Autism awareness is not autism acceptance. Here’s what you may NOT know about autism.

Autism is a disability that may, depending on the person, come with social and sensory processing differences, a need for augmentative or alternative communication (AAC), as well as difficulty with transitions, executive functioning and more.

However, before I move on, I’ll add that not every autistic trait is disabling.

(And not all autistic individuals consider their neurodivergence to be a disability.)

Intense interests, for example, a word coined to replace special interests, are not only common but are often portrayed in popular media about autistic people.

Intense interests can be described as one or more subjects that an autistic person will not only develop, per the word, an intense interest in, but that may also learn as much as they can about so that, with enthusiasm, they can share the knowledge that they’ve learned with those they trust.

On that note, there’s more to autism, and the autistic experience, then is usually discussed.

First, I’ll define autism acceptance and provide an example of how the pandemic has affected autistic people.

Then, I’ll describe two autistic traits that don’t get nearly as much attention as they should, and share much needed information about them.

I’ll wrap up with my final thoughts on autism acceptance month and the use of identity-first language (e.g., autistic person/people) over person-first language and, per the title, I’ll end with a question.

First, the Autistic Self Advocacy Network has described autism acceptance as an action, as something that we intentionally do, every day, for the autistic people in our lives, whether they’re us ourselves or someone we know.

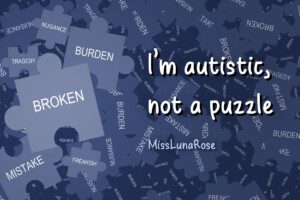

MissLunaRose12, CC BY-SA 4.0creativecommons.org

It’s more important now than ever during the pandemic, where many autistic people have lost access to their communities, their care and other parts of their daily routine that have been much more digital for public safety.

While this isn’t the case for everyone, technology can be inaccessible for some autistic people, so some may continue to lose access to needed individual care and community support because of the pandemic until this is addressed.

Next, I’ll mention some of the autistic traits that aren’t always talked about.

Sensory hyposensitivities, not hypersensitivities, are experiences where autistic people can be easily underwhelmed, and not overwhelmed by certain sensory input.

An autistic person who is hypersensitive, for example, might avoid loud noises and may wear noise cancelling headphones.

However, an autistic person who is hyposensitive might only listen to loud music and may want to be as close to the noise as possible.

This isn’t specific to sound only, and if you remember that there are more than five senses, then this becomes more complicated.

Seventy-four percent of autistic adults in a study (Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Fiene et al) were found to have a higher difficulty with something called interoception, which is a person’s sense and understanding of their body’s signals or cues.

This can be everything from feeling hungry, thirsty, tired or nauseous, to feeling hurt, hot, cold, sick, or for autistic women who menstruate, knowing if they’re on their period.

This can make it difficult for some to take care of themselves, eat/drink/sleep regularly, or get needed care because they may not always know that their body needs something.

Some, for example, may need to set alarms, reminders or use certain apps as an accommodation if they struggle to understand their body’s signals or cues.

It may explain why, for example, an autistic person who’s done well at caring for others may forget to drink water or eat for more than a day because they cannot tell that they’re hungry or thirsty.

Meanwhile, it can shed light on why an autistic adult who menstruates may continue to struggle with tracking their period, regardless of their age or experiences, because they cannot anticipate it until it happens.

Relatedly, because many autistic people like me are also transgender, autistic people who menstruate may struggle to know when their periods are coming and then suffer from what, to some, seems like intense, ‘last minute,’ gender dysphoria that feels chaotic and unavoidable.

Otherwise, autistic people, time after time, have discussed why saying autistic, autistic person, and/or autistic people makes them feel more comfortable and feels more accurate for them.

The common argument I’ve seen about what person-first language sounds like to many autistic people is that of comparing how it sounds when you aren’t putting the person before the autism.

Let me explain. What if someone said she was a woman, and someone she didn’t know (on social media, for example), immediately responded by saying that’s an “inaccurate,” “offensive,” or even an “insulting” way to describe that person — and that, out of respect, you can only call her a “person with womanhood.”

When asked to explain why, that person says, “You have to put the person first.” That would never be an acceptable way to talk to a woman.

But, as an autistic woman myself, I can tell you that autistic people are spoken to like this every day, and it can have horrible consequences.

I personally know too many autistic people, and other people with different disabilities, who told me that I’m the only person anywhere who can ever know that they are autistic, or have a different disability, because they’re afraid of backlash.

They’re afraid that they won’t be heard and valued, won’t be listened to and respected, that they won’t be safe or accepted by the people they know if they ever found out that they are autistic, that they are disabled.

I think about those people every day as we get closer to April.

With Autism Acceptance Month and beyond, I hope you’ll remember that an autistic person or someone with other challenges – who wants to feel comfortable with you and honest about whom they are – is not an insult.

In other words, our needs are not special because they make the world around us uncomfortable.

Right now, as I finish typing this sentence, and you finish reading it, someone is autistic and they do not feel safe.

They do not feel safe because of the potential reactions of the people around them to a simple, unavoidable fact that hurts no one.

Please do what you can to learn more about autism, autistic people, autism acceptance, and the best ways to support the autistic people you know and what cross-disability advocacy can do.

While I do the same, I’ll remember people who have to keep themselves secret this April.

I’ll remember hushed moments where someone trusted me with a sentence that the world has never heard them say: “I am Autistic.”

I will remember that they are unsafe, and I will ask myself one of many questions:

What is autism acceptance in a world that autistic people cannot come home to?

Sylvia is an Autistic transgender social worker for autistic and transgender communities. Her work on peer mentor training and health/wellness for Autistic communities has reached campus-based, cross-county, national, and international audiences. She welcomes you to connect via email: [email protected]