Most cancer treatments are built around one core idea: destroy the cancer cells.

Chemotherapy, radiation and even many newer immunotherapies are designed to damage tumors until they can no longer survive.

But a growing group of researchers is asking a very different question. What if curing cancer isn’t always about destruction, but about helping cancerous tissue heal instead?

This unconventional idea is being explored by Professor Indraneel Mittra at the Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer in Mumbai, India.

His work suggests that cancer may sometimes be pushed into a calmer, less aggressive state rather than attacked outright.

Cancer as a Wound That Never Heals

The concept isn’t entirely new. Decades ago, researchers noticed that cancer behaves a lot like a chronic wound. In 1986, Dr. Harold Dvorak famously described cancer as “a wound that does not heal.”

Both cancer and chronic wounds share similar biological signals, including inflammation, abnormal cell growth and immune system changes.

Professor Mittra argues that instead of focusing only on killing tumors, medicine should also explore ways to help them resolve and stabilize, much like a wound that finally closes.

This idea recently moved from theory to real-world testing in patients with glioblastoma.

Why Glioblastoma Is So Hard to Treat

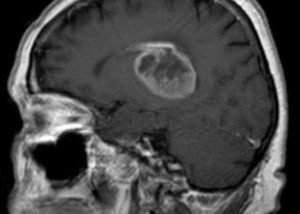

Glioblastoma multiforme is one of the most aggressive and deadly brain cancers. Even with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation, patients typically survive only about 15 months after diagnosis.

Because current treatments offer limited benefit, glioblastoma is often used to explore new and experimental approaches.

In a study published in BJC Reports, Professor Mittra and his team tested a surprisingly simple strategy involving two nutraceuticals: resveratrol (a compound found in red grapes) and copper.

The study included 10 patients with glioblastoma who were scheduled for brain surgery. For about 11 days before surgery, they took a tablet containing small amounts of resveratrol and copper four times a day.

Another group of 10 patients with similarly aggressive tumors did not receive the tablets and served as a comparison group.

During surgery, tumor samples from both groups were collected and analyzed using advanced laboratory techniques to examine how the cancer cells behaved at a molecular level.

What Changed Inside the Tumors

Tumors from patients who took the nutraceuticals showed much lower levels of Ki-67, a marker that indicates how fast cancer cells are dividing. This suggests slower tumor growth.

Markers tied to major cancer-driving processes were present in far fewer cells.

Immune checkpoints, which normally help cancer hide from the immune system, were also significantly reduced.

Markers linked to cancer stem cells, often associated with treatment resistance and spread, dropped sharply as well.

Notably, none of the patients experienced side effects from the tablets.

How Cell-Free Chromatin May Drive Cancer Aggression

Professor Mittra believes the key lies in cell-free chromatin particles, or cfChPs. These are fragments of DNA released when cancer cells die.

Instead of being harmless debris, they can inflame nearby cancer cells and make tumors more aggressive.

Earlier research showed that when resveratrol and copper are combined, they generate oxygen radicals that neutralize these DNA fragments.

In this study, cfChPs were abundant in untreated tumors but nearly absent in tumors from patients who took the nutraceuticals. This suggests dying cancer cells were cleared more cleanly, without triggering further damage.

One of the most intriguing findings was the reduction in immune checkpoints. Modern immune checkpoint drugs can be life-changing, but they are extremely expensive and often come with serious side effects.

In contrast, this nutraceutical combination is inexpensive, widely available and nontoxic, yet appears to affect similar biological pathways.

Rethinking the Future of Cancer Treatment

Professor Mittra believes these findings could point toward a major shift in how cancer is treated. Helping tumors heal instead of attacking them may sound radical, but the early results are hard to ignore.

While the study was small, the changes seen in tumor biology were dramatic.

Larger trials will be needed, but this research opens the door to a new way of thinking about cancer treatment, one that focuses on calming the disease rather than waging war against it.