Lung cancer is one of the most terrifying cancers, one reason being that removing both entire lungs is never an option.

It’s hard to treat which is why the five-year survival rate is only 19 percent – the average when all stages of initial diagnosis are considered.

All lung cancer patients will get a treatment regimen, but the collective prognosis is bleak.

“It’s all about the stage of disease when patients are diagnosed,” says Alex Little, MD, a thoracic surgeon with a special interest in esophageal and lung cancer.

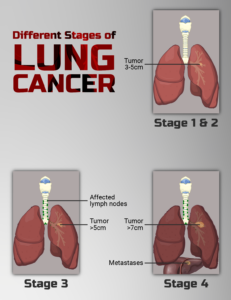

Dr. Little explains, “Roughly about 75% of patients present at initial diagnosis with stage IV (they have metastatic disease) or stage III (regional lymph nodes are involved) disease.

“Few of these patients will be cured, and I think the survival at five years is nearly zero.

“That means only a quarter of patients at diagnosis are in stage I, and are candidates for curative surgery.

“The five-year survival for these patients after surgery is about 80%. I’ve not checked all these numbers but they are reasonably accurate and would result in a five-year survival of all patients of about 19%.”

How Lung Cancer Is Treated for Different Stages – and Why It’s Difficult to Treat for Later Stages

“The challenge is to identify the patients for whom an operation is appropriate and then performing the appropriate procedure,” says Dr. Little.

“There are two aspects to this: staging the cancer and evaluating the patient’s status.

“Staging is the process by which the extent of the cancer is determined. The only reason to operate for lung cancer is the expectation that ALL the malignancy can be removed.

“If any is left—in the lung, lymph nodes or a metastatic site—the cancer will recur and the patient will not have been helped.

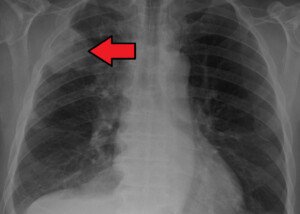

“Staging methods—not all are necessary in all patients—include taking a thorough history, performing a physical exam and using a battery of radiologic exams including a chest X-ray, chest computerized axial tomograph (CAT) scan, MRI scan, PET scan and biopsy of lymph nodes.

“A patient with lung cancer remaining after an operation will die of the cancer.

“But, if they respond to any combination of radiation, chemotherapy, immune enhancement or checkpoint inhibitors, they may live several years.”

You might be thinking, “Only several years? Why not 10 or even 20 years?”

It just doesn’t work this way. And nobody knows how far into the future an effective treatment will finally be developed – a treatment so effective that when a person gets the diagnosis of even late-stage lung cancer, the prognosis will be excellent – without losing any parts of their lungs.

Staging Results

“If all cancer is in the lung—no metastases and no spread to lymph nodes—an operation is potentially curative,” says Dr. Little.

The disease may be found in an early stage by accident when someone gets a chest X-ray for an unrelated reason, such as to check for internal damage after a car crash or for chest pain.

“If metastatic disease is found in a distant organ (liver, brain and bone are the most common locations), there is no role for surgery, as all cancer cannot be removed,” continues Dr. Little.

“If there are no metastases, and no lymph nodes are involved, but the tumor is invading the inside of the chest wall (most commonly at the lung apex, called a Pancoast tumor), an operation encompassing the lung and a segment of the chest is potentially curative.

“If there are no metastases, but lymph nodes in the area are involved, multimodality therapy is initiated.

“The patient receives a combination of both radiation and chemotherapy. If the tumor and the lymph nodes respond with dramatic shrinkage, then surgery is added for potential cure.”

Patient Status

The overall health of the patient, prior to treatment, can make treatment success difficult to achieve.

“Patients must be fit enough to tolerate/survive a lung resection,” says Dr. Little. “As most were/are smokers, organs damaged by smoking [including the heart] are evaluated.

“The heart’s status is determined by the patient’s exercise tolerance and, if necessary, function is evaluated by scans and even angiography if necessary.

“Lung function is routinely evaluated by a battery of lung function studies which contrast the patient’s breathing parameters to normal values.

“These studies inform the surgeon how much lung can safely be removed and the patient both survive the operation and have sufficient breathing capacity to expect a reasonable quality of life.

“Depending on the results, the thoracic surgeon may feel an entire lung can be removed if necessary (a pneumonectomy), a lobe is safe to extirpate (a lobectomy, the most frequently performed operation), or only a segment is safe (a segmentectomy, removal of part of a lobe).

“Ongoing success in treating stage IV and III patients has lengthened lives, but cure of these patients is quite rare. So from a curative perspective, treatment is difficult.”

Alex Little, MD, trained in general and thoracic surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; has been active in national thoracic surgical societies as a speaker and participant, and served as president of the American College of Chest Physicians. He’s the author of “Cracking Chests: How Thoracic Surgery Got from Rocks to Sticks,” available on Amazon.

Alex Little, MD, trained in general and thoracic surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; has been active in national thoracic surgical societies as a speaker and participant, and served as president of the American College of Chest Physicians. He’s the author of “Cracking Chests: How Thoracic Surgery Got from Rocks to Sticks,” available on Amazon.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.