Why the Femur to Torso Ratio in Squatting Is NOT Nonsense

There is solid truth to the claim that a bad femur to torso ratio will make back squats very difficult; learn why this is not a lame excuse!

Are you one of those “bro science” guys who slams some dude in a fitness forum because he blames his back squat problems on long femurs and a short torso?

That’s odd, because it’s Physics 101.

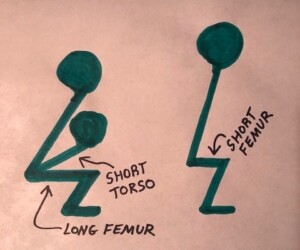

It’s also a matter of halfway-decent vision, when you view the two images below.

The one above shows lousy squat proportions;

in the one below are blessed squat proportions.

Do you really think the guy in the first photo shouldn’t have a much harder time with the back squat, with those relatively long femurs having to go through a greater arc of motion — relative to the shins — to get parallel to the floor?

Imagine him squatting. Then imagine his better-proportioned twin doing the same. Come on now, who’s going to have a real bear of a time here?

And no, the difference isn’t a bigger pair of pants. Look again at the torsos, then the femurs, then the shins.

Short femur athletes know only one thing: What the back squat feels like with short femurs and a long torso (or at least, a torso that’s not shorter than his femurs).

Likewise, the person with the “biomechanical disadvantage” knows only one thing:

That he will fall backwards as he lowers into a half squat, unless he pitches his torso WAY forward — maybe even turning his squat into a good morning.

Though there are those with long femurs and a short torso who actually perform the back squat, you should realize that piling on heavy weights is not a smart idea because their lower back is forced to absorb a lot of tension.

Marvel of nature: Long femurs, short torso, very heavy weight load.

The long femur short torso person who accomplishes a squat does so at a few costs:

1) The lower back is forced to absorb tension that is supposed to be taken up by the glutes and legs, and 2) This type of body may learn to over-dorsiflex the ankles, putting undue stress on the knees.

So even though they can boast, “I have long femurs and a short torso but I can deep squat without rounding my back,” remember those two cost elements.

The lower back muscles (which stabilize the spine) are not designed for force production; the glutes, quads and hams are.

When forces are imposed on them that they are not designed to handle, the risk of a ruptured disk becomes higher, and what becomes even greater is a soft-tissue injury.

A person with short femurs and a long torso is capable of bad form in the squat, but this bad form can be corrected with a little practice.

For those with long femurs and short torso, they do not have the same choices.

Their long femurs throw their hips out so far as they lower into a squat, that to counterbalance this, they must lean their torso way forward.

Try this Experiment

Sit in chair that makes your thighs parallel. How far must you lean forward to get your shoulders over your ankles — while keeping a lower arch in your back? For many of you, it won’t be far; you may be virtually upright yet.

Now, imagine that several inches have been slashed from your torso. This displaces your shoulders back by several inches.

This forces you to lean forward MORE to get your shoulders above the ankles! The shorter your torso, the more you have to lean forward.

Or, the longer your femurs (which make the feet further from your center of gravity), the more you must lean the torso forward!

This situation is more prevalent in women. Look at a photo of a woman and man of equal height standing side by side.

Usually the woman’s waist is higher and her legs are longer. Though she may not have long femurs relative to her overall leg length, her femurs may still be longer than her short torso!

This puts her at a biomechanical disadvantage in the squat.

Though some women have visibly long torsos and stubby femurs, this is not the typical build of a woman.

View this video (hopefully it’s still up) of a man with long femurs and a short torso performing a back squat, and if you’re still a critic of this “excuse,” tell me how this man can get his back even a little more upright without falling backwards.

He’s already quite bent over early on in the squat, just to keep from falling backwards.

To the untrained eye, it appears that his form is poor, and I’ll admit, it can be improved despite his “levers.”

But look what he must do to get his shoulders over his feet.

Pause the video right when he gets into the deepest point of the squat.

Imagine him getting his back more upright. Note what would happen to the alignment of his shoulder over his feet; the imaginary vertical line between the two points would be shifted towards behind him at the top — which would send him pitching backwards to the floor!

He has no choice but to fold up to offset the distance his hips are from his knees as he squats.

A longer torso (or shorter femurs) would enable a more upright back, and hence a strong lower back arch.

I’m sure that the forum posters who criticize the long femur to short torso defense would never criticize the guy with the T-rex arms who says his deadlift bombs because of his short arms. Let’s face it: Anthropometrics can’t be ignored.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Why You Can’t Go Parallel with Barbell Squats or Even Bodyweight

If you can’t get parallel with squats and fall backwards instead or must hold something in front of you, you won’t like the reason.

