Patients with chronic heart failure often have insufficient renal function, thanks to reduced blood flow.

But what about liver dysfunction resulting from the reduced blood flow?

You’d think that, more so than the kidneys, the liver would be impaired in people with chronic heart failure.

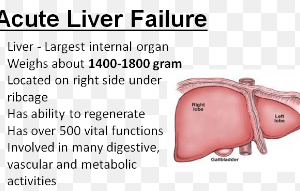

After all, 25% of the heart’s blood output goes to the liver, a highly vascular organ with hundreds of functions.

So let’s take a patient with chronic heart failure and reduced kidney function who one day starts developing signs that look like acute liver failure.

This patient never drinks (heavy drinking can damage the liver) and is negative for an infection or toxicity, as revealed by lab and imaging tests.

There are blatant clinical signs of acute liver failure (e.g., jaundice, bloated abdomen, altered mental status, severe weakness), but the test for kidney function also shows a worsening state. The liver enzymes, though, are elevated, but not that much.

Cardiorenal Syndrome and “Cardiohepatic” Syndrome

Acute liver failure, in the absence of other agents such as drinking, is so much less common an outcome of longstanding heart failure than is acute kidney failure.

It’s not uncommon for the chronic heart failure patient’s kidneys to start deteriorating quickly enough for family members to notice a global decline in function.

The BUN (blood urea nitrogen) test can show this decline via an increasing number getting closer to 100. As the number gets higher than 100, you know the kidneys are really struggling.

The elderly, frail patient at this point would need to be hospitalized, and from that point on, is in a dying process from end renal failure secondary to heart failure. The end renal failure may lead to aspiration pneumonia.

Old, tired kidneys that aren’t getting a good blood supply have a way of just giving up – both at the same time. This is acute cardiorenal syndrome.

Earlier in the course of the disease, heart failure patients are put on kidney management protocols, but there’s typically no mention of how precarious advanced heart failure is to the liver, nor is there education to these patients of what to look out for, for early signs of acute liver failure.

“The majority of the blood supply to the liver comes from the portal vein [located in the liver], but this too would be affected by heart failure,” says Daniel Motola, MD, a top board certified gastroenterologist and hepatologist providing same-day and next-day services in NYC with Gotham Medical Associates.

“I imagine that patients who suffer acute liver failure from cardiac failure may have either unrecognized chronic liver disease resulting from either fatty liver, alcohol or other liver diseases, including their heart disease,” explains Dr. Motola.

“It’s possible that they are tipped over the edge once the cardiac output drops below a certain level.

“Thus, there may be some underlying risk factor that is unknown that leads some, but not others, with heart failure to develop liver failure.”

The liver failure will lead to acute kidney injury. This is called hepatorenal syndrome.

But the term “cardiohepatic syndrome” is not part of the medical vernacular, even though this seems to be the pathogenesis for a small percentage of heart failure patients.

In addition to his liver transplant expertise,

In addition to his liver transplant expertise,