I initially thought it was a play on the word “artistic,” but there’s actually some truth to that.

The first time I heard the term “autistic,” it was in reference to a condition that a child could have. I don’t recall my age at the time, but I thought it was a variation of the word “artistic.”

It’s possible that my mind went in this direction because I’d heard the word “artistic” many times — by adults referring to my artwork.

So naturally, when I heard autistic child, I thought it meant a child with art talent.

At some point, however, I came to (incorrectly) understand that it meant a disorder in which young children are unable to communicate, not even with their parents, and are in their own little world.

The stereotypical behaviors were those of sitting in a corner for hours, rocking or performing other unusual upper body movements.

Other stereotypical behaviors included avoidance of eye contact, lack of speech other than maybe to express a need, and stiffening as babies upon being picked up and held.

In a 1969 episode of “Marcus Welby, MD,” Dr. Welby is chatting to the driver of a car who has a neurotypical child. He then notices another child in the backseat and greets the little boy.

But the boy’s eyes remain upward and he begins flapping his hands before his face. Dr. Welby then realizes that something is amiss.

The child is diagnosed with autism; the episode is about breaking through to him, and by the end of the episode, he’s able to state his name.

Then we have the autistic boy in the last episode of “St. Elsewhere.”

The boy is unable to effectively communicate and spends hours staring at a snow globe.

I grew up associating autism with the savant phenomenon, but also realized that not all autistic people are savants. Most aren’t.

Years ago I met two autistic savants who were able to quickly calculate what day of the week any date would fall on, and yet, neither were able to explain how they did it.

Autists have been known to reproduce on paper, down to the finest detail, land- and cityscapes after only one viewing.

I, too, can reproduce a scene or any inanimate object, down to the finest detail, with my favorite illustration implements: ballpoint pen, thin marker, rapidograph and pencil/charcoal.

However, I need to continuously be viewing the scene or inanimate object while I’m drawing!

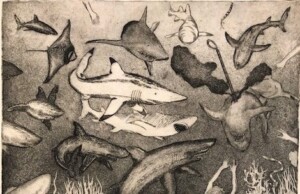

Etching for a college class by the author.

I can’t just look at an array of handyman’s tools spread on a table, then draw them — including rendering the appearance of shiny metal and wood — after looking at them only once.

I have to repeatedly look at them while my illustration implement moves on the paper. People were always astounded at how I could do this.

Yet here I am, totally astounded over how artistic autistic savant Stephen Wiltshire could replicate complicated architectural structures after seeing them only once.

So you see, it’s not a far leap for a child to at first think that autistic means artistic.

Over the past 25 or so years, there’s been increasing public awareness of the concept of varying degrees of autism.

This neurodevelopmental condition isn’t just about little boys who spin in circles for hours and can’t even ask their mother for a glass of milk.

It’s about a spectrum of traits, which means that many autistic people are 100% self-sufficient and can be in lines of work including that of lawyer, salesperson, software engineer, physician, actor, entrepreneur, teacher, psychotherapist and social media influencer.

In Level 1 ASD, the neurodivergent traits certainly don’t get missed, and in fact, can cause numerous disruptions in the quality of living (depending on multiple variables).

But usually they are not pronounced enough to impair that person’s ability — even as a child — to independently function in their world.

For instance, many a mildly autistic child can get through any school day without the need for an aide or some kind of assistance. Autism is not an intellectual disability.

However, that same child — who has no difficulty quickly memorizing their class schedule, showing up to class on time, turning homework in on time, sitting through class without causing disruptions (the troublemakers are almost always NTs), getting good grades and understanding what the teacher is explaining before most of his or her classmates do — will often find themselves alone on the playground during recess, completely flummoxed over why nobody wants to play with them.

They never get invited to birthday parties. Teachers give them a hard time.

When I was in ninth grade, my art teacher had a habit of suddenly telling me, out loud, for the whole class to hear, “You always look SO seeeerious.” Never mind that I was by far the most skilled artist in that room.

In geometry class, when the teacher told us to get into groups to work on a just-explained lesson….this was unsettling. Nobody wanted me in their group.

Ask a bunch of autistic adults (including those with late-life diagnoses) what lunch time during school was like.

Many will say they either ate their lunch in a bathroom stall, skipped it and instead spent the period in the library (though they may have snuck their lunch in there and ate it in an obscure corner where all the boring books were to guarantee nobody would catch them), or actually ate with a group of kids but felt very out-of-place, almost alien, every single moment.

So you see, those with mild ASD frequently fly under the radar while growing up, being labeled as socially awkward, shy, quiet, doesn’t get along with peers, over-imaginative, too sensitive, too insensitive, weird, brainy, geeky or disrespectful.

This is why mildly autistic kids will often go undiagnosed until adulthood, especially if they grew up decades ago, before the concept of spectrum started gaining traction.

In 11th grade biology, I was the only kid in my class who could identify the sex of fruit flies without a microscope.

I could look at the tiny things for only a few moments and know if they were male or female, while everyone else had to place them on slides and examine through a microscope. I’d always attributed this to my artistic talent.

But the more I learn about Autism Spectrum Disorder, the more I realize that this ability to detect a very faint detail was more likely due to my Autistry.

I consider myself an Artistic Autistic. But unfortunately, my passion for illustration fizzled out after I graduated from college. It was replaced by writing!

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

.