Do ALL autistic women have burnouts? If not, are they “less autistic” than those who have? Autistic burnout is the result of long-term masking that eventually can no longer be sustained.

Masking refers to altering behavior to conceal autistic traits and/or tacking on behavior to mimic that of neurotypical (NT) people.

I was diagnosed with ASD in middle age.

When autistic people mask, it’s always a conscious or mechanical behavior, rather than an intuitive or instinctive one.

The behavior that they’re trying to mimic comes naturally, subconsciously and instinctively to neurotypicals.

This means that masking requires conscious energy, while for NTs, the same presentation takes little to no energy.

Though an autistic woman can sometimes end up doing some masking subconsciously from having done it for so long, it’s still, overall, a conscious act that requires cognitive workload.

Eventually, the workload exceeds capacity, leading to autistic burnout, which can damage mental health.

It Begins with Masking

Somewhere in childhood, an autistic girl will begin realizing she’s “different.”

To remedy this, she will consider the idea of copying the behavior of classmates.

- She watches their facial expressions and body language.

- She listens carefully to their tone of voice and how they verbally respond to common questions and statements.

- She may spend a lot of time practicing what she’s observed, even using a mirror.

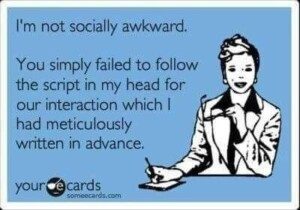

- She’ll memorize words to respond to various questions and comments so that she’ll always have a script ready.

- Some autists can become so prolific at masking that they easily “pass” as neurotypical.

Neurotypicals may mask, too, in certain situations. But they don’t have to do it as in-depth to fit in or feel accepted, and it also comes way easier to them.

Are you an NT who can’t understand autistic burnout?

Perhaps the toughest masking job for an NT is a major job interview.

For around 45 minutes the NT is in full interview mode. They’ve rehearsed answers, even facial expressions, for anticipated questions.

They’ve practiced how they’re going to sit. They may have even practiced out loud the “I want to work for your company because…”

Once in the interview they’ll still be very consciously aware of every little detail, such as what their hands are doing as they speak; how their legs are positioned; are they sitting too relaxed? Should they lean a bit towards the interviewer?

They’ll make a point to smile when the interviewer does, or even chuckle when the interviewer makes a poor attempt at humor.

They make sure not to tap their fingers or fiddle with a necklace to avoid looking nervous. They are continuously mindful of the volume of their voice.

Once the interview is over, the NT job seeker can relax and may feel drained.

But 20 minutes later they’ll be good to go. It’s not as though LIFE is a never-ending job interview.

But what if it were?

Imagine that you must maintain interview mode eight hours a day, five days a week, week after week, month after month, in order to keep your new job.

How long could you sustain this conscious workload?

Imagine you had to apply it outside the workplace, such as when around your significant other’s family.

Imagine believing that if you slip up only a few times, you’ll get fired, or your friends (who don’t know the real you) will no longer want to be your friends.

So you keep up the full interview mode. HOW LONG can you sustain this facade?

If you lived in a world in which dropping interview mode would cost you, the stress and anxiety of maintaining it would eventually roast you.

In autism, the “interview mode” is an attempt to pass as neurotypical.

The consequences of accidentally unmasking or “slipping up” may not be as bad as the Autist believes, but that’s beside the point.

Ongoing masking cannot be sustained and will lead to an autistic burnout.

A great question is: Do all autistic people eventually experience this autistic burnout?

Clarissa Harwell, LCSW, is a therapist diagnosed with autism at 43. She has never had an autistic burnout — because she has a plan in place to prevent it.

Clarissa explains, “In terms of preventing burnout, when I am getting stressed and overwhelmed in the longterm, I reduce scheduled activities and slow down a lot.

“I do fewer things. I make my days as uncomplicated as possible.

“This might mean simpler meals, going out of the house less, fewer chores, less noise and overall fewer demands of me and my time/attention.”

