Fat people are subject to ridicule and criticism for their weight, while anorexics somehow escape the vitriol and get compassion.

When a woman is notably underweight such as singer Ariana Grande and actress Tara Reid, they certainly will hear the occasional “Eat a cheeseburger!” from someone passing by in a car.

But when women are even thinner, such as influencers who appear to be in the throes of anorexia nervosa, and especially who are skeletal such as Instagram and YouTube presence Eugenia Cooney (see below), the snide remarks and ridicule are pretty much absent.

Eugenia Cooney/Instagram

Instead, many comments on reddit, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok are as follows:

- She needs intervention.

- This is so heartbreaking; I feel so sorry for her.

Of course, there’s always that very occasional comment of an insulting nature.

On the flipside, morbidly obese influencers such as Tess Holliday, Jaimie Weisberg, Amberlynn Reid and Anna O’Brien are the recipients of relentless ridicule, intense criticism and denigration – clearly displayed all over social media.

Before you insist that these particular women get lashed at because of their personalities or messages, there are plenty of other less-known, personality-neutral and significantly overweight women on social media who are viewed with disgust, disdain and zero compassion for their significant level of obesity.

- Morbid obesity reels in loads of cruel comments, anger and shaming.

- Anorexia nervosa pulls in loads of compassion and pleas to seek help.

What’s with the blatant dichotomy?

After all, both conditions – morbid obesity and anorexia nervosa – are caused by eating disorders. And both conditions often trace back to childhood trauma; many studies confirm this.

- A longitudinal study published in Pediatric Obesity (2013, Richardson et al) found that individuals reporting childhood sexual or physical abuse had significantly greater risk of developing severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40) in adulthood.

- A meta-analysis (Obesity Review, 2014, Hemmingsson et al) pooling 112,000 participants across 23 studies reported a 31% higher odds of adult obesity for those with childhood sexual abuse compared with never abused peers.

- For severely restrictive eating leading to significant underweight, a paper in International Journal of Eating Disorders (2014, Racine et al), explains that emotional abuse predicted severity of anorexia nervosa.

- A 2019 review in Cureus (Rai et al) reports that childhood maltreatment is disproportionately common among those with anorexia nervosa.

Of note: Many “thin” women report skinny shaming. However, they are not anorexic thin.

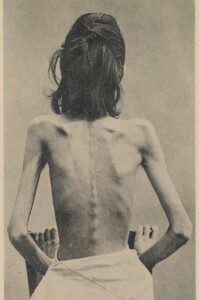

There’s a marked difference between “thin” Tara Reid and an anorexia nervosa patient, as shown below:

Anyways, when people shed sympathy and compassion towards emaciated women, they’re likely not thinking, “Poor thing, she must’ve suffered SA in childhood.”

When people direct disgust and cruel remarks towards 300 pound women, they’re likely not reflecting, “That’s what childhood neglect does to you.”

Instead, they base their reactions on the visuals.

What Our Eyes See and Brain Puts Together

We see obesity as gluttony and overconsumption, even as privilege in a world teeming with hundreds of millions of starving people in famine-ridden nations.

We see that very large person as able to crush things with their weight. We see greed.

We see anorexia nervosa as strongly resembling those very starving individuals in developing countries, and bodies that can be easily crushed rather than as the crusher. We see deprivation.

Thus, the human brain is apt to feel compassion and sadness for an emaciated woman, and contempt and blame for morbidly overweight women such as TikTok personalities Tess Holliday and Mary Fran — and even lesser-knowns who don’t promote obesity but simply make posts doing everyday ordinary things.

Mary Fran/TikTok

Social Media and Real Life

On social media platforms, morbidly obese women often get comments filled with outright hatred and accusations of draining societal resources with their gluttony.

Meanwhile, women who are extremely underweight tend to get overt pleas to seek help, along with plenty of sympathy.

But these dichotomous reactions to different eating disorders stemming from childhood dysfunction are often seen in “real life.”

A young woman of average height but about 300 pounds is walking along a pedestrian-heavy sidewalk wearing a tank top and shorts. Twenty minutes later, a young woman of same height but 80 pounds follows, wearing the same clothes.

We all know that for the first woman, thoughts will go towards disgust and contempt for “being a pig” without any consideration of root causes.

But thoughts for the second woman will go towards pity and wondering what horrible things had been done to her to “cause that” or – that maybe she has cancer.

This isn’t to say there aren’t exceptions, especially if the observer is a mental health counselor or eating disorders therapist.

One day at the gym I witnessed a very thin woman walk past a man.

The man looked at his normal-weight girlfriend and stuck a wiggling finger into his open mouth – clearly an imitation of self-induced vomiting.

But overall, we all know that fat people get scorned and “sickly thin” people get sympathized with.