Many things have been blamed for not being able to go parallel with squats (free barbell or bodyweight), and often, the most likely culprit gets overlooked.

If you struggle to reach parallel with free barbell or bodyweight squats, you may want to take a look at the length of your thigh relative to your shin. Are you “long thighed” or “short thighed”?

This relativity factor is NOT related to overall body height.

If when you wear shorts, you’re “all thighs,” chances are you have the so-called long femur.

A femur that seems too long for the shin is very likely longer than your torso, and therein lies the problem.

Long femur, short shin

When it comes to barbell or bodyweight squats, a long femur (thigh bone) is a biomechanical disadvantage, especially when paired with a short torso.

In fact, regardless of a person’s height or relative shin length, if their femurs are longer than their torso, this puts them at a disadvantage in the squat.

Many other variables have been blamed on being unable to go parallel with the squat:

Lack of flexibility in the ankles and hips

Weak anterior tibialis muscle (muscle in front of calve)

Stiff lower back; tight calves and poor form.

General weakness. An out-of-shape person, even with femur length shorter than torso length, will likely struggle and end up with bad form (rounded back, hunched shoulders, arms needing to be extending out front to prevent toppling backwards).

Though these are all legitimate reasons for difficulty in parallel squatting, they can also be corrected.

If your femurs are relatively long compared to your shins, coupled with a torso shorter than the femurs, you’re in big trouble.

To counteract the anatomical problem, what must you do?

Someone with poor anthropometrics for the squat must lean their torso very far forward — so far forward that they can lose the arch in their lower back that they’re supposed to have when doing the squat.

In these cases, the back is rounded, chest down. They aren’t in a squat; they are in a crouch.

But even if the back remains straight, it’s still leaned WAY too far forward.

To keep from falling backwards in the barbell squat when parallel, you must have the barbell positioned right over your ankles/midfoot.

To achieve this, the long-femur man or woman (especially with short shins) must really pitch forward to get that barbell over the ankle.

This forces the lower back muscles to absorb considerable tension, increasing injury risk to the lower back and subtracting workload from the quadriceps and glutes.

If a person has great flexibility at the junction of the shin and foot, as well as Achilles tendon flexibility, they could move their knees far ahead of their feet (increase bend in foot/shin junction), which would bring their hips (center of gravity) forward, to get the barbell over the ankles/midfoot.

This would enable him or her to keep balance without leaning their torso over so much.

However, there are several problems here.

1) The shin/foot/Achilles flexibility needs to be developed and may never be enough

2) The knees being so far ahead of the feet puts one in an inefficient position to handle heavy weight, since workload is shifted away from the butt and hamstrings and concentrated too much on the quadriceps, and

3) This positioning puts undue stress on the knees.

The inability to get the feet flat on the floor while in a parallel squat is typically blamed on “poor ankle flexibility.”

Check your femur-to-shin or femur-to-torso proportion; chances are extremely high that this is the problem with parallel squat difficulty.

Now, imagine someone, let’s call him Henry, with very short femurs and crazy long shins; exaggerate these features in your mind as you mentally illustrate the profile.

Henry lowers into a squat. Note how close his hips are to his knees while his thighs are parallel.

With his very long torso, note that Henry hardly has to lean forward to get the barbell over the midpoint of his feet.

The angle that’s created by Henry’s torso with his thighs is significantly bigger than the angle created by the long-femur, short-torso counterpart.

If Henry’s spine is long enough and femurs short enough, his back will be practically upright while he’s parallel in the squat.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Shutterstock/El Nariz

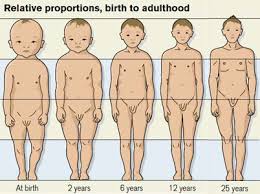

Why Young Children Squat Easier than Adults

Adults who can’t get parallel with a squat, let alone deep, must realize that one reason children squat so easily is body proportions.

Google “children squatting” and hit “images” and you’ll see toddlers in a very comfortable looking squat position, which makes adults envious who struggle or find it impossible to get into even a parallel position.

Look at the femur length of the toddler above, and compare it to his torso.

What do young children have, as far as natural squatting skills, that adults lack?

Just why IS it easier for children to squat than it is for adults?

If you’re seething with jealousy, it will be of some consolation to know that a lot of this has to do with the length of a child from head to hip, relative to their legs.

Anyone who’s been in the news loop only halfway has certainly read at least one story of a toddler drowning — as a result of tipping headfirst into a bucket of water or a toilet bowl.

The news article goes on to warn parents about this danger because toddlers are top-heavy.

Shutterstock/Nym_Pleydell

A report from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission states that between 1996 and 1999, 58 children under age 5 were reported to have drowned in five-gallon water buckets.

