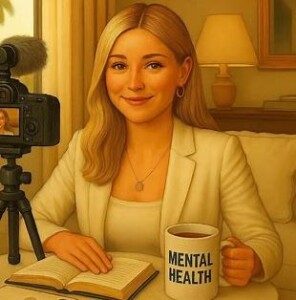

Scroll through Instagram or TikTok and you’ll find many body image and mental health influencers sharing stories of “healing journeys.”

Some have been in therapy for years — a decade, even — talking openly about self-esteem, anxiety or body image struggles.

What stands out is how so many of these voices come from women who, by most measures, started life on easy mode: private schools, vacations in Italy and Cancun, giant family homes in gated communities, and parents who are still happily married.

So why are so many young women who’ve had “everything” growing up also among those who seem emotionally adrift?

Why do so many highly privileged body image and mental health influencers describe themselves as “in recovery,” “healing” or “doing the work” — seemingly forever?

Growing up Protected from Pain

One explanation may be that growing up with wealth and privilege can paradoxically limit mental resilience.

When you’re cushioned from failure and discomfort, you may never fully develop the coping mechanisms that come from dealing with issues of challenge – or even what seems like run-of-the-mill realities of life.

Research in Frontiers in Psychology (Luthar, Barkin & Crossman, 2013) found that adolescents in high-income families actually report greater rates of anxiety and depression than do their middle-class peers.

This is partly because of parental pressure to excel and partly from emotional disconnection within achievement oriented households.

The pressure to excel may be in academics, music and/or sports.

That emotional insulation often extends into adulthood.

A person raised in an environment where problems were solved with money or influence can find ordinary disappointments — rejection, career uncertainty, not being as thin as their friends, favorite TV stars or recording artists, missing some shots during their college sports match — disproportionately painful.

Therapy, then, becomes less about processing trauma (e.g., childhood sexual assault, physical abuse from a parent, multiple deaths in family when growing up, parents’ divorce, chronic debilitating illness, homelessness) and more about managing the discomfort of not always getting what you want.

The “Therapy as Lifestyle” Generation

There’s also a cultural layer here. Over the past decade, therapy has become not only normalized but sometimes even fashionable.

Influencers post “mental health check-ins” alongside sponsored self-care content.

Therapy becomes part of the online persona — proof of self-awareness, sensitivity and depth.

A 2023 study in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology (Baum & Lewis, 2023) notes that Gen Z and millennial women are more likely to view therapy as a form of identity work rather than as crisis intervention.

In that sense, long-term therapy isn’t necessarily a symptom of distress — it’s part of the brand.

But for wealthy influencers, the aesthetic of therapy (“I’m healing” or, “I had a good cry in therapy today”) can merge with self-marketing, blurring the line between genuine introspection and performative vulnerability.

Privilege and the Body Image Paradox

You’d think that growing up with access to the best education, dental care, skincare, wardrobe and accessories, recreational activities, and skiing and beach vacations would protect against body dissatisfaction — but it often doesn’t.

In fact, exposure to perceived elite beauty standards and constant comparison can make things worse.

A large-scale review in Body Image (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2022) found that young women from higher socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to engage in appearance-based social comparison and to experience body dissatisfaction, even when their objective body metrics fit conventional beauty standards.

For influencers, that pressure is magnified: Their livelihood often depends on how they look.

The wealth that buys them access to beauty “optimization” also traps them in the very perfectionism that fuels their mental health content.

When these women then build platforms around “authenticity,” “self-love,” “no filters” and “being real,” they face a double bind:

Their success still hinges on appearing attractive and aspirational, even as they preach acceptance.

That inner contradiction can create chronic tension — and keep them in mental health therapy for years, trying to reconcile image with identity.

Can Achieve but Can’t Cope

Another factor is that many affluent families value achievement, control and external success.

If you grow up where emotional pain is managed quietly and appearances matter most, you might reach adulthood knowing how to achieve but not how to cope.

A 2021 paper in the American Journal of Psychiatry (Ehrenreich-May et al.) explains that adolescents from overinvolved or “helicopter” parenting environments showed weaker stress tolerance and higher emotional reactivity.

The helicoptering could occur in any number of contexts such as music recitals/performances and athletic matches.

This all carries into adulthood as what some psychologists call “fragility of privilege” — the inability to calibrate emotion because life’s friction points were always smoothed over.

For a “full-time” influencer who’s never faced real material scarcity or instability, even small emotional discomforts can feel enormous – such as feeling overwhelmed by too many weddings to attend, how to organize lazy weekday mornings and feeling like a traitor when holding in their tummy for a group photo.

Therapy can become a perpetual attempt to locate meaning and identity in a life that already has all the external markers of success.

Accountability, not Blame

Of course, this doesn’t mean wealthy influencers are faking their struggles for engagement and more followers.

Their kind of mental pain is still pain, and privilege doesn’t immunize anyone from insecurity, anxiety or self-loathing.

But it does shape how people interpret and respond to those feelings.

When your hardships are mostly internal, therapy often becomes about untangling existential dissatisfaction — “Why don’t I feel fulfilled?” — rather than recovery from traditional forms of trauma.

Sociologists have observed that affluent individuals sometimes experience what’s called “affluence induced alienation.”

In Sociological Inquiry (Kasser, 2016), material wealth correlated with lower life satisfaction once basic needs were met, suggesting that excessive comfort can erode purpose and self-efficacy.

The Privilege of Endless Focusing on Self

It’s also worth acknowledging the privilege of access to good therapists, to time, to money, to mental health language itself.

Many people can’t afford a single session, let alone a decade of weekly therapy.

For some body image and mental health influencers, therapy becomes another form of consumption: one more tool for personal optimization, like Pilates or green juice.

That doesn’t invalidate the work they’re doing — but it does raise questions about what “healing” means when it’s sustained indefinitely by privilege.

At what point does therapy shift from exploration to indulgence?

This is a fair question, especially when the therapy drags on for years, yet the influencer continues to experience the same mental health issues she’s had since starting her accounts.

How do these disenchanted “fake confidence” women get such huge followings?

It might seem paradoxical: Influencers who openly discuss therapy, anxiety and body image struggles can have massive followings.

Wealth and privilege help explain part of this phenomenon.

First, relatability draws followers. Audiences see influencers as “real” because they share vulnerability.

A 2022 study in Computers in Human Behavior (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2022) found that audiences are more likely to follow and engage with influencers who reveal personal struggles, particularly around body image.

For influencers born with that proverbial silver spoon in their mouth, their vulnerability is packaged alongside aspirational lifestyles — bedroom-size walk-in closets, designer wardrobes, killer handbags, luxury trips and high-end wellness routines — creating a blend of relatability and envy that’s irresistible to audiences.

Second, wealth provides the resources to amplify influence.

High-end cameras, professional lighting, content teams and access to curated experiences make posts visually polished and algorithmically favored.

These influencers can afford to post consistently, experiment with trending formats and collaborate with other high-profile creators.

Research in the Journal of Media Economics (Marwick, 2021) explains that social media success is often correlated with access to financial and social capital, not just content quality and conventional good looks.

Third, personal struggles themselves become compelling content.

Audiences are drawn to narratives of emotional complexity, and algorithms reward engagement — likes, comments and shares.

For influencers raised in glittery comfort, their mental health stories are dramatic yet relatable.

They illustrate the tension between material abundance and internal dissatisfaction, a story that resonates widely.

![]()