Cultural Narratives

In many societies, thinness is idealized and seen as “discipline” or “self-control.” More extreme thinness may be interpreted as tragic — a person struggling with their health, eliciting sympathy.

Severe underweight triggers protective instincts in observers. Obesity, by contrast, is framed as laziness, gluttony or lack of self-control.

That protective instinct is absent because we associate very heavy things with forcefulness and power.

The Aesthetic Factor and Evolutionary Thinking

Though nobody could possibly see Eugenia Cooney’s body as visually appealing (except maybe other anorexics), her body is still on that same continuum of thinness that many see as a beauty standard.

So though 75 pounds on an adult woman conveys fright and shock, 110 pounds on a same-height woman can incite envy or come off as fashionably attractive.

A fat woman has limited clothing choices; a boney thin woman can “wear anything.”

From an evolutionary standpoint, a skinny body can move more efficiently, while a fat body is sluggish, can’t leap over boulders or run fast.

Now certainly, in developing countries where emaciation abounds, those individuals are too sick to be physically active.

However, move a little rightward on that continuum, and we get elite marathon runners, and 3,000 and 1,500 meter runners we all marvel at during the Oympics.

We get ballet dancers who enthrall audiences and ice dancers who wow spectators.

Now of course, if we move down the super morbidly obese continuum into a more “functionally obese” range, we’ll get the Olympic weightlifters, wrestlers, judo experts and shotputters.

But these sports aren’t as “feminine” as those of running, dancing and figure skating.

Far fewer moms imagine their young daughters as one day being a burly looking shotputter or powerlifter with a mix of manly muscle and excess fat than do moms imagining their little girl as one day being a slender cheerleader, lean swimmer or svelte dancer or model.

It’s Easier for Eugenia Cooney to Gain 40 Pounds than for Tess Holliday to Lose 200

Tess Holliday

If you had to choose an eating disorder IF you had to have one, in this thought experiment, would it be Eugenia’s or Tess’s?

Most women would choose anorexia nervosa, if for no other reason, it’d take far fewer pounds to get into a healthy weight range with anorexia than it would be if you weighed 400.

An average height woman with anorexia nervosa might need to put on only 30 pounds to reach a safe weight.

But a woman of 300 pounds average height would need to lose 150 pounds.

Which is easier? From a mechanical perspective, the weight gain is far easier and would also take much faster.

However, someone with anorexia nervosa is fearful of gaining even a single pound, and this prevents a much needed weight gain as much as compulsive overeating disorder or binge eating disorder prevents losing 100 pounds – even 50 pounds, for that matter.

Nevertheless, what seems like a simple straightforward solution with the emaciated woman has great appeal:

Just fill up on your favorite foods! Load up on the pancakes drenched in syrup and butter; eat a big steak every day; gorge on pizza and donuts!

Whereas with weight loss, we imagine ongoing hunger; forcing restraint; battling food noise and cravings; and not being able to indulge at events where food is bountiful.

Final Thoughts

It’s a harsh double standard rooted in cultural values, visual bias and misinformation about the causes of both conditions.

And there’s also a touch of evolutionary thinking: We’re genetically hardwired to view thinness as healthy (rightward on that continuum with the Olympic runners, not in Eugenia Cooney territory).

We’re genetically hardwired to perceive obesity as unhealthy and cumbersome, particularly Tess Holliday proportions.

Influencers who celebrate their morbid obesity will point out that excess fat protected primitive peoples during times of famine.

But there is no scientific evidence that excess fat in the form of morbid obesity contributed to survival of the human species during the Stone Age.

Ancient man had to be able to efficiently walk for miles – wearing just animal skins on his feet. Imagine a 250 pound body regularly making these long treks in the harsh elements. It didn’t happen.

Primitive peoples had to often run, leap, jump and climb for survival. Our distant ancestors were lean, not fat.

Prehistoric humans somehow made it through food shortages without becoming obese.

Both anorexia nervosa and morbid obesity reflect pain, control struggles and trauma, yet societal perceptions dictate who is condemned and who is consoled.

Again, to re-emphasize: This isn’t about skinny shaming someone who looks like Ariana Grande or Jennifer Aniston — which definitely exists. It’s about anorexia nervosa-shaming — which essentially is non-existent.

One final note: Not all morbidly obese individuals had a traumatic childhood; there are many exceptions.

A person may have simply grown up in a household where family events and happy times revolved around food abundancy, and fatness was the norm for them and extended family.

One of my nieces reached about 250 only in young adulthood; she had a fabulous childhood.

The many fat kids of today are products of fat parents who allow food freedom; doesn’t mean the kids are physically or mentally abused.

In the U.S., it’s super easy to pack on the pounds in adulthood.

With that all said, when people become super morbidly obese, coming in at 300+ pounds for women and 350+ for men — there’s a much stronger correlation with a painful childhood — even if they were normal weight in childhood.

![]()