Everyone experiences twitching muscles.

Any voluntary muscle is capable of twitching.

This includes the eyelid, right above the lip, behind the ears, and of course, the larger muscles, including those located in the back, abdomen and limbs.

Fingers and toes may twitch from time to time as well. In fact, when digits twitch, it’s common to be able to actually see them in twitching motion.

Often, other muscles that twitch can also be seen twitching, including muscles on the top of the hand. In short, muscles, by nature, twitch.

For exercise enthusiasts, the most common sites of muscle twitching are the calves, arches of the feet, quads, hamstrings and glutes.

However, upper-body muscles also commonly twitch, such as biceps after performing pull-ups or grueling biceps curls; or chest muscles after bench pressing, pushups or some other rigorous chest routine.

Exercise is one of the most, if not the most, common causes of muscle twitching.

Shutterstock/bg_knight

However, the twitching normally does not occur during exercise. Sometimes, it occurs immediately following weight-bearing routines, such as pull-ups.

On the other hand, twitching may not start until the person finally comes to a complete rest at home. Cardio exercise can also induce twitching.

The medical term for muscle twitching is fasciculations, or fascics for short.

Ranking at perhaps No. 2 on the list of causes for fasciculations is anxiety.

Yes, muscles will often jump around a bit when you’re flanked with stress and anxiety.

Freepik.com, creativeart

Another cause is dehydration, though you may not be particularly thirsty.

Lastly, inadequate intake of calcium and magnesium is a classic cause of fasciculations.

Muscle twitching, to some people, feels good, kind of like internal massaging.

But to other individuals, fasciculations can be annoying, especially if the twitching rate is coming in at about one fasciculation per minute.

Some people experience several fasciculations per minute, for hours on end, even all day long.

Individuals have described the sensation as “worms crawling under the skin,” or “thumping.”

One particular area of the body may twitch a lot: a “hot spot” for fasciculations.

Common hot spots are calves and arches, because calves really do quite a bit of work from day to day, and our feet take a good beating on a regular basis.

Sometimes, twitches are body-wide. Interestingly, if a person starts worrying about the twitching, he or she will start twitching more.

In fact, many people who first start experiencing fasciculations in one body part, such as the feet, will then report that the twitching “quickly spread” throughout their entire body — only after they began worrying about it or focusing on it with too much wonder.

But are fasciculations something to worry about in the first place?

If fasciculations become annoying, you may become concerned that the twitching signals some kind of medical ailment.

This is akin to automatically concluding that an upset stomach means colon cancer.

However, in the case of a medical condition, the twitching is always accompanied by other symptoms of that condition. In other words, there is no illness that is characterized by just twitching.

When anxiety about fasciculations accompanies the twitching, other symptoms often appear: muscle cramping, some tingling, and what seems to be weakness. All three of these symptoms are caused by the anxiety.

Yes, muscle weakness in this case is imagined.

This is called “perceived weakness.” But if anxiety is severe enough, muscles really can lose their efficacy.

A classic example is when a person is under extreme duress, and can barely walk due to “buckling” legs.

Once the person begins lifting, running or hiking (and we all know how effective vigorous exercise is at eradicating anxiety), the perceived weakness typically disappears into thin air.

Notable muscle twitching is referred to as benign fasciculation syndrome, or BFS.

BFS is a fancy way of saying that someone has twitching muscles, usually accompanied by cramping or tingling.

The cramping often comes from tension in the muscles, sometimes from fasciculations; and tension from stress.

Muscle twitching in and of itself does not cause tingling. But worrying about the twitching can, since stress causes constriction of blood vessels in extremities, thereby reducing blood flow there!

Certainly, all athletes will get fasciculations sooner or later. After a rigorous hike or trail run, for example, a person will eventually settle down and relax, legs immobile.

Soon after, his or her legs begin twitching like mad. Movement ceases the twitching. But once inertia resumes, fasciculations resume.

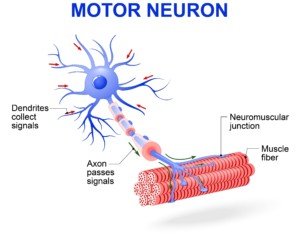

Just what causes the twitching in the first place?

Shutterstock/Designua

“Above all, fatigue is the reason for the muscle twitching,” explains Kevin Plancher, MD, a leading sports orthopaedist and sports medicine expert in the New York metropolitan area.

“The muscles are most likely overworked at this point. The nerves that send impulses to the muscles become fatigued as well, which can cause erratic firing of the muscles.”

Long exercise sessions cause lactic acid to build up, resulting in a lack of oxygen.

Dr. Plancher says, “This alters the way the muscles contract as well, possibly causing twitching.”

As mentioned earlier, cramping can be brought on by stress. But it can also be caused by an electrolyte imbalance in the athlete.

“In order for a muscle to contract, electrolytes play a key role,” says Dr. Plancher.

Cramping and twitching can result from increased amounts of sweating that follow exercise, he says.

Also, cramping — or what the athlete describes as such — can simply be caused by an over-worked or over-stretched muscle.

Fasciculations shouldn’t be a nuisance, once you realize that they are a normal part of muscle physiology.

But there are ways to manage fasciculations, for those who don’t like the sensation.

Dr. Plancher says, “Movement is a very good way to minimize the twitching. It helps the body move the excess lactic acid out of the muscles.

“Secondly, it allows the electrolyte levels in the muscles to normalize if they are unbalanced due to fatigue of the nervous system.

“Stretching the involved muscles will help as well. This relaxes the muscles.

Freepik.com/Racool_studio

“Increasing fluid intake can be key to minimizing these episodes, especially if electrolyte imbalances are the culprit.”

Try a banana or an all-natural electrolyte beverage.

Dr. Plancher also suggests gradually working into an exercise session, rather than jumping in with too much, too soon.

“Do not overload in the beginning. You will see less adverse reactions with a progressive program.”

Finally, work on ways to reduce the anxiety in your life.

Dr. Plancher explains that the muscles of an anxious person are often tight — as in too much tension.

“The muscles would be in a constant state of contraction that would overwork the muscle and cause fatigue just like in exercising muscles.”

If you’re having a hard time settling down, consider doing muscle-relaxing activities such as yoga and swimming.

Lastly, spend some time in a sauna for its detoxifying and calming effects.

Dr. Plancher is founder of Plancher Orthopaedics & Sports Medicine, and lectures globally on issues related to orthopedic procedures and sports injury management.

Dr. Plancher is founder of Plancher Orthopaedics & Sports Medicine, and lectures globally on issues related to orthopedic procedures and sports injury management.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, health and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of feature articles for a variety of print magazines and websites. She is also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical, health and cybersecurity topics for many years, having written thousands of feature articles for a variety of print magazines and websites. She is also a former ACE-certified personal trainer.

.