Here we go again: This time it’s psychiatrist Max Pemberton who claims autism can only exist “profoundly” and that an actual spectrum doesn’t exist.

Max Pemberton, a psychiatrist for Britain’s National Health Service, claims the following:

- “Autism has gone from being relatively rare to being everywhere.”

- A study published in 2018 by the universities of Montreal and Copenhagen concluded that if the trend of exponential autism diagnoses continues, within a decade there will be no separation between someone with autism and the average person – meaning we’ll all be classified as autistic.

- Dr. Pemberton’s Daily Mail article also says that Dr. Mike Shooter, a child psychiatrist and former president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, notes that autism is “vastly and dangerously overdiagnosed.”

Dr. Pemberton goes on to explain that social media has added fire to the “alarming trend” of more and more ASD diagnoses.

“It’s become a trendy label to medicalise simply not fitting in or being a bit shy and different,” continues the doctor’s article.

Since when is a diagnosis of autism trendy? Ask 10 individuals who were diagnosed as adults, how people talk to them once they disclose their diagnosis.

The majority will probably tell you they get talked down to or spoken to as though they’re children. Who bloody hell wants that?

And how on earth is an autism diagnosis a medicalization? After all, there is NO medical treatment or medical management for autism.

An autistic person may undergo applied behavioral analysis, but this isn’t medicine.

If they’re taking prescribed pharmaceuticals, these are for different conditions such as ADHD, anxiety or depression.

Dr. Pemberton, who’s a well-known medical journalist (I wonder if his good looks have contributed to his popularity and therefore ability to convince people), adds that the “over-diagnosis” is offensive to autism; that this neurotype “can be hijacked by people who like coding” or feel awkward at parties.

Oh really? This is a pretty broad and simplistic argument for his perspective.

Wonder what this person’s relevant credentials are. For sure, they don’t have any credentials in basic writing skills. That aside, nobody’s saying that a neurotypical can’t be odd or “different” in some ways. But in autism, the individual has always FELT different from other people. This is not the usual case with neurotypicals who are perceived by others to be quirky or who know when they’re putting on a quirky act.

The psychiatrist admits that those who claim to be autistic do indeed have problems.

But he then says that autism traits such as social deficits and “obsessional behavior” are not unique to ASD; that “they’re present in many psychiatric conditions.”

Well, I’d sure like for him to name one, let alone “many,” condition for which obsessional behavior is a hallmark sign.

Now, “obsessional behavior” can mean different things to various people.

Yes, someone with schizophrenia may display what appears to be obsessional behavior, such as a preoccupation with safeguarding their apartment from imaginary enemies.

But in autism, for which I have a clinical diagnosis, obsessive behavior would usually refer to obsessions or hyperfixations on our beloved passions, and we derive joy or fulfillment by engaging with these “special interests.”

One might say that I definitely had had an obsessional interest in the profession of tree care work when, at age 45, I mindlessly trespassed onto a stranger’s back porch to observe a tree cutting operation in the yard behind theirs.

Only when the resident came up from behind me and asked whom I was, did I realize what I had done.

The sound of a wood chipper would make me drop home-based deadline work on a dime and venture outside or jump into my car to find out where the chipper was so that I could watch the men “chipping” tree branches. Yup, you could say I was a bit obsessed.

Dr. Pemberton explains that an autism label “removes responsibility and agency from the person.”

That’s not why I, and many other adults I’ve spoken to and read about, have sought an autism assessment.

“People love a label,” continues the article, “especially if they think it means they don’t have to change and can be used as a foil against criticism of their behaviour or shortcomings.”

Perhaps he’d like to produce the data that shows that most people with adult autism diagnoses use this to excuse atypical or offensive behaviors.

But I’ll admit: One time I used it to get a paper cup from Qdoba after they said only the plastic cups were free (I claimed a sensory issue with plastic).

However, this hardly qualifies as a foil against criticism for shortcomings.

I also used it to gain early boarding on a flight.

But if someone thinks I’m acting like an ass, I will NEVER say, “Well that’s because I’m autistic.” (In fact, their perception of me might be more about them than me!)

