Lung cancer is now being routinely treated by removing only a partial portion of the affected lung rather than the entire lung.

This precise surgery has been shown to have the same survival rates as whole-lung removal.

At the time I was training in surgery in the ‘80s, the accepted treatment for breast cancer was a mastectomy: removal of the entire breast, the muscles of the chest wall and nearby lymph nodes.

It was heresy to suggest to a surgeon that a lesser operation would suffice.

So, while many women were cured by this extensive operation, the significant price they had to pay included not just the significant disfigurement, but time in the hospital recovering, pain and frequently swelling of the arm.

This paradigm of extensive resections held for operations performed for many other cancers.

Now, a limited resection, called a lumpectomy, is the standard for breast cancer surgery with the addition of some combination of radiation, chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

Following a lumpectomy the patient leaves the hospital earlier, suffers less pain, has no arm swelling and has minimal disfigurement.

Crucially, the likelihood of cure is the same or better than in the mastectomy era. This is precision surgery.

The appeal of this type of precision surgery is self-evident. The aim is to replace an extensive operation, removing all or most of an organ and its lymph nodes, with a “smaller operation” which preserves more of the organ and provides the same possibility of a curative outcome but with less morbidity and fewer complications.

Surgeons and medical oncologists, working together, have been able to bring this concept to the care of several types of cancer.

I identify the important role of medical oncology in this process as the use of neoadjuvant (treatment before an operation) and adjuvant (treatment after an operation) therapies which are essential contributions to the success of “smaller” operations done with precision.

Surgery for Lung Cancer

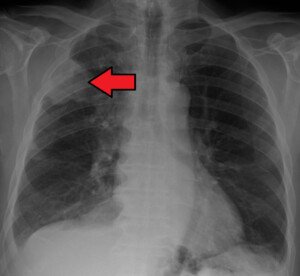

A similar scenario is taking place in my specialty of thoracic surgery.

The first operations for lung cancer were to remove the entire lung which harbored the carcinoma, an operation called a pneumonectomy.

This pattern followed the precedent set by the first pneumonectomy for lung cancer in 1933 by Evarts Graham, MD.

As I discuss in my book, “Cracking Chests: How Thoracic Surgery Got from Rocks to Sticks,” (written for the general reader, not physicians), this was a seminal precedent.

The patient not only survived, despite sufficient wariness to purchase a burial site before his operation, but was cured.

Loss of a lung removes approximately half the patient’s breathing capacity; the two lungs are not the same size.

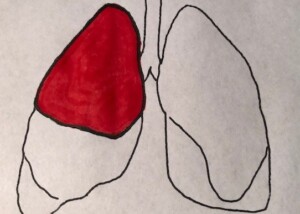

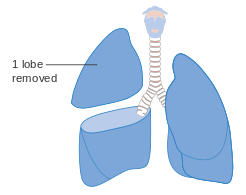

Appreciating the impact on the patient’s quality of life, thoracic surgeons developed techniques to allow a smaller, more precise, lung resection called a lobectomy: the removal of one of the lobes that are the constituents of each lung.

Cancer Research UK

A routine operation today, pioneer thoracic surgeons had to overcome technical challenges, discussed in my book, as performing this operation requires more tissue dissection than for a pneumonectomy.

This undertaking is required for precise identification and division of pulmonary arteries to and veins from the lobe as well as its bronchus (breathing tube).

Eventually lobectomy became the most frequently performed lung resection for cancer.

Occasionally a central tumor location mandated a pneumonectomy, the more extensive operation.

However, thoracic surgeons were reluctant to perform an operation that removed less than a lobe — as several studies have shown that this resulted in significantly reduced survival; the cancer tended to recur.

Although preserving more lung and pulmonary function than a pneumonectomy, a lobectomy does none-the-less result in the loss of between a third and a half of one lung.

So, there is still potential for improvement by becoming more precise, and surgical paradigms are changing as new information emerges.

Smaller than a Lobectomy

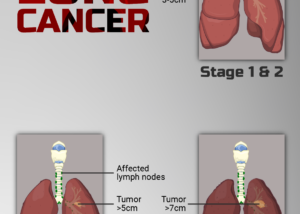

Several recent reports, including the results of a prospective, randomized study, show that operations smaller than lobectomy can be performed for certain lung cancers, resulting in preservation of functioning lung but no fall-off in the cure likelihood.

This should not be interpreted as implying this holds for all lung cancers.

The evidence shows that a smaller resection is a reasonable surgical choice when the tumor is relatively small and located near the lung’s periphery, and careful staging studies show no spread to lymph nodes or distant organs.

Lung cancer screening programs frequently detect these carcinomas.

There are two technical surgical alternatives as to how to perform this “lesser resection,” called segmentectomy and wedge resection.

Wedge resection of a lung. Chih-Hao Chen, Shih-Yi Lee, Ho Chang, Hung-Chang Liu, Chao-Hung Chen, Wen-Chien Huang, CC BY 2.0/creativecommons/Wikimedia Commons

The surgeon will select their choice based on their experience and the exact tumor location.

The full role of adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant therapy is not fully settled.

The Evolution of Lung Cancer Surgery

To give you some idea of how far lung surgery has come from earlier times, I close with a vignette from my book with a firsthand description of his actions from 1499 by an extraordinarily hesitant Italian “surgeon” named Rolandus, caring for an injured man.

“Called to a citizen of Bologna…I found a portion of the lung issued between two ribs…[and] it was not possible to reduce it.

“The compression exercised by the ribs, retained its nutrition from it, and it was so mortified that worms had developed in it…I, yielding to his prayers, and to those of his parents and his friends, and having obtained the leave of the Bishop, the master, and the man himself, I yielded to the solicitation of about 30 of my pupils, and…removed all the portion of the lung.”

The man survived, and thoracic lung surgery had taken a small, tentative step forward.

Alex Little, MD, trained in general and thoracic surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; has been active in national thoracic surgical societies as a speaker and participant, and served as president of the American College of Chest Physicians. He’s the author of “Cracking Chests: How Thoracic Surgery Got from Rocks to Sticks,” available on Amazon.

.