The neurotypical child got increasingly frustrated when the autistic boy stopped answering her repetitive question at a playground. They were strangers.

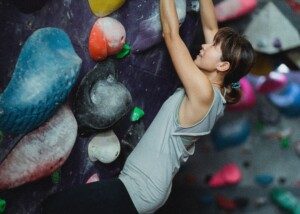

He was six and enjoying the climbing equipment by himself. The little girl came out of nowhere and began asking him questions.

The first two were basic: What was his name, and did he like climbing. But as the questions became more involved, he became quiet.

The neurotypical young child asked the same question three times, showing frustration that the boy – whom she didn’t know was autistic – was not responding.

She probably didn’t even know what autism is.

But one thing’s for sure. This neurotypical child failed to read the boy’s body language that he was not interested in fraternizing with this stranger and would rather just continue playing on the climbing structure.

The girl had persisted, unable to recognize the blatant cue of “I’m not here to talk to strangers; I’m here to climb; leave me be already.”

This scene actually happened, and I’ll get to more details in a moment.

But first, it’s crucial to acknowledge the unfortunate truth that we live in a society where autistic people are considered the social oddballs.

This supposedly normal girl was clueless about basic manners: When it seems a stranger at a playground isn’t interested in chatting with you, then back off instead of asking the same question three times.

One might say that, indeed, she was normal, but that the problem is her parents for not teaching her manners.

But shouldn’t the neurotypical brain have a built-in sensor that tells you when it’s time to back off, even as a child?

It’s not as though this girl was four. Presumably, she was close to the boy’s age of six.

The scene took place at a playground in New Jersey.

Dad took his two autistic sons to the playground. Everything was going smoothly until the little stranger approached his younger boy.

Child psychologists would agree that what the girl did was normal social behavior – at least at first.

That she didn’t get the memo when the boy stopped responding is suspicious for either learned pushy behavior from her mother, or, she’s what we Autistics brand “hypersocial.”

The story has an aggravating ending, according to the dad who wrote about it on the New Jersey 101.5 site.

Dad writes: “I gently told her it was nothing personal, but my boy has autism so he might not answer everything.”

Cue the judgmental, ignorant and entitled mom of the girl who, writes the father, “blurted it out, ‘That’s it; come on! We have to go. Let’s go right now!’”

Way to go, Mums, sending the message that kids with different-working brains need to be avoided like the plague.

The author continues: I’ve had this happen several times; it’s shocking how some parents act as if autism is contagious.

“He Has Autism”

What’s intriguing here is that not every child on a playground who’s not interested in some stranger asking them questions is going to be on the Autism Spectrum.

I can easily envision a neurotypical little boy wanting nothing to do with some girl he’s never seen before while he contemplates his next climbing maneuver.

Not even every neurotypical wants to chitchat with a stranger.

In fact, Dad didn’t even have to disclose the autism; he could’ve just said, “He likes climbing so much he just wants to focus on that right now; that’s why he’s not answering your questions.”

Had the mother heard this instead, would her reaction have been the same? Likely not.

On the other hand, she may have still responded in an entitled way, believing that her daughter was so special that something must clearly be wrong with ANY child who doesn’t want to stop what he’s doing on a playground to engage with her.

She might’ve said to Dad, “Gee, you don’t have to be so rude.”

But when she heard “autism,” that scared her off.

If you’ve experienced a situation similar to what the author describes, perhaps have your child wear a headset to make it appear like they’re listening to music: a good excuse for not wanting to give much notice to a stranger.

If it comes to you feeling you must disclose the autism, I recommend phrasing it in a way that doesn’t sound like it’s an affliction.

If that girl had never heard of autism, it’s possible she thought the boy had a disease, being that Dad said, “He has autism.”

To a very young mind, that does sound like some sort of malady, being phrased that way.

Instead, say, “He’s autistic.” There’s a slim chance the other kid might think this is some kind of variation of “artistic.”

When I was very young and heard “autistic” for the first time (the voice on the TV said a child, being shown, was autistic), I believed it meant a type of artistic.

I myself was always drawing as a child, and “autistic” sounded so much like “artistic” that I thought they were related.

Another way to make the diagnosis sound less contagious is: “She’s on the Autism Spectrum.” This eliminates the phrase sounding like a disease, especially if spoken with a smile.

What if the stranger asks what it means? Just say, “It’s a different way of thinking and seeing the world.” Then leave it at that.

A very young child probably won’t press for a deeper answer.

An older child will likely have already heard the words autistic and autism and be satisfied with your answer.

But what if they keep asking questions?

Make this a teaching moment for them. Answer their questions. Keep your responses in small doses. I recommend avoiding saying, “God made him this way.”

This is a common line that kids get when inquiring about someone with a very visible disability.

It’s an easy way out for adults who don’t want to turn curiosity into an educational moment.

And many kids won’t buy it, either. Instead, this response will reinforce the idea that people who are “different” are to be avoided.

To bring the most powerful being in the universe into the fold is to make an innocently curious child think, “Wow, something must REALLY be wrong with him!”

Don’t give a patronizing answer. Be honest and real and state the truth: “She thinks and sees the world in a way that gives her many strengths, while also in a way that can be challenging at times, but I wouldn’t have it any other way!”

Here is the full article.

![]()