rather than non-existent.

Neurological Variability

Speech dyspraxia; impairment in Broca’s area. Pereoptic/creativecommons

Some nonspeaking autistics have intact language comprehension and cognitive processing — but show deficits in brain connectivity in areas responsible for speech production.

Dr. Ami Klin (Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2017), explains that this disconnect between understanding, and motor output, can produce “islands” of speech — moments when the brain just happens to successfully coordinate a word despite ongoing motor planning impairments.

Speech Is More Complicated than You Think

We take it for granted, but there’s a lot that goes on even though speech occurs within milliseconds from brain signal to muscle movement.

Let’s break this super fascinating sequence down in slow-mo.

First, the brain needs to form the intention to say something — like “want that” or a person’s name.

Then it must activate the language center (Broca), map sounds to muscle movements, and send signals to the mouth, tongue, jaw and breathing system in perfect timing.

For people with severe motor planning problems, that chain can glitch at multiple points.

They may know the word, understand language and want to speak, but the brain-to-muscle pathway is unreliable.

In my client’s case, her vocalization is limited to a breathy sound from prolonged exhaling with her mouth slightly open when she wants someone’s attention.

The words just don’t want to come, even though presumably, full intention is lit up in her brain.

However, in a moment of high motivation or emotional intensity (“How’s it going?”), the brain might manage to line up those signals well enough to push out one clear word.

Think of it like a rusty engine that occasionally catches and revs but can’t run consistently.

That one word doesn’t mean they can repeat it on demand — voluntary speech requires precise, repetitive motor coordination, not just a lucky burst.

So it’s possible for speech to appear briefly, almost as though the system aligned for a second, but that doesn’t mean the pathway is consistently available or controllable.

This phenomenon is also what occurs in some people who’ve suffered a stroke and can no longer execute speech or have limited speech.

![]()