And if I myself see an Autistic acting like an ass, I will never give them a pass just because they’re on the Spectrum.

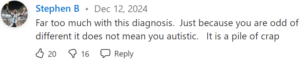

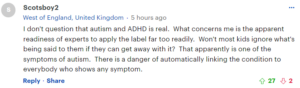

Comments such as the one below are exemplary of daft thinking:

This person has focused on the autism sign of ignoring people who are talking to them. But he fails to distinguish between ignoring a loving voice offering the child a treat and ignoring an irate voice telling the child to put his toy away. Yes, it’s within normal behavioral range for a child to ignore the latter type of communication. But “normal” children do NOT ignore the first example!

Why can’t a condition have mild forms?

Dr. Pemberton’s article includes comments from readers who agree with him.

Don’t people, along with this psychiatrist, understand the concept of spectrum, grades or levels?

Yes, it’s true that a person is either diabetic or not; either pregnant or not; either has cancer or not.

But there are many conditions that have degrees of involvement, such as depression, anxiety, ADHD, overweight, arthritis and sleep apnea, to name a few.

So why can’t Autism Spectrum Disorder also be more widely recognized as coming in degrees, grades or levels?

According to the DSM-5, the U.S. mental health specialist’s guide for classification of psychiatric conditions, autism is considered a spectrum that comes in three levels: 1, 2 and 3.

Many Autistics don’t like the reference to “high functioning” or even “mild” autism, though it seems common for parents to refer to a child as having “severe” or “profound” autism.

Ironically, in the article, Dr. Pemberton indeed says “profound autism,” which implies that he admits that this neurotype comes in a milder or less-impacting form!

Those who make it into adulthood before their autism diagnosis, who got through school without special assistance, who obtained a college degree without a personal aide, who never needed support systems to learn how to live independently, who’ve had a lengthy professional career – would be classified as having Level 1 ASD.

This doesn’t mean that those with “high functioning” autism don’t have many of the same experiences as do those with “real” autism.

Despite successes, they’ll tell you they’ve had struggles all throughout their life.

Plus, we “mild” Autistics, like “classic” or “real” Autistics, commonly engage in repetitive behaviors, also known as stimming.

The difference in the vast majority of cases is that we suppress it in public.

We have all sorts of so-called deficits or impairments when it comes to social skills, and have all sorts of peculiarities that are part of the autistic experience such as sensory issues, a tendency towards literal thinking, over-analyzing, overthinking, atypical experiences with eye contact, peculiar mannerisms, unusually intense fixations on objects, and so much more.

Sure, no one Autist comes with every single trait that’s ever been associated with autism; not all of us have meltdowns in response to big sudden changes; not all of us feel physical pain with eye contact; not all of us find fluorescent lighting averse or different foods touching on our plates unbearable or have monotone voices.

But it’s entirely possible to hit the minimum criteria for an ASD diagnosis without the condition rendering us significantly impaired to the point where we need frequent one-on-one support.

Again, why can’t the concept of varying degrees apply to autism?

©Lorra Garrick

If you want to call this different levels, then fine. If you want to call this a variation in support needs, then fine: low support needs vs. high support needs.

The point is that a diagnosis of ASD doesn’t have to be confined to those who are nonverbal and who can’t be left unsupervised for more than 30 minutes.

Furthermore, many Level 1 Autists will tell you that they HAVE endured serious struggles, despite having a lot of outward success.

For example, my biggest deficit has been in relating to or connecting with people.

None of my family members, who know of my diagnosis, would consider my social deficits as only mild.

It’s a pretty serious, significant thing when all your life you have never fit in.

Yes, that’s some pretty heavy stuff that Dr. Pemberton’s article dismisses as mere social awkwardness.

Of course though, there are plenty of “socially awkward” or introverted people who would never meet the criteria for an ASD diagnosis.

But remember, this doesn’t mean that Level 1 ASD (minimal support needs) is a make-believe condition or is less valid or less real than the so-called classic autism (Level 3).

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder and subsequently has developed an intense interest in ASD.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder and subsequently has developed an intense interest in ASD.

.