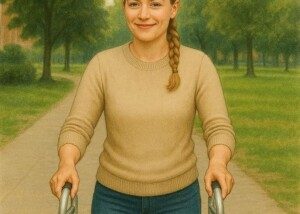

I’ve written about a woman who uses a walker everywhere “in case” she gets dizzy, despite no orthopedic need; this will harm her eventually.

This extensive use of a walker, in which the device is in continuous contact with the floor or outdoor ground, is “teaching” her body to forget to use all the muscles it’s supposed to use with unsupported ambulation.

My first article on this topic explains why such use, long-term, can damage her body, and what can be done to offset the harm of excessive walker use in someone with normal-functioning legs.

But let’s suppose “Kelcie” starts using the walker in a pre-emptive fashion: keeping it slightly off the ground.

This would mean “carrying” the walker in a non-weight-bearing manner for precautionary support in case of sudden severe dizziness from her migraine disorder.

Walkers are very lightweight. Holding one so that its legs are only a few inches off the floor or outside ground would not pose any strain on the upper body as long as the person remains upright rather than leaning forward while carrying the device.

By using the walker this way – ready to place it in contact with the floor in case of sudden severe dizziness – would still allow for normal ambulation and the weight-bearing that our bodies are supposed to conduct.

Kelcie has an intellectual disability; as a direct support professional I take her into the community a few times a week.

That walker comes with her everywhere, even for short trips from a table to a diner’s restroom.

Kelcie has no structured exercise program. It looks as though eventually, bearing her weight on the walker will weaken her core and legs, and damage her body’s balance mechanism.

None of this has actually happened yet (or so it seems), simply because she’s only 30.

But years of walking from point A to point B this way will surely train the body to forget how to efficiently move. It’s just inevitable.

So I’ve been thinking that maybe Kelcie can use the walker in a non-weight-bearing way.

The device would still be right there, good and ready to go, should she suddenly need it to support herself when a migraine episode occurs.

But I won’t suggest this, because it’d be beyond my scope of work to make this recommendation. In fact, as only her community connector, I can’t say anything about this topic.

If I ever meet her mother, I most certainly will introduce the topic.

Until then, I’m perplexed as to why her mother would not insist on a non-weight-bearing approach, as this would preserve normal ambulatory function and core strength!

The “Hovering” Approach to Using a Walker

Using a walker in a non-weight-bearing way might look unusual, but it can actually be really helpful for people prone to sudden dizziness.

Even if someone doesn’t need the walker to support their full body weight, having it in their hands can give a real sense of safety and confidence.

This precautionary use of a walker can allow for a rapid response if a dizzy spell hits.

By holding the walker close instead of continuous ground contact, Kelcie (even with her mental age of eight years) can immediately plant it and regain balance and steady herself while the migraine is in effect.

A 2021 study in the Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy found that perceived safety can improve mobility and reduce avoidance behaviors.

People who are afraid of dizzy spells often limit their activity, which can lead to deconditioning and more balance problems.

Carrying a walker without touching the ground helps keep people moving while reducing anxiety.

If Kelcie were to start feeling unsteady, she could plant the walker for full support, and if everything feels fine, she can continue walking normally.

But she doesn’t use the device this smart way. Instead, all four legs are in constant contact – the sound alone gives this away. It’s not a quiet walker; it’s a rumbler (no tennis balls).

The only time she disconnects it from the ground is if she’s going up or down a curb or similar structure. Then it gets planted again.

Unfortunately, nobody has informed her that the fixed planting is not necessary.

Perhaps Kelcie has been led to believe that she’d be helpless without the constant contact.

Nobody seems to be looking out for her future mobility.

It’s apparently a case of “Feel dizzy at times? Use a walker at all times from now on. That way you won’t fall.”

And then the directive was just left at that, with zero consideration for what long-term, weight-bearing use could mean for her mobility as she gets older.

Is this really sound advice? Think about it.

If I were prone to dizzy spells, I’d actually NOT use a walker. Instead, I’d be sure that my entire body was fit enough to promptly and efficaciously respond in the event of sudden vertigo.

If I were to begin using a walker, with continous contact on the floor and outside ground, every place I walked — and ceased all of my lower body workouts — you can bet that within 12 months I would have lost significant fitness and balance, plus acquired compromised mobility.

And that’s exactly where Kelcie — and anyone who bears their weight on a walker all day long to combat dizzy spells — is headed.

At least try hovering the walker! Give it a go for shorter walking segments, and then expand it from there.

I have a history of BPPV: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

I once had rapid onset of severe vertigo for which I didn’t feel safe ambulating about the house, so I stayed in a chair as much as possible.

But when I had to move from one room to the other, I was on high alert for a “recalculation” or swift balance check should I begin toppling to the side.

Without a walker, I simply moved steadily and slowly, knowing my core, hip joints, leg muscles, knee joints and feet were strong and efficient.

This is the ableness that Kelcie and anyone in the same boat should be trained to achieve!

My first article on this fascinating topic explains in detail just how damaging chronic walker use can be for an otherwise able-bodied individual.

As mentioned, it’d be beyond my scope of work to suggest to Kelcie herself that she hover the walker. I must bite my tongue!

But rest assured, if I ever meet her mother, it’s going to be one of the first things out of my mouth.

![]()