As for myself? I’ve never had an autistic burnout, but my reason is because I never masked enough.

The first phase of the process is realizing you’re different. The second phase is what I’d call “self-editing.” I came up with this term before I began suspecting I was autistic.

Self-editing was when I’d be too aware of how I was presenting myself when in social environments.

Was I too loud? Too quiet? Too serious? Too opinionated? Gruff? Were may facial expressions weird? Did I not smile enough?

Did people think my personality was off-putting? What about my mannerisms? My voice? I was sick of going through this damn checklist all the time.

This checklist either leads to the pursuit of masking (the third phase), or, an “I no longer give a flying fuck” attitude. I opted for the latter. It was much easier!

My take was this: If people, whom I don’t even care for, think I’m strange, too difficult, too abrupt, “anti-social” or what-have you, then that’s THEIR problem.

- I can’t make it MY problem.

- I am me.

- I can’t pretend to be someone else and go against my grain.

And trying to act (pass as NT) like people I didn’t even like made NO sense!

I resigned to the fact that whatever group of people I’d be among in life, they’d soon enough realize that something about me was “off” or different. I had to accept that I’d never have naturally-occurring social skills.

“We can’t be good at everything,” I’d reflect.

“I excel in some areas — but bomb with people. I can’t fight it.”

Thus, I never got to the third phase: masking beyond a bare minimum. Hence, I’ve never had an autistic burnout.

In an “identity therapy” session following my ASD diagnosis, the psychologist explained that autism is a spectrum, that every Autist is different from other Autists.

She also pointed out that autistic burnouts get a lot of attention, while their absence doesn’t attract discussion. This creates the illusion that burnouts automatically come with autism.

I never had a strong craving for friends; why mask? To gain what?

I tried some masking in adulthood to be wanted on a competitive volleyball league.

It was frustrating, but not extensive enough to cause a burnout. I eventually gave up volleyball.

“Many autistic individuals experience burnout at various times in their life,” says Dr. Jessica Myszak, licensed psychologist, and director of The Help and Healing Center, whose practice is mostly autism assessment for adults. (She was not involved with my diagnosis.)

“Burnout is directly related to the amount a person masks, so many people who mask extensively have significant episodes of burnout,” continues Dr. Myszak.

“Masking can be socially reinforced, taught and encouraged by parents or various therapies, or self-imposed by the person based on the way they feel they are expected to act.

“However, not all autistic individuals mask. This may be due to a person’s personal characteristics or their environment. Those who do not mask may well never experience burnout.”

I’m not saying I’ve never masked. Of course I have! But I never worked at it hard enough to pass as “normal.”

The two longest jobs I’ve ever had were jobs where one could get away with being weird; they were productivity-based jobs.

You could be as weird as a pink cucumber, but as long as you pumped out the work, you had a job.

However, I’ve had a few part-time jobs where social awkwardness was not as tolerated; I got fired from those.

I’ve also had jobs working with cognitively challenged adults; I easily got away with being “different.”

Since my ASD diagnosis I’ve let the little mask slip off. I now stim a bit more in public. I let my face rest more often in its natural state. I’m more straightforward and direct than ever.

The only mask I’ll happily wear is the one to help protect against COVID-19.

Clarissa Harwell, LCSW, has worked with a diverse range of clients for 15+ years including families experiencing homelessness, children who’ve experienced abuse and neglect, new parents, adults impacted by severe mental illness, and children and teens engaging in high-risk behaviors.

Clarissa Harwell, LCSW, has worked with a diverse range of clients for 15+ years including families experiencing homelessness, children who’ve experienced abuse and neglect, new parents, adults impacted by severe mental illness, and children and teens engaging in high-risk behaviors.

Dr. Jessica Myszak, a psychologist who specializes in autism assessment for both children and adults, is the founder of Autistic Support Network. She sees clients in-person in the Chicago area and over telehealth in 31 states. Learn more about her practice at helpandhealingcenter.com.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

.