The CPSC report says that “…the stability of these buckets, makes it nearly impossible for top-heavy infants and toddlers to free themselves when they fall into the bucket headfirst.”

Toddlers have also fallen into toilets with tragic outcomes; the CPSC report adds, “The typical scenario involves a child under 3-years-old falling headfirst into the toilet.”

Bottom line: Young children are top-heavy.

This top-heaviness makes it easy for young children to do a full squat and maintain the position.

Shutterstock/savageultralight

Dreamstime/Pavel Losevsky

When adults do back squats with free barbells, the objective is to get the bar aligned vertically with the ankle/midfoot to keep balance.

Those with short torsos will have to lean forward more to do this, making the squat more difficult.

Long femurs add to the problem because the long thigh bones push the hips back, which in turn requires more leaning forward to get the bar over the mid foot.

If a person has a long torso, they don’t have to lean very far forward to align the bar with the foot.

A short legged (especially short-femur) adult with a long torso is a natural squatter; the long upper body lever allows them to stay closer to upright all the way into a deep squat.

So how does this relate to young children easily full squatting?

At birth, the head is one-fourth a baby’s height. In an adult, the head is about one-eighth the body height. This is Physics 101.

A toddler’s head is a big segment of their overall body length, and acts as opposition to the forces that want to pull the body backwards when in a squat.

Think of the young child’s head as the barbell in an overhead squat!

Adults who have difficulty with the parallel back squat will find that the overhead squat is easier, because the positioning of the barbell adds “length” to the upper body, increasing the lever arm, thus reducing the need to lean forward to align the bar with the feet!

A young child’s relatively big head is a built-in overhead bar! Any profile shot of a toddler or preschooler squatting clearly shows this.

In most adults, the head plus trunk make up about one-half the total height. In a baby, the head plus trunk make up five-eighths.

Though five-eighths is only slightly more than four-eighths (which is one-half), this slight difference is more than enough to yield a huge biomechanical advantage in full squatting! As children grow, these proportions shift.

Earlier I pointed out that an adult’s head is one-eighth their height, and a baby’s head is one-fourth.

For children 6.75 years, the head is between one-fifth and one-sixth their body height.

For an adult to have the squatting ease of young children, his head would have to be around one-fifth his height, with head plus trunk being five-eighths total height. You wouldn’t want to look this way.

To better understand the physics, imagine a toddler bending over, like an adult, to pick something off the floor. What would happen? They’d likely pitch headfirst into the floor.

Many other factors influence the ability to squat full and even parallel, including squatting facets, which are bone structures of the talus (ankle bone) and tibia (shin bone) that are adapted to squatting.

As Western peoples get older and eliminate squatting, the facets disappear.

Children are natural squatters, but the vast majority of Western children will lose this as adults.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Shutterstock/ Rozochka

Sources:

cpsc.gov/cpscpub/prerel/prhtml02/02169.html

dace.co.uk/proportion_child_2.htm

toilet-related-ailments.com/squatting-facets.html

Are Long Femurs a Good Excuse for Lousy Back Squat Technique?

Yes, long femurs DO really SCREW up the back squat!

It’s interesting that the men in fitness forums who slam those who insist their long femurs screw up their back squats don’t suffer from long femurs themselves — though they may think they do.

Whenever someone posts that their long femurs cause problems with the back squat, someone invariably posts that HE, too, has the very long femurs (e.g., “I’m 6-3 but go ATG without a problem!”)

The “long femur” in the strength training and powerlifting community refers to length of thigh RELATIVE to torso. It can be one of two ways:

1) Femur is longer than torso—and torso may be medium relative to body, or short, relative to body, but the bottom line is the femur is longer than the torso. OR…

2) Torso is same length as femur, but the problem is that the shin is too short, relative to length of femur. So even though femur-torso relationship is okay, the short shin creates the problem.

It can also refer to the length of the femur relative to the length of the shin (from knee to ankle). A “short shin” will impact the squat.

We are not all built the same.

We can’t all be built the same for the back squat yet built differently when it’s time to be fitted for a suit, or when adjusting the car seat angle plus its proximity to the pedals plus its height.

Ironically, these same critics will agree:

#1. Long, “ape-like” arms (relative to the body height) are a big disadvantage in bench pressing.

#2. Short, “T-rex” arms (relative to the body height) are a big disadvantage in the deadlift.

#3. Long “spider” arms will kill anyone’s chance at excelling with Olympic-style weightlifting.

Oddly, these critics slam the long femur excuse for a lousy back squat.

