Also known as the “Aspie stare,” this doesn’t mean we’re having some kind of abnormal mental situation.

I’ve been executing the “Aspie stare” or “autistic stare” since childhood. Only I never thought anything of it.

I never thought it meant autism or anything neurodevelopmentally different or some deviation from the norm.

No; it was just something that suddenly came on and ran its brief, uneventful course.

If anyone had ever observed me in the midst of an autistic stare, they might’ve thought I was spacing out, zoning out, checking out or lost in myself or in another world.

When someone with ASD is staring off into space, seemingly for no reason, here’s what might be happening — based on my own experiences with this lifelong phenomenon.

First of all, I can’t bring it on at will. It just happens. It lasts 30 seconds to maybe two minutes.

As a child, my eyes would just suddenly want to sit still and do nothing.

You’d think I’d just close them at this point. But they didn’t want to close.

It was as though something made them become fixed in a random line of vision.

They’d be on whatever inanimate object just happened to be in that line of vision.

And something kept them there; they couldn’t be pulled away.

But I wasn’t inspecting whatever object my eyes just happened to have settled on.

I knew what the object was because I was seeing it. But I wasn’t interested in it.

My eyes just didn’t want to move, as though my eyes and brain wanted to just be idle for some moments.

Perhaps a reset was needed, and this was how it was done.

As the “staring” went on, my visual field would eventually start blurring.

At this point I’d be able to pull my eyes off the object, fully reset and resume whatever I’d been doing.

This phenomenon happened every so often since grade school, into my teen years and then into adulthood.

It still happens, although the blur-out doesn’t occur. I don’t recall when that stopped.

Almost always these days, when I yield this stare that probably looks quite blank to anyone who notices, it’s between weightlifting sets at the gym.

It may appear as though I’m in a trance or totally checked out. But I’m fully aware — just as I’d been in childhood.

I could still hear whatever’s going on around me. It’s just that something makes my eyes become idle and immobilized.

However, while this is happening at the gym, I’m counting seconds inside my head since the rest in between sets is based on time passage.

If my eyes are still parked on some object ahead of myself, and my rest time is up, I’ll “snap” out of it and resume my set.

If not, the staring will run its course before my rest time is up.

I may also go into this staring mode while waiting for a dentist visit or some other appointment.

I’m just sitting there in the waiting area, when suddenly I take to situating my vision on whatever object is in my field and parking there.

I’m pretty sure that if anyone notices this, they’ll see either blankness in my eyes or some kind of intensity.

When I’m engaged in the “Aspie stare,” my eyes don’t feel as they normally do. This is why I believe they look blank or intense.

As I type this, I have no recollection of anyone ever pointing this out to me.

The one thing I must make note of is that no matter how blank, lost or zoned out an Autist appears when conducting one of these stares, it is definitely NOT indicative of their level of self-sufficiency.

This phenomenon can be deceiving to those who don’t know the Autist.

It’s not an indication of anything “mental” or haywire. It’s just something that happens and runs its brief course.

Another Autistic Describes Their Blank Stare Mode

Jess Owen is co-creator of thewyrdsisters.co.uk with her sisters and was diagnosed with ASD at 25.

She explains, “As for the blank staring, sometimes my vision will go blurry, and I’m aware it’s happening and how to stop it — but I sort of just … don’t.

“I’m quite happy in a blurry little world where I can’t fully see what’s around me, at least for a minute or two.

“I remember enjoying the way lights looked through my blurred vision, which I believe is a form of stimming.”

Jess Owen, along with her sisters Emily and Abi, run thewyrdsisters.co.uk, about autistic sisters navigating a neurotypical world. Their goal is to spread information and awareness, and open up a conversation about neurodiversity that will make life easier for everyone.

Jess Owen, along with her sisters Emily and Abi, run thewyrdsisters.co.uk, about autistic sisters navigating a neurotypical world. Their goal is to spread information and awareness, and open up a conversation about neurodiversity that will make life easier for everyone.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

.

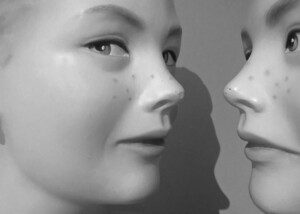

Top image: Freepik.com/master1305

Autistic Special Interest vs. Neurotypical Hobby: the Difference?