The kidneys get all the attention as the organ that fails secondary to chronic heart failure.

However, the liver, which the heart pumps 25 percent of its blood flow to, will also decline with chronic heart failure. Usually, the decline does not impair day-to-day function.

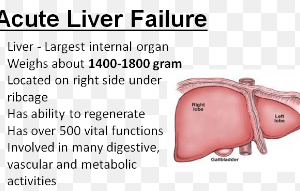

There are numerous causes of liver dysfunction, whether chronic or acute (sudden).

Chronic examples that are more known to laypeople are alcohol abuse, excess ibuprofen and poor diet.

Acute examples are viral infections and poisoning (e.g., Amanita mushrooms).

One-fourth of the heart’s blood gets directed to the liver, which is highly vascular. This large organ is greedy when it comes to blood flow for its proper function.

When the liver suffers as a result of reduced blood flow (which not only may occur due to a weakly pumping heart, but also a local obstruction such as a blood clot), this is called ischemic liver or congestive liver.

Longstanding heart failure can actually result in a sudden decline in liver function. The liver gives up the fight; it can no longer be productive on reduced blood flow.

However, subclinical (asymptomatic) decline will have already been in place from years of poor cardiac output.

Much more commonly, it’s noted in the CHF patient that their kidneys are impaired (chronic renal insufficiency) due to reduced blood flow. One-fifth of cardiac output is directed to the kidneys.

Poor Cardiac Function = Poor Liver

“Congestive hepatopathy is a term to describe when the liver becomes congested,” says George Ruiz, MD, former chief of cardiology at MedStar Union Memorial and MedStar Good Samaritan Hospitals, with expertise in the care of adults with advanced heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, congenital heart disease and heart disease during pregnancy.

“This can result from the ‘backup’ of pressure from a heart that is having a hard time filling, pumping or both.”

• Systolic heart failure: The pumping action of cardiac muscle is weak.

• Diastolic heart failure: The pumping action is good, but the chambers do not fill with enough blood, so hence, reduced blood flow throughout the body results.

• A person can have both systolic and diastolic impairments.

“When the liver becomes congested, it can lead to liver dysfunction, loss of appetitive and in extreme, chronic cases, scarring of the liver — also known as cirrhosis,” says Dr. Ruiz. “This can happen independent of alcohol and drug intake.”

If a patient presents to the emergency room with classic signs of acute liver dysfunction (jaundice or yellowish skin/lips/eyes, fluid buildup in the belly and impaired mental function), the ER physician is apt to presume an alcoholic origin.

A CT scan will be given to see what the liver looks like. Medical history, an echocardiogram and blood tests strongly play into the diagnosis.

If the patient has a history of CHF, and tests are negative for alcoholic cirrhosis, a viral infection, drug toxicity and poisoning, and there are no blood clots or tumors showing in the liver, then the logical conclusion is ischemic or congestive liver secondary to chronic HF – especially if the patient’s kidney blood test is worse than usual.

Usually, when a person dies of complications of chronic HF, it involves fluid buildup in the lungs and sometimes around the heart, causing a respiratory emergency.

Diuretic drugs are given to make the kidneys expel the fluid through urine. But typically, the patient has longstanding kidney disease – secondary to the CHF.

The diuretics can further damage the kidneys. Doctors are then tasked with finding the right balance.

Mortality rate is high in elderly people who are hospitalized due to respiratory distress due to fluid buildup (edema) in the lungs.

Liver Goes First

In a small number of CHF cases, the liver is the organ that suddenly develops problems. There may not even be much fluid in the lungs.

But an abrupt worsening of liver function is life-threatening. In acute liver failure, regardless of cause, the kidneys suffer acute injury.

So now the patient not only has a rapidly deteriorating liver, but also fast-declining kidneys.

In the case of CHF, the prognosis for such an elderly patient is exceedingly bleak.

How do you fix this?

You really can’t. You can’t give them a heart transplant because they don’t qualify due to age and pre-existing renal insufficiency.

Even if they were put on the transplant list, they wouldn’t survive long enough for the transplant. And even if they did, they wouldn’t survive the transplant.

They are deemed hospice status and will have days to weeks to live: end-stage organ shut-down secondary to longstanding heart failure.

So what’s the takeaway?

The best thing you can do to keep your liver and kidneys very healthy for many decades is to take great care of your heart. Take measures to avoid the development of CHF.

• Don’t smoke

• Prevent high blood pressure

• Limit processed and sugary foods; load up on fresh produce

• Get rigorous exercise

• If you suspect sleep apnea, get a sleep study to see if you have it, because untreated sleep apnea can lead to high blood pressure and CHF.

• Avoid excess sitting; it’s been linked to cardiovascular problems.

• And of course, another way to preserve good liver health is to avoid alcohol.

Dr. Ruiz has also treated patients with congenital heart disease and heart disease during pregnancy. From 2006 to 2007 he served as a White House Fellow and was a special assistant to the Secretary of Veteran Affairs.

Dr. Ruiz has also treated patients with congenital heart disease and heart disease during pregnancy. From 2006 to 2007 he served as a White House Fellow and was a special assistant to the Secretary of Veteran Affairs.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, fitness and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.