My parents first noticed that something was wrong with my skin when I was three years old.

We had recently immigrated from the hot and humid climate of India to the seasonal climate and dry winters of New York.

They noticed that I was starting to develop itchy, scaly skin on my arms and legs, but when they brought me to a pediatrician they were told that my skin was simply “extra dry.”

I was prescribed Aquaphor to help—it didn’t. It wasn’t until I was seven years old after visiting several other physicians that I was finally accurately diagnosed with congenital ichthyosis (CI), a rare inherited skin disorder.

Ichthyosis vulgaris. Gzzz/CC BY-SA 4.0/creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>/ Wikimedia Commons

There are several forms of CI that develop as a result of different genetic mutations, each causing scaly and flaky skin that can lead to chronic itching, an inability to sweat, a reduced range of motion and a high risk of secondary infections.

Without getting a genetic test, there was no way to know which form of the disease I had, and thus no way to confirm what medications or topicals might best relieve my symptoms.

I tried countless lotions, creams, emollients and keratolytics, but none of them helped — and there is currently no approved treatments for CI (as of 2022).

Perhaps the hardest part of having ichthyosis growing up was that other kids would tease me about how my skin looked, calling me names like “Lizard Skin.”

I made any effort to cover my dry, ashy, scaly skin by wearing sweatpants nearly every day, no matter how hot outside it was, which in the warmer months seemed to draw just as much attention from my peers.

By 2019, I was attending Rutgers Medical School and studying in a dual MD/PhD program when my curiosity increased about what research was available about ichthyosis that might be able to help and provide answers.

I decided to send a saliva sample to the National Registry for Ichthyosis and Related Disorders for genetic testing to learn which type of the disease I have and hopefully, find better ways to manage my symptoms.

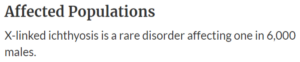

The test results reported that I have X-linked congenital ichthyosis. Finally having a specific name for my disease brought me relief and a greater sense of belonging and purpose.

Growing up I often felt isolated and like the only person in the world with ichthyosis.

Now I know that there are many other people like me going through similar experiences, and that there are treatments in development that might be able to address the underlying cause of my condition.

I enrolled in a clinical trial conducted by Timber Pharmaceuticals evaluating the potential of a topical formula to treat CI, which has allowed me to be proactive in helping find treatments for the disease.

I was also recently given the opportunity to speak at a national conference hosted by the Foundation for Ichthyosis & Related Skin Types (FIRST) about my experience with CI and participation in a clinical trial.

The experience was extremely rewarding, and I hope it showed others living with ichthyosis that they are not alone.

As an aspiring pathologist, I plan to continue advocating for awareness of ichthyosis as both a physician and patient and be as active as possible in helping move research efforts forward.

For more information: Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types

Saiaditya “Aditya” Badeti was born in Machilipatnam, India. At three he moved to New York with his parents. After developing itchy, painful scales on his skin, Aditya was diagnosed with congenital ichthyosis at seven. He now shares his story to build awareness of this rare genetic skin condition.

Saiaditya “Aditya” Badeti was born in Machilipatnam, India. At three he moved to New York with his parents. After developing itchy, painful scales on his skin, Aditya was diagnosed with congenital ichthyosis at seven. He now shares his story to build awareness of this rare genetic skin condition.