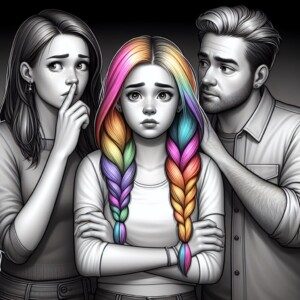

If your young child was diagnosed with autism and you keep this a secret from them, it can cause a lot of harm. An autistic woman to whom this happened explains why.

A child psychiatrist told my parents he thought I was autistic when I was seven. Sure wish they would have told me.

Instead, my parents did their typical dance of deny and pretend everything is okay.

My mother started pushing me to spend more time with “friends,” meaning, the daughters of her own friends.

My parents started pushing me away from them, insisting I should stand on my own two feet more, be more independent, less shy, less needy.

Which is a totally insane thing to tell your seven year old child, by the way.

None of these tactics made me any less different. Of course. I remained someone passionate about wild animals and environmental science, someone who could confidently talk politics with much older adults and hold my own in a debate.

I remained someone who looked at the children around me and thought how irrational, arbitrary and cruel were the rules they seemed to live by.

They didn’t understand me, and the feeling was extremely mutual.

There was the time a girl told me I was talking too much about horses and should stop, and I wondered what on earth else there was to talk about.

The time I tried to make other students I was paired up with like me by writing one of them a note about how sad and lonely I was, which went over about as you might imagine.

There was me, in third grade, writing my first novella in a composition book on my desk during classes, or reading under my desk when I thought no one was looking.

When I say I was unpopular, I mean literally no one wanted to play with me.

The saddest thing is, I blamed myself. Everyone else blamed me, so I did too.

It never occurred to me that there was a name for what I was going through, that other kids all around the world might be experiencing something similar.

I felt like I was alone in the world, and I thought that must be true.

I always say now that horses raised me. What I mean is, I bonded with the horses at the stable where I rode, and that bond was more parent-child than anything I experienced from anyone else.

I was drawn to the mares especially, to the horses who were lonely or neglected, angry and misunderstood. They became my mothers, my aunties, my friends, my sisters.

- I understood them, and they understood me. I knew that when I was with them, I was safe.

- That safe feeling never felt entirely present with any other human being.

To this day, I can read horses’ body language better than I can read other people’s. I know what they need without any need for words.

I know when they are trying to be affectionate vs. demanding vs. playful vs. needy.

They respond to my needs without turning me away, without judging me for having emotional needs, and this gift of respect and kindness saved my life.

The problem is, horses are not humans.

I was a human girl, with no one to teach me how to be a person. My mother mocked and berated me for shining too brightly or having needs she did not find appealing.

My father’s anger was inappropriate and scary, and his needs were the center of the family universe.

Both parents were abusive. When I wandered out into the human world and other peers abused me too, it felt like only more of the same. It felt like what I had learned to believe that I deserved.

Without understanding why they were so cruel to me, or what about me was so different, I became silent, scared, unsure.

I tried to do what everyone else was doing, tried to study their ways of interacting like a manual, which of course did not work.

My anxiety and fear of others was so high that I did not do a long list of things I wanted to try, like learn an instrument, sing in the advanced choir, try different forms of dress and self-expression.

I did not date until college, and even then, as little as possible.

Letting anyone know me seemed incredibly stupid. It seemed likely to end in disaster, like so many other attempts at connection had.

In my elementary school, there was a room for all the disabled children. The boy with trouble controlling his anger, the kids with very overt learning disabilities, the girl who was developmentally delayed.

To me, for the longest time, that is what disability meant. Some part of me felt that I belonged there with them, but that felt like a spiritual death, like giving in. I refused.

Disability comes for us all, whether we like it or not.

I have spent much of my life fighting off flare-ups of one or the other of my chronic illnesses. These flare-ups have become much worse in recent years.

I have lost or had to leave multiple jobs, lost friendships, lost romantic possibilities, because of my physical health problems.

I am 100% convinced these flare-ups are tied to stress, and particularly, to the emotional stress of being othered and bullied and harassed and rarely safe with other people.

To this day, people who barely know me call me arrogant or entitled for speaking plainly about my own needs, for standing firmly in my own space.

Part of me knows they are simply envious of the self-respect I have, so hard-won, and unable to claim their own voices and stand in their own space.

Yet I am so sensitive, so deeply in need of just a few precious people to believe I am valuable, that I am needed.

Rejection after rejection can pile up in a person, and eat away at you over the years.

I am in my mid-30s, and I am only now finding my autistic voice. My larger struggle is believing that anyone wants to hear it.

Don’t Keep Your Child’s Autism a Secret

I am building relationships with people who self-identify as autistic or neurodivergent, people who are able to understand me.

I know now that a lot of what I perceived in myself to be pathology was simply diversity.

I know now that people who mistreated me, people who still mistreat me, are demonstrating something about themselves in so doing, and not about me.

Community is so key. Finding people online who are like me. Meeting people in real life who value neurodivergence and value disability, people who don’t see me as a broken version of someone else — but instead, as a version of myself that still needs healing.

So many people are so afraid of autism.

My parents preferred to see me as someone with depression or OCD, someone whose difference was a mental health issue that could be treated.

They are not alone. Autism is still listed in the DSM, the big book of psychological disorders.

Medical doctors tend to see autism as a genetic curse, and psychiatry sees us as a problem to be solved through therapy and the right medication.

Neither of these things is true. We were born different, not broken. Our feeling of brokenness comes from how others have treated us and the harm that they have done.

My happy autistic self has very little in common with how I behave when I am hurting and afraid of new harm.

People may not understand us, but that’s all right – they don’t have to. We can offer ourselves understanding and seek that understanding in each other.

Yet I am so sensitive, so deeply in need of just a few precious people to believe I am valuable, that I am needed.

Rejection after rejection can pile up in a person and eat away at you over the years.

I am in my mid-30s, and I am only now finding my autistic voice. My larger struggle is believing that anyone wants to hear it.

As a professional writer, Ariadne Wolf works cross-genre in creative nonfiction, fantasy and historical fiction. Having an MFA in creative writing, Ariadne’s publishing credits include DIN Southwest Literary Magazine, Ashoka University’s Plot Number Two, and others, and has been awarded residencies with Alderworks, Sundress Academy for the Arts, and Rockvale, among others.

As a professional writer, Ariadne Wolf works cross-genre in creative nonfiction, fantasy and historical fiction. Having an MFA in creative writing, Ariadne’s publishing credits include DIN Southwest Literary Magazine, Ashoka University’s Plot Number Two, and others, and has been awarded residencies with Alderworks, Sundress Academy for the Arts, and Rockvale, among others.

.