There are several mechanisms by which you can suffer acute liver failure as a result of your chronic heart failure.

The kidneys get virtually all of the attention in medical literature when it comes to organ damage secondary to heart failure.

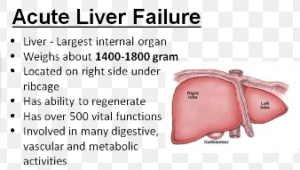

But the liver is smack in the war path of heart failure: both chronic and acute. Hepatic refers to the liver.

Strangely, there’s few papers in medical journals discussing the dynamics between the failing contractibility of heart muscle with liver perfusion (blood flow).

The liver is a greedy organ that siphons about 25 percent of the blood that the heart pumps out.

Common Sense 101 dictates that this amazing organ is highly sensitive to even slight reductions in blood supply.

Ejection Fraction and Heart Failure

“‘Sudden’ liver failure is usually called fulminant liver failure — where the bottom seems to fall out [figuratively speaking] and the liver fails, seemingly all of a sudden,” begins Mark Pool, MD, a board-certified cardiothoracic surgeon based in TX who’s been in private practice since 2011.

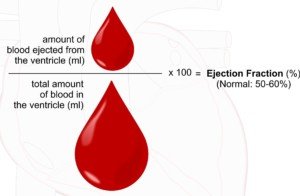

Ejection fraction refers to how much blood the heart pumps out with each contraction or squeeze. An ejection fraction under 50 percent is in the failure range.

Shutterstock/ellepigrafica

Severe heart failure is an ejection fraction under 30 percent, though there are degrees of severity within this advanced range of chronic heart failure.

So an ejection fraction of 25 percent is pretty lousy yet not what you’d call barely hanging on, but one of 15 percent is, for many patients, barely compatible with life.

Three Ways Heart Failure Can Cause Acute Liver Failure

#1. A patient’s congestive HF remains stable over the years, though gradually the ejection fraction is getting lower in small increments.

The poor liver — having for years been burdened with low perfusion (hypoperfusion) — has amazingly been able to compensate and keep the body going.

But at some point, the exhausted liver suddenly gives up its valiant fight and throws in the towel: acute failure … bringing with it classical symptoms such as jaundice, a puffy belly from fluid buildup, extreme weakness and even impaired mental status.

#2. Over time, hepatic oxygen delivery crosses a critical threshold due to yet one more incremental reduction in blood flow from a chronically declining ejection fraction.

The increment may be very small, not enough to show on an updated echocardiogram, but this newest reduction is the tipping point, sending the liver into acute failure.

#3. There’s a sudden bigger drop in ejection fraction (e.g., from 17 percent to 13 percent) over just days, and this is too much all at once for the liver to adapt to or compensate for, so it acutely fails.

Had this four percent EF reduction been evenly spread out over a much longer time period, say, six months, the liver would have compensated (at least for the time being).

So these three scenarios are quite plausible, says Dr. Pool, “and there may be some element of these phenomena in a lot of cases,” he adds.

However, these three pathogeneses, which can kind of be thought of as a cardio-hepatic syndrome, are not typical.

Dr. Pool says that acute liver failure “is uncommonly caused by heart failure.

But, I think of it as the patient may be teetering physiologically — the heart is barely hanging in there; the liver is barely hanging in there — and then, something happens.

“Maybe it’s a ‘cold’ or mild pneumonia or something like that. What a ‘normal’ person, or person without heart failure, would be able to shrug off and not be too affected by, now has a serious impact and can snowball into a major medical event.

“Just a ‘little bit worse’ heart function leads to a ‘little bit worse’ liver function, only now the liver function is not sufficient, and liver failure results.”

Syndromes

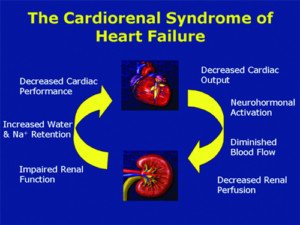

You’ve probably heard of cardiorenal syndrome and hepatorenal syndrome (terms commonly noted in medical literature), but cardio-hepatic syndrome is also possible.

But it won’t stop at cardio-hepatic, in that an injured liver will pass the injury onto the kidneys.

“Yes — there seems to be a kind of feedback loop where poor heart function can lead to poor liver function — and kidney function — and then, the poor liver and kidney function leads to even worse heart function,” explains Dr. Pool, “because the body has fluids accumulate — mostly pulmonary edema and peripheral edema, but also ascites [abdominal fluid] — which overload the failing heart even more. This can lead to worse liver/kidney function…etc.”

What’s alarmingly vexing is that the very drugs that may help particularly frail patients survive have the potential to accelerate kidney injury, leading to a sooner death. In these cases…there’s a dead end no matter how you slice it. Doctors can:

Give the drugs and hope things turn around (no chance), and the patient dies within 72 hours.

Or…don’t give the drugs and at least, though the patient is terminal, they may live a few weeks.

Variables predictive of mortality include advanced age, pre-existing intrinsic kidney disease stemming from the chronic heart failure, pre-existing ejection fraction under 20 percent and presence of extensive coronary artery disease.

Good Liver Health Means Good Heart Health

“Accumulating evidence shows that acute as well as chronic heart disease can directly contribute to an acute or chronic worsening of liver function and vice versa,” says a paper in Current Heart Failure Reports (Poelzl et al).

“Heart disease” in this context refers to heart failure, not clogged arteries.

The paper continues, “Thus, it appears that hepatic congestion secondary to right-sided heart disease [failure] may prime the liver for ischemic insults from low cardiac output and reduced hepatic blood flow and oxygenation due to left-sided heart failure.”

A study (Gastroenterology & Hepatology, April 2013) notes that “Only about 5% of patients with hepatic disease and CHF will have clinically overt jaundice [yellow skin].”

But many will likely have an enlarged liver (hepatomegaly). “A smaller percentage of patients—ranging from a few percent up to 25%—will have cardiac ascites,” continues the report.

What’s interesting about the ascites (fluid buildup in the belly) is that liver impairment usually causes this.

So if someone has ascites and acute liver failure secondary to chronic or acute heart failure, there’s no way to visibly tell how much of this fluid leakage is directly from the liver vs. the heart.

It’s easy for a doctor to determine if the failing liver is secondary to pre-existing heart failure because other causes of acute liver failure (alcoholism-cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, local blood clot and poisoning) can easily be ruled out.

More on the Symptoms

“In the setting of acute liver failure due to congestive heart failure, clinical signs of the latter can be absent,” says a paper in the European Journal of Medical Research (Saner et al).

“Acute liver failure is defined as an abrupt onset of jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy [cognitive impairment which may include difficulty speaking], and coagulopathy [sticky blood] in the absent [sic] of pre-existing liver disease,” continues this paper.

“Cardiac decompensation can initially be undetected, and the usual signs of congestive heart failure may be absent. Both, chronic and acute congestive heart failure can lead to hepatic dysfunction.”

The critical threshold mentioned previously, or that tipping point that sends the liver over the edge, initiates a “cascade of events that ultimately results in hemorrhagic centrilobular necrosis,” i.e., death of liver cells.

Other possible symptoms are stomach pain, especially in the upper right quadrant, sleepiness, nausea and aversion to eating.