Fearing you won’t last on that upcoming grueling hike?

This smart routine will prepare your body for handling the hills with grace.

Maybe you spend a lot of time on a treadmill at 15 percent incline in an effort to hone hiking fitness.

But if you’ve been holding onto the machine, then count yourself out from having acquired strong and efficient hiking muscles.

Holding on totally eliminates the training effect of the incline.

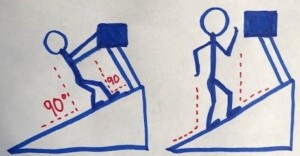

If you’ve been holding onto an inclined treadmill, ask yourself which illustration looks more like the angle of one’s body when walking up a hill outside? This is an no-brainer. Holding onto a treadmill will sabotage your attempts to acquire hiking fitness.

On the other hand, if you’ve been swinging your arms the way you would on an outdoor hike, consider yourself a great candidate for a rigorous, invigorating trek on the trails.

Better yet, if you’ve already been hiking for some time and would like to make the leap to the next level, there are specific techniques that will get you there rather quickly.

Footwear

If you don’t have footwear specifically for hiking, you need it for more demanding hikes.

But if you go hiking right away in new shoes, you’ll probably end up with blisters and ruptured skin.

Get used to the shoes around the house first. What may feel very comfy in the store, may prove to be very irritating once you’re in them for a while.

When it’s time to try them out on actual rough terrain, limit your time to 30-45 minutes, depending on how your feet feel. Each time you hike, stay out a little longer.

Length of Training Sessions

I have found that to prepare for a brutal 8-10-mile group hike, you need train for only 90 minutes to two hours.

You won’t cover near this distance, but if this relatively short excursion is intense enough, it will be sufficient to prepare your body for literally an all-day hike with a group.

In group situations, there are more rests than you would take alone.

Secondly, the pace is determined by the slowest hiker.

Though faster people may be way ahead of the straggler, they also get to rest while the straggler(s) catch up.

If your intention is to go solo on much longer hikes—again, training for just 90 minutes to two hours will do the trick—if, and only if—you incorporate a wonderful concept called high intensity interval training (HIIT).

Observe other hikers next time you’re on a trail. Their pace is fixed. They are on cruise control.

They may slow down upon meeting up with very steep portions of a trail. But for all practical purposes, their speed is “steady state.”

This kind of training has limitations, and it’s fine if your goal is to maintain your current fitness level.

High Intensity Interval Training

If you want to transform your body into a mean hiking machine, you must do something above and beyond mere steady-state exercise.

The first step is to find an area that offers varying degrees of steepness and terrain surface.

The best training venue involves level to very steep grades, and surfaces of rocks, pebbles and earth, and grass.

Since you are already base-conditioned, start out with a five-minute warm-up; a brisk walk. Usually, the first five minutes of a trail are fairly level.

After five minutes, pick up the pace some more. If it will be a while before you hit the first grade, then maintain your quick pace.

Now, every time you’re about to encounter a moderate to steep section of the trail, charge up as fast as you can.

Shutterstock/ManuelfromMadrid

If the steep part is really, really long, then just keep charging until you become quite breathless.

Then, slow down to a very leisurely climb. Do not stop! Keep moving! You will be heavily panting, but keep ascending very, very slowly.

After 2-3 minutes…it’s time to go full steam again. Keep doing this until the steepness tapers off.

Once you’re back on minimally steep or level ground, resume a brisk pace. If you need to go slowly on a level course to regain your energy, then do that.

But once that energy is regained and you’re no longer breathing hard, bump up the pace.

If the trail has only very short segments of considerable steepness, then commit yourself to stampeding up them until you reach the top.

Each stampede should be all-out effort, and depending on the shortness of the steep portions, these “work” intervals may last only 10-30 seconds.

But that’s perfectly okay. A multitude of 10-30-second high-intensity intervals will create an astonishing training effect in your body.

In fact, so dramatic is this training effect, that if you hike this way only once a week, you will notice improvement in performance each week.

You also needn’t spend the entire 90 minutes to two hours slamming yourself with HIIT.

You can do it for the first 45-60 minutes (though as time progresses, you’ll find that your investment in the “work” intervals will be diminishing).

Then, spend the remaining time in a steady-state zone, but make sure you have to work hard for it.

If the remainder of your hike is spent walking leisurely, as though you are sight-seeing, trying to identify flowers and admiring the cloud formations, you will be depriving your body of the training necessary to confidently take on a grueling 8-mile or longer hike.

And the thing about group hikes is that you won’t know what the collective fitness level is until after you begin the hike. You might end up being the straggler!

To guard against this possibility, train fiercely. Not just to keep up with the group, but to also minimize injuries.

Many people will go on a lengthy hike, thinking they’re prepared because they hike three times a week for two or even three hours.

But then they are shocked to discover that in a group situation, they are straining to keep up and in pain. Why?

Because the collective conditioning level is way beyond them. Everyone else wants to go faster. Or, the hiker is totally unprepared for the particular terrain.

Did you know that hiking hard only on pebbly-earthen surfaces will not prepare you for tundra?

Even climbing on stair-case-like, man-made paths of big rock chunks won’t prepare you for tundra—which is essentially grass; but very long, thick grass. Often, little rocks are embedded in tundra.

When climbing steep tundra, the calves and Achilles tendon are recruited far more than when climbing surfaces studded with rocks and large stones.

Also, ascending a steep forest bed will really hit the calves and Achilles tendons. So always make sure you get in some tundra training.

Cross-training at the Gym

In addition to the treadmill, you can do step aerobics—but use as many risers as you can manage.

Most people use one or two. A serious hiker-in-training should use four of the risers on each side of the stepping platform.

And you needn’t be fancy with dance moves, twirling or pivoting.

Simple stepping up and down, but briskly, is all that’s necessary. But include straddle-stepping.

Don’t wait for a class. You can do this during non-class times. Grab a platform and risers and just go at it for 20 minutes non-stop—four risers.

Don’t go to five until you sense that your calves and Achilles tendon won’t be overstrained.

And don’t wonder what to do with your arms while you’re stepping in solitude.

When you hike, you don’t do arm choreography.

Thus, it’s totally unnecessary when you step-train for hiking. Just let the arms move as though you’re on a real hike.

Additionally, include squats, leg presses, leg extensions and leg curls in your regimen. These will lower injury risk. Happy hiking!

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health. She has gone on many hikes with the Colorado Mountain Club.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health. She has gone on many hikes with the Colorado Mountain Club.

.