If a young able-bodied adult uses a walker out of fear of falling from dizzy spells, will this over time compromise her mobility and joint integrity?

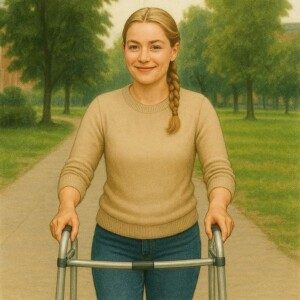

A woman I know uses a walker – she goes no place without it. However, she is able-bodied and only 29.

“Kelcie” says she has no difficulty walking (this is true; I’ve seen her walking very short distances without the device; her gait is normal and of typical speed, even though she’s morbidly obese).

She has reported she’s fallen a number of times around her house when not using the walker.

I take her out into the community; she has an intellectual disability and autism.

She’ll use the walker (she doesn’t lift it as she walks; she pushes it along the ground) even to go a short distance from a seat to a restroom.

The dizzy spells, which are sometimes accompanied by feeling faint, are allegedly from a migraine disorder that she’s been diagnosed with.

Kelcie doesn’t do any lower or upper body strength training or other exercise.

On the other hand, without the walker she’s at risk of falling from suddenly feeling dizzy or faint.

Why Using a Walker Too Long Can Backfire

Again, Kelcie uses a walker all the time to stay safe during unexpected migraines.

But over time, she could slowly be “training” her body to require the device, even if the dizziness goes away later.

A 2015 study (Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, Suica et al) looked at exactly what happens when healthy people use four-wheeled walkers (rollators).

They found that using the device dramatically lowered leg muscle activity — especially in the hips and thighs.

The walker took over part of the job their legs and core are supposed to do.

For instance, if you’ve ever used a walker, you’ll instantly note that natural workload is removed from your lower back. The soft tissue in this area will become weak over time.

Less muscle and supportive soft tissue engagement means these structures will get weaker as time marches on.

- Literally, Kelcie’s body will “forget” how to handle normal balance challenges.

- Always having the walker with her is not the solution to this forgetfulness!

The human balance system — our muscles, inner ear, eyes and neurons — works on a “use it or lose it” principle.

If we constantly lean on something for stability, our brain and body stop practicing quick balance reactions. I call this recalculation.

An example is one day I entered the vestibule of a diner upon exiting the place, and momentarily turned to look at the person I was with behind me.

In this process my eyes missed the bunched up rug just ahead of me and I tripped!

But lo and behold, my workout-trained neuromuscular system quickly recalculated, preventing a face-plant into the door just ahead of me.

I went from pitching forward to suddenly being upright again: fully recalculated.

A 2022 review (Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, McCrum et al) sums it up perfectly:

To keep your balance reflexes sharp, you must challenge them.

People who train with small, unexpected balance challenges (what researchers call “perturbation based balance training”) will get better at recovering from slips and stumbles.

An example of this training would be “rough walking” – at least twice a month, briskly walking on terrain that constantly changes in pitch, such as a big field at a park with its unpredictable lumpy areas or a level hiking trail (doesn’t even have to be inclined).

People who never experience those little wobbles lose that skill.

So if Kelcie, and anyone else who overuses a walker, prevents every tiny balance correction, her body won’t get the practice reps it needs.

If the migraine episodes eventually diminish and she ditches the walker cold turkey, she might find that her legs feel weak while at the mall, that her posture feels off, and her balance is wonky – all due to disuse.

The Might of Rehab and Strength Training

Charles Hall et al. published a big review (Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy, 2016 and 2021) showing that vestibular (inner ear) rehabilitation therapy retrains the brain and balance system.

Strength training can protect Kelcie’s muscles from weakening.

A 2022 systematic review by O’Bryan et al. found that moving gradually heavier loads over time rebuilds strength and prevents atrophy.

We must also recognize that the longer the time passage of using a walker, the more challenging it’ll be to regain lost use through any form of rehab.

Suppose at 35 Kelcie ditches the walker. With proper training she can restore normal lower body and core function.

But what if she doesn’t ditch it until she’s 55? The outlook won’t be as promising – even with balance retraining. The body ages. We can’t get away from this fact!

Nevertheless, that perturbation based balance training that was mentioned earlier can still prove quite useful (Gerards et al., Age and Ageing, 2023; and Nørgaard et al., BMJ Open, 2024).

PBBT involves drills where the body must react to small pushes or shifts, improving how fast you can recalculate a slip or stumble.

Use of a walker outright prevents the body from the PBBT that naturally and randomly occurs in the ambulation of daily existence.

So then what, take away the walker and let her keep falling?

If the device becomes the only way Kelcie walks, year after year, it can lead to the very weakness and instability she’s trying to avoid.

Nobody’s saying she must abandon the walker.

But heavens, she absolutely NEEDS to be on a strength training program!

Her parents, neither of whom have ever been into working out or fitness, are fully accepting of this walker lifestyle and have not made aggressive attempts to counteract its adverse effects – or at least, the ones down the road as Kelcie gets older.

A basic program of squats (no, not barbell squats, but reasonable-type squat variations for a morbidly obese, sedentary individual), lunges, heel raises and core work — done consistently, will keep the legs and trunk strong (O’Bryan et al., 2022; Lopez et al., 2020).

There’s actually so much Kelcie can do for her legs, and she has plenty of time, as she doesn’t have a job.

But her parents haven’t made fitness and strength training a priority, and are content with her very sedentary lifestyle of day programs.

Kelcie doesn’t even do simple balance exercises, such as standing on variable surfaces or walking backwards or side to side (McCrum et al., 2022).

As a former personal trainer, I’ve had clients of various challenges do all sorts of lower body and core work that resulted in significant improvements. This doesn’t require capturing the moon!

Final Thoughts

Long-term, exclusive walker use can slowly make your legs weaker and balance less reactive, especially in someone young who has decades of mobility ahead.

Kelcie isn’t unique; it stands to reason that there are many others out there who use a walker for similar reasons, who have nothing wrong (yet) with their legs or mobility.

I also can’t help but think that her parents’ lack of concern over continuous walker use is related to the phenomenon of overprotecting a child with the duo diagnosis of ID and autism.

The evidence clearly says that with the right combination of vestibular therapy, progressive strengthening and balance training can help Kelcie stay strong, steady and eventually walk confidently again should an effective treatment be found for her dizziness and faintness episodes.

There’s also the option of keeping the walker off the ground a few inches when “using” it, to allow the body full participation in ambulation, thereby preventing any of the aforementioned problems.

If a fainting feeling or vertigo come on, the patient can easily put the walker to the ground, it having been only a few inches off it to begin with.

This strategy would need to be discussed with the individual’s physician.

![]()