The difference in bench press and back squat body proportions is this:

No matter how “disadvantaged” the ape armed person is compared to the T-rex armed person, the “gorilla” can STILL bench press with perfect form and efficiency (though they’re at greater risk for rotator cuff strain). It’s just that they probably won’t win competitions.

In the case of the long femurs to regular torso, or the regular femurs to short torso, or long femurs to short torso, and especially relatively short shins tossed into this equation — these proportions get in the way with the ability to efficiently perform the back squat.

Such proportions force the athlete into a very bent-forward position, unlike the genetic freak below:

One must fight to keep his or her back in decent position, battling to keep it from rounding.

There is also ongoing tension in the entire vertebral column due to this awkward positioning of having to lean so far forward yet maintain the lower back ARCH.

Can bad proportions be offset by increasing one’s ankle, hip and knee flexibility?

To a small degree, yes. But there are limits to how far you can drive your knees over the ankles (though Olympic-style weightlifters are trained for significant dorsiflexion).

If the knee is too far over the toes, this puts strain on the knee joint.

Hips can only sink so far, too. These fine-tuning adjustments make a difference, but there’s no substitute for being born with great proportions!

Even if you developed amazing flexibility in the ankle, this fails to solve the bad biomechanics of longer femur to torso proportion, because the significant angling forward of the knees (due to extreme ankle flexibility) is akin to doing the back squat with one’s heels on a little platform!

That’s a lot of tension on the knee’s patellar tendon!

Imagine performing back squats while you’re on the balls of your feet.

Forget the balance issue. Instead, imagine how your knees would feel, going up and down this way with heavy weight across the back.

If your femurs exceed the length of your torso, you have a legitimate concern, especially with ATG (“ass to grass”).

Try the following adjustments:

1) Widen the stance; work on hip flexibility.

2) Slightly point feet outward (this naturally coincides with a wider stance).

3) Wear a one-inch heel insert, which produces the same effect as pricey lifting shoes.

If these adjustments fail, the back squat just isn’t your thing; focus on other leg exercises (split squats, dumbbell squats, box squats). On the flip side, long femurs are an advantage in kickboxing!

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

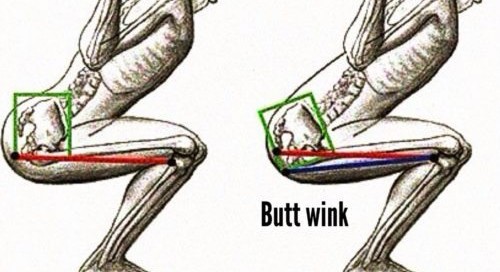

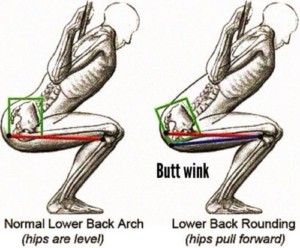

Why the Squat Butt Wink Is Bad & Why It Needs to Go

The so-called butt wink in a back squat is bad news and if you have this problem, it needs to be corrected.

Many people butt wink when they perform a squat. Many don’t realize they do this. Why is the butt wink a bad thing?

Well, look at someone doing this. What do you see?

A butt wink is when the lower back loses its extension and morphs into rounding, as the person lowers deeper into the squat.

Some people do the butt wink right before they bottom out, while others experience it a little bit before they reach their depth (whether that’s parallel femurs or deeper).

The butt wink is not deliberate or intentional. It just happens, and there are varying explanations.

How many times have you heard, “Never round the lower back,” when it comes to the squat? Yet, the butt wink is precisely that.

So what’s so bad about a rounded lower back in the squat exercise?

Plenty. The lower back (erector spinae) muscles are stabilizers. They are not force-production muscles.

Their job is to stabilize the spine and transfer forces from the upper body to the lower body, not move heavy weight.

This is why low back injury can result when someone lifts a heavy item off the ground while their lower back is rounded, trunk flexed forward.

The erector spinae are not supposed to absorb forces that the legs and glutes are supposed to absorb.

When a person is at the bottom of a squat, in a butt wink, the erector spinae muscles are absorbing forces that they shouldn’t be, even though the man or woman may not feel this occurring.

When they begin rising out of the squat, the butt will “unwink.” In order for this to happen, the low back muscles must engage before the legs and glutes do.

Once the low back is returned to an extended (arched) position, the legs and glutes can take over.

The risk of low vertebral injury increases as the weight load increases. A “rounded back” during a squat doesn’t always have to resemble the Hunchback of Notre Dame’s.

- Watch someone butt winking.

- It can be quite subtle, but when it’s there, even a half-trained eye can detect it.

- It doesn’t look right, and there’s a reason for that; it’s not right.

Though the increased risk of low back injury is slight if the load isn’t that heavy, who needs strain in this region?

