You know that long femurs are a curse for squatting exercises, but does this problem carry over to day-to-day activities?

As a former personal trainer and always-fitness enthusiast, this topic intrigues me.

If you clicked on this article you probably have long femurs (and a short torso) and struggle with the squat exercise.

But have you wondered just how much this anthropometry affects daily activities?

The long femurs and short torso body type, indeed, moves differently in real life.

But because real life movements aren’t the same as the back squat, people whose femurs are longer than their torso will not necessarily make a connection between why they must move a certain way, and their body proportions.

When trying to barbell squat, the person whose femurs are longer than their torso will know there’s a big problem.

That’s because it’s impossible not to notice that if you don’t lean your torso far forward in a barbell back squat, you’ll fall backwards.

In real life, the issue of falling backwards gets unnoticed because when a person with long femurs and short torso bends their legs to pick a heavy item off the floor — their hands on the object, or arms wrapped around it — prevents them from feeling the sensation that they’ll fall backwards.

Shutterstock/studioloco

They simply bend over, grab the item and lift it. In a barbell squat, you are not grabbing onto anything for support, so the tendency to fall backwards is glaringly obvious.

The exerciser is thus forced to think about limb proportions and biomechanics.

So if a person with long femurs and a short torso can, indeed, pick a heavy object off the ground, how is he or she affected by their anti-gym squat anthropometry?

It’s a matter of degree of range of motion.

Let’s take two people of equal height and weight, Mark and Rip.

Mark’s femurs are a lot shorter than his long torso. Rip’s femurs are a lot longer than his short torso.

However, both guys train hard and are strong. There are 10 heavy crates on the ground. About midway down on either side of each crate is a handle.

The proper way to pick them up is to squat (feet FLAT on ground), keeping the back upright, grab the handles and “lift with the legs.”

To make this easier to understand, imagine that Mark’s femurs are six inches long and his torso is two feet long.

He only needs to squat half-way (thighs parallel to ground) to reach the crate handles while still in an upright position.

His lift, then, consists of coming out of a HALF squat.

Imagine that Rip’s femurs are two feet long and his torso is one foot long.

Rip will fall backwards long before his squat gets half-way unless he bends his torso to practically parallel with outstretched arms.

He can also grab the top of the crate. However, this puts him in a position that makes it impossible to pick up the crate.

In order to lift it, his groin must be close to the crate. (Did you not picture this with Mark?)

If Rip simply leans over and grabs the handles, what happens to his body? He’s nowhere near a half-squat.

His torso is bent so far over that it’s well-below parallel and his back is totally rounded, butt poking high into the air.

He can pick the crate up this way, but it puts tremendous stress on his lower back!

If he tries to squat parallel while holding the handles, his long femurs get in the way; he can’t do it.

In order to keep his hands on the crate WHILE being in a parallel squat, he must distance his body from the crate, making it impossible to lift it.

The person with long femurs and a short torso has two choices.

He can either lift the crate from the position of being stooped way over (torso well-below parallel, back rounded, legs nowhere near a half-squat, butt sticking up into the air), OR —

He can get into a full “ATG” squat. This will enable him to be close enough to the box to get his hands on the handles, while keeping his back much more upright.

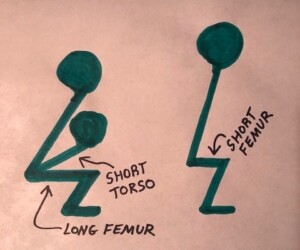

The illustration below will help you understand the general concept.

Who’s in a better position to lift that crate with their hands (assuming both have equal length arms)? The body on the left or right?

Close your eyes and visualize a man with super long femurs in a full squat, back upright, arms out in front holding onto the crate handles for balance.

Unless Rip has arthritic knees, this position is easily doable. Of course, the second he lets go of the handles, he’ll fall flat on his back.

To lift the crate, Rip rises from a full squat, straight up, back upright. The lift consists of a FULL squat.

- Mark picks up 10 crates; that’s 10 half-squats.

- Rip picks up 10 crates; that’s 10 FULL squats.

Rip must do more work! The same scenario occurs when they must set the crates down; Mark gets to do 10 half-squats, but Rip must do 10 FULL squats!

Though Rip may have stronger muscles than Mark, his inability to get into an efficient body position causes him to fatigue faster than Mark; the job is harder.

In summary, those with femurs longer than their torsos must perform full or three-quarter squats (depending on height of object to be picked up), to lift something off the ground with an upright back.

However, those with the opposite proportions get to do only half-squats.

And if the long femur person wants to do a half-squat, he has to forfeit the upright back!

There’s a third option for those with long femurs and a short torso: a wide stance with feet pointed out; this will enable a more upright back.

There’s a caveat: This shifts some work to the weaker adductor muscles (inner thigh).

Nevertheless, those with long femurs and a short torso can train hard and develop a very strong wide or “sumo” stance.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified through the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained women and men of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.