The risk is higher in people who already have tweaky erector spinae muscles.

The butt wink is bad. Make a concerted effort to kick this problem once and for all.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Long Femurs: Why Wide Stance Makes Parallel Squats Easier

This article explains in plain English the fascinating reason why a wide stance makes squatting parallel so much easier for long femurs.

If you know that long femurs have been hampering your ability to go parallel in a squat, you’ve probably figured out at some point or have been told or read that a wide stance will correct the problem.

I’m a former personal trainer…but…I also have long femurs relative to my shin length, which causes the same issue as femurs exceeding the torso length.

To understand why a wide stance makes the parallel squat so much easier for those with long femurs, it’s important to know why a long femur creates an obstacle to squatting parallel.

NOTE: When I say “long femur,” this refers to relative thigh bone length to the rest of the leg, and has absolutely nothing to do with a person’s height!

A person who has a long thigh and short shin has a long femur, even though they may stand only 5-5.

As one descends into a squat, the hips get pushed out further away from the foot in terms of horizontal distance.

Shutterstock/IvanRiver

In order to keep balance, there must be a vertical line between the ankle/midfoot and behind the shoulders.

As you lower into a squat, this vertical line must be maintained or you’ll fall backwards.

To maintain this vertical line, you lean your torso forward, to bring the shoulder over the ankle/midfoot.

If you don’t lean over far enough, you’ll start falling backwards. You don’t want to lean more forward than you have to.

The more forward you lean, the more that the parallel squat becomes a low back exercise.

If you have long femurs, your hips will be pushed back far from that imaginary vertical line that extends up from the ankle/midfoot.

To counteract this, you must lean the torso in more than if you had short thigh bones.

If your femurs are long enough (again, this is relative to overall leg length and is not related to height), you will need to lean the torso over so far that it’s approaching parallel to the floor. This is an incorrect squat position.

Imagine a barbell across your upper back while your torso is parallel to the floor while you’re squatting parallel. This is not a back squat. It looks more like the good-morning exercise — shown below.

Everkinetic.com

The reason someone with long femurs can’t squat parallel while maintaining even a 45 degree torso lean is because even at this much of a lean, the back of his shoulders still does not meet up with that imaginary vertical line.

It’s “behind” it, because the long femurs have his hips pushed out so far.

Why does a wide stance make parallel squats easier?

Freepik

The wide stance makes squatting parallel possible without having to pitch the torso forward like a good-morning exercise.

In fact, the wide stance can enable someone with long femurs to be quite upright; if the stance is wide enough, feet pointed out, one’s spine can actually be vertical.

But as the stance widens, the muscle recruitment changes.

When the stance is wide, the horizontal distance from hips to knees is shortened. This mimics a short femur.

Even though the knees are displaced outward, it’s that horizontal or forward distance between hips and knees that makes the difference.

The body now “thinks” it has short femurs!

The hips, then, aren’t thrust out so far behind the person.

Thus, he does not need to lean his torso over so much to align the back of his shoulder (where a barbell would go in a back squat) with his ankle/midfoot.

If the wide stance is uncomfortable on the knees, angle the feet out enough to relieve the discomfort.

If the stance is wide enough (especially with feet pointed out), the adductor (inner thigh) muscles will absorb considerable tension.

Stiff hips will make a very wide stance uncomfortable. Good hip flexibility is a must.

Go only as wide as necessary to maintain a parallel squat unless you want more adductor focus.

If long femurs are a problem with doing a parallel squat, widen your stance and see what happens.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Shutterstock/LightField Studios

Why You Shouldn’t Compare Adult’s Squat with Child’s Squat

There is no comparison between an adult’s full squat and a young child’s full squat, yet people continue comparing the two when discussing the back squat exercise.

As a former personal trainer, it continues to amaze me at how often other personal trainers and hardcore strength training and weightlifting enthusiasts keep pointing out that if a young child or toddler could get down into a full squat, an adult should be able to do so. Bah!

Any layperson with his eyes half open should be able to see a more-than-subtle difference between a toddler’s, and even grade schooler’s, body proportions, and an adult’s, even a short adult’s.

The distance between a toddler’s hips and head, relative to their legs, is significantly greater than in an adult’s!

View a profile of a toddler in a full squat. The relatively huge head of the child below prevents him from falling backwards and provides a comfortable leverage point.

Shutterstock/Rozochka

The length between the toddler’s hips and head acts as a fabulous leveraging device that easily keeps the baby (or young child) from falling backwards, while allowing the toddler to keep his back fairly upright.

To keep from falling backwards, a person in a deep squat needs to have the shoulders vertically aligned with the midfoot.

The less length between the hips and the shoulders, the more that the person needs to lean their torso forward, to get the shoulders smack over the midfoot.

This fact of physics is SO obvious, I don’t know why it escapes so many fitness professionals and gym enthusiasts.

A young child squats to retrieve something on the floor or work with something on the ground.

Instinctively a toddler knows that if he bends over like an adult, he’ll fall flat on his head.

Toddlers and babies are top-heavy enough to tip headfirst into a bucket of water and drown; they can’t lift themselves out because there’s not enough “length” under their center of gravity to straighten back up.

A report from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission states: “…the stability of these buckets, makes it nearly impossible for top-heavy infants and toddlers to free themselves when they fall into the bucket headfirst.”

I’ve read the strength training and muscle building forums, and time and time again, someone points out that if toddlers can full squat, adults can, once they stop making excuses.

Now, I’m not endorsing any excuses here. My criticism is the comparison of adult full squats to children’s full squats (also known as the Third World squat).

I might also mention that the full squat of a toddler is entirely different from the classic Third World squat, which is more of a crouch, though in some nations, an adult version of the toddler full squat is commonly used as a resting position.

Another reason the child’s squat to adult’s is an unfair comparison is because toddlers have ridiculously short femurs relative to their shins.

This is SO evident in early toddler-hood, when babies are walking across a room just in their diapers, and all you see are these shins coming out of the diaper; where are their thighs (femurs)?

The femur gets longer, relative to the rest of the body, as the child grows, but for quite a while, that femur is this short stumpy thing that provides superb leverage in a full squat, keeping the shoulders easily aligned over the midfoot because the minimal hip displacement by the super short femur minimizes the forward torso lean.

An adult’s head is one-eighth their height, on average. An infant’s is one-fourth their body length!

Though a toddler has grown quite a bit since being born, his head is nowhere near one-eighth his body length!

That big bobbing head of a toddler serves as an excellent counterforce to the mild hip displacement in a full squat!

Older children, too, have this advantage, but not as pronounced, but enough to make a comparison between even an older child’s full squat and an adult’s full squat outright ridiculous.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Top image: Freepik.com

Sources:

cpsc.gov/cpscpub/prerel/prhtml02/02169.html

www.dace.co.uk/proportion_child_2.htm

Short vs. Long Femurs for Hiking

Does femur length really matter when it comes to hiking efficiency?

“Long femurs” refers to relative length of these bones to one’s overall height or leg length, and in the world of weightlifting, the issue of long femurs becomes relevant when these bones are longer than one’s torso.

A person can stand only 5-5 and have long femurs. A person can be 6-2 and have short femurs, meaning, for their height or leg length, their thighs are pretty short — they have an endless shin bone.

Long femurs are a biomechanical disadvantage in the barbell squat exercise, but an advantage in cycling due to torque (measure of force on a rotational object).

Short femurs are a big advantage for squatting, but a disadvantage in cycling.

So what about hiking?

Hiking includes descents. For hiking, long femurs come out ahead of short thighs, and remember, this is all relative to one’s overall height.

So don’t assume that every tall person has long femurs and every short athlete has stubby thighs.

Geoffrey Mutai is an elite marathon runner who has long femurs relative to his shins and overall height:

I have long femurs and stand 5-8. I finally figured out why I seem to be the only person in a group hike who can effortlessly and quickly ambulate down a talus slope.

I’ve always thought it was related to my years of playing volleyball (lots of “getting low” and “staying low”). I now think that long femurs have something to do with this.

To prevent falling on a talus slope (or any hill while descending), the hiker needs to get their center of gravity as close to the slope as possible.

This is why a dachshund has an easier time ambulating down a steep hill jutting with rocks than does a greyhound.

Long femurs also conserve energy when the hiker ascends, and I’ll explain why in a moment.

Hiking down a steep hill and especially talus slope should be done while in at least a half-squat position.

A hiker with short femurs can drop their center of gravity only so much before unnatural hip flexibility is required to sink even lower.

To understand all this, visualize hikers with wildly exaggerated body proportions.

Let’s say that Polly has one-foot long femurs and three-foot long shins. Sally has the opposite: three-foot long femurs and one-foot long shins. Both women are the same height.

Imagine Polly carefully making her way down a talus slope, sinking her hips down as much as possible. She’s still far above the ground, what with those towering shins.

Her torso/back is upright, which is good. But her center of gravity is not very low. She is prone to being off-kilter, like the greyhound.

Furthermore, it takes more energy to create long strides down the slope, as her foot is extended way out ahead of her knee, and she must then thrust her hip forward to complete the stride, whether it’s a sideways stride or three-quarters frontal (which is how one should descend talus, by the way; never descend facing fully forward).

With long femurs, Sally can sink her center of gravity really low.

This is not the same as a conventional barbell squat, because efficiently descending on talus requires the knees and feet to be wide apart and pointed out for optimal control, thereby shortening the distance between knee and hip, allowing for a more upright torso position.

In fact, for maximal control over talus, the hiker’s legs should be very wide, descending sumo style; the sumo stance allows the hiker with long femurs to be upright.

But even if at times, the feet are closer together, making the hiker with long femurs lean forward, the forward lean is okay because there isn’t a barbell across the back!

Sally’s center of gravity, like a daschund, is close to the talus. If she steps on a loose rock and starts falling, she won’t have as far to fall as will Polly, whose hips, torso, arms and head are further up, even though the hikers are the same height.

Long femurs enable Sally to complete long strides without thrusting her hips towards the stepping foot.

Imagine her descending, hips close to the ground because she is more horizontally displaced due to the long femurs.

I will admit that hip flexibility plays a role here. If a hiker has stiff hips, they’ll be inefficient at descending in a squat, regardless of femur length.

All talus descents should be done in a squat, with feet placed wide, regardless of femur length.

The closer your center of gravity is to the slope, the less likely you’ll fall, and if you do fall, you’ll have less distance to fall.

When ascending, Sally’s long femurs will have an advantage in that she won’t have to execute as much hip flexion as will Polly.

Polly can still get the job done quite well if she’s physically fit, but from a biomechanical standpoint, Sally will use less energy because long femurs will allow her to climb with less range of motion (hip flexion).

Visualize their climbing profiles using exaggerated features again, and you’ll clearly see the biomechanics.

This is easier to visualize if you replace a hill with a staircase. Polly must lift her foot up higher to get it on the next step.

With long femurs, Sally doesn’t need to lift as high (less hip flexion, smaller range of motion, less energy expended). Plus, to push off from the step, Polly must use greater range of motion.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.

Sources:

(clear photo of Kagwe’s legs) http://forum.bodybuilding.com/showthread.php?t=138030823&page=1

marathonchamps.com/a-JohnKagwe.html

3 Exercises that’ll Improve the Back Squat for Long Femurs

Here are three simple and fun exercises to improve back squats if you have the unfortunate levers of relatively long femurs.

Bad levers do not mean that you can’t override long femurs by “strengthening your ancillaries.”

Three Exercises for Improving the Back Squat if You Have Long Femurs

Wall squat. Stand facing a wall and figure out the closest you can be to it before your knees would be touching when in a parallel squat.

You’ll need to hold onto something to get into a parallel squat to figure out the distance you need to be from the wall. Mark that distance (e.g., place yardstick parallel to wall).

Face wall and begin squatting, making sure that there’s something nearby you can hold onto.

The objective is not to let your head or face pitch into the wall, though it’s fine if your face (or side of) grazes it as you lower. You just don’t want to lose control and pitch forward.

You will notice several things:

1) This really forces your lower back to maintain an arch

2) It stretches the back of the lower leg/Achilles tendon, and

3) As you keep doing this, you’ll find you can eventually eliminate holding onto something with your hands, and instead just allow your palms to graze the wall.

With that third point, the arms can be straight but somewhere between horizontal and vertical, palms against wall.

The goal then would be to eliminate the grazing and not touch at all. Another goal is to sink as deep as possible.

You’ll notice that as you near the bottom, you’ll lose the lower back arch. This will happen to even a person with short femurs.

I don’t recommend going this far, because you want to teach your body to always have a low back arch.

Wall squats will force your body to get good at maintaining a low back arch past a parallel position.

As you improve with wall squats, stand a little closer to the wall. This will encourage less forward positioning of the knees, but realize that your proportions will have the final say-so.

The second exercise for improving the back squat if you have long femurs is what I call staircase squats.

Ideally, there’s a solid wall on either side of you. Even more ideally, you can sit on the steps where at least one of the walls ends and you can use that for support by curving your palm and fingers around it.

- Sit on a step.

- Position feet on the next step, as you would in a back squat.

- Place heels against the back of the step.

- Arch lower back and shift forward to get knees past the feet (maximize dorsiflexion in ankles).

Every time you begin this exercise, note if your shoulder is right over your midfoot.

This is key, because once you achieve this, you’re ready to remove your butt from the step — while keeping heels on it.

The beauty of this exercise is that you never have to worry about falling backwards. The wall allows you to use something for balance without gripping it.

The objective is to eliminate using the wall as you maintain the squat position, butt just a tiny bit off the step.

Hold the squat till you fatigue, then sit and rest. Repeat several times. Concentrate on maintaining the lower back arch.

Make sure feet don’t drift outward any more than you desire, as this can happen without you realizing it.

Working off the next step can be taxing, so alternate between that and the step after the next step.

In fact, beginners may want to use only the second step down, rather than the next step.

This exercise will increase dorsiflexion and train the lower back to keep the arch in those with the longest femurs.

The third exercise for improving the back squat if you have long femurs involves the stability ball, BUT it’s not what you think. There is NO wall involved.

Use a ball that when you sit on it, your femurs are either parallel or below parallel.

If femurs are above parallel, use a smaller ball.

- Position feet as you would in a back squat.

- Arch lower back.

- Align shoulders vertically with midfoot.

- Make sure you’re dorsiflexed as much as possible (never force dorsiflexion; just achieve your natural limit).

You are now in position for a back squat; because the shoulder and midfoot are aligned, you should be able to push the ball aside and hold this position.

Do that and hold until fatigue sets in. Rest and repeat several more times.

Those with long femurs will find that these exercises will enhance your ancillaries: the assistive parts of your body in a back squat. They are the 1) lower back, 2) ankles, 3) hips and 4) shins.

Long femurs + ancillary training + wide stance and you have it made!

When doing these exercises, always wear athletic footwear, and do not force anything or over-train because the tissue around the ankle joint can easily be overstretched.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Long Femur, Short Shin: Advantage in Leg Extension, Ham Curl

Though a long femur relative to shin is a disadvantage in squats, it’s a biomechanical plus in the leg extension and hamstring curl.

The long femur to short shin proportion has been vilified as bad levers for the squat and deadlift.

But it’s vital to point out that these “bad levers” are actually a biomechanical advantage for the leg extension and hamstring curl.

Let’s Look First at the Leg Extension

Shins appear LONG relative to femurs. Shutterstock/lunamarina

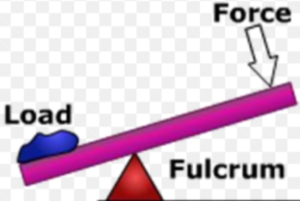

Many bodybuilders swear by this exercise for bringing out more sculpting in the quads. The fulcrum is the pivot point (in this case, the knee).

The resistance arm is the length between the knee and the foot where the foot is against the pad (weight application).

The force arm is the length between the knee and the hip.

The leg extension motion is similar to the classic example of a fulcrum and levers that we all learn in physics 101: the teeter totter, in which the fulcrum is represented as a triangle beneath the teeter totter.

On one end of the totter is a weight (the resistance). At the other end is the force (person pushing down on the board).

The closer the triangle (fulcrum) is to the weight, the easier it is to push down on the other end and lift the weight. Imagine the triangle very close to the weight.

That’s a very short resistance arm. Let’s say that the fulcrum is two feet from the weight, and the person at the other end is 15 feet from the fulcrum. He has an easy job.

Now move the triangle (fulcrum) so that it’s only two feet from the person and 15 feet from the weight.

The force arm is now only two feet, and the resistance arm is 15 feet. It will be extremely difficult to push the board down and move the weight.

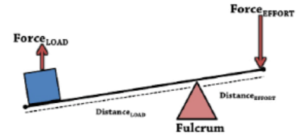

Apply these concepts to a person with a long femur and short shin, seated on a leg extension machine.

If the distance between knee (fulcrum) and hip is longer than the distance between knee and foot, this is akin to that triangle being closer to the weight.

In other words, think of the knee (fulcrum) as that triangle. Because the shin is short, the knee (triangle) is closer to the foot (weight application) than it is to the hip!

This becomes clearer when you imagine the athlete’s legs in full extension.

The knee is the fulcrum (triangle). If it’s closer to the weight application (foot) than it is to the hip (guy pushing down on teeter totter), it will be easier to move the weight!

Conversely, if the knee is closer to the hip (short femur, long shin), this is akin to the fulcrum (triangle) being closer to the guy pushing down on the board — making the work more difficult.

Imagine the profile of someone with a one foot femur and three foot shin sitting on the leg extension machine.

They begin extending their legs. That’s a LOT of shin bone that they must raise up, with that weight at the bottom (foot), and such a short force arm (short femur) to apply the effort.

Imagine a profile of someone with a super long femur and stumpy short shin. Gee, it’s pretty easy to get that shin parallel!

This same concept applies to the hamstring curl.

Shutterstock/Microgen

It will be harder for someone with short femurs and long shins to crank the weight towards their butt (short force arm) than it will for someone with a stretchy long femur and stubby short shin (short resistance arm).

So if you have long femurs and short shins, don’t despair over squat difficulties.

Do the best you can with the squat, but always include leg extensions and hamstring curls and see how much easier it is to move heavy loads than those with perfect squatting levers.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.