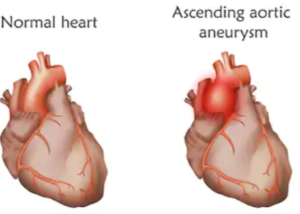

Dr. John Elefteriades, leading aortic disease surgeon, weighs in on the danger of deadlifts in people with an aneurysm of the aorta.

Though most aortic aneurysms affect older people, younger adults can be diagnosed with an aortic aneurysm, and older adults do lift weights for fitness and strength gains.

Thus, it is perfectly logical to wonder just how dangerous the deadlift is for a person with an aortic aneurysm.

Dr. Elefteriades is a weightlifter and also is William W.L. Glenn Professor of Surgery, and Director, Aortic Institute at Yale-New Haven, New Haven, CT.

Dr. Elefteriades refers to the deadlift as a “dangerous exercise” for a person with an aortic aneurysm.

The deadlift is especially dangerous because it requires the use of so many muscles.

Thus, at heavy weights (relative to the athlete’s strength, of course), this exercise has the potential to cause a rapid, extremely high increase in intrathoracic pressure.

Can a person, with aortic aneurysm, do deadlifts at a non-heavy weight?

After all, a deadlift refers to a type of joint motion, not to an amount of weight lifted. You can do a deadlift with a broom stick.

Dr. Elefteriades advises that an athlete with an aortic aneurysm limit a deadlift to just one-half his body weight.

As a former certified personal trainer, I’m initially thinking of the concept of half one’s body weight.

Suppose a new client of mine weighs 405 pounds: a morbidly obese person. This person has an aortic aneurysm less than 5 cm and not meeting surgical repair criteria.

According to the half body weight rule, this client gets to do deadlifts with a 200 pound barbell.

He won’t be able to at first, but according to the half body weight rule, it’s a safe goal to work towards.

Now suppose I get another client who’s been training for years and weighs 180 pounds, but is solid muscle.

He hires me to help him lose 10 pounds of body fat for a more chiseled appearance, and he’s so strong he warms up with a 200 pound deadlift.

Then he learns he has an aortic aneurysm (under 5 cm) after having a routine coronary calcium score test.

According to the half body weight rule, that 200 pound deadlift warmup is very off-limits, even though it’s easy for him to do.

Meanwhile, my 405-pound client, over time, has worked his way up to eight repetitions with 200 pounds — and he strains with every rep, barely completing the eighth one.

The 180-pound guy, because of his light body weight, gets “punished” for being only 180 pounds by the half body weight rule, being limited to just a 90-pound barbell: a total insult.

Something really doesn’t sound right here, because there would be significantly more intrathoracic strain (and hence a blood pressure spike), in the 405-pounder as he strains, struggles and grunts his way through eight reps at 200 pounds in the deadlift.

Whereas for the 180-pound man, a 200 pound deadlift would be a walk in the park, and hence, very little blood pressure increase.

So rather than a half body weight rule for aortic aneurysm, I wondered about a “no straining” rule that is based on subjective experience, rather than a numerical value.

Dr. Elefteriades explains, “The half body weight rule is for the average individual. There will be a moderate amount of strain for the amateur bench pressing half his weight.”

Though this article is about the deadlift, Dr. Elefteriades’ response applies to any major compound weightlifting exercise.

He continues, “A trained athlete can lift more to achieve a similar amount of strain.”

My 180-pound client might have to deadlift 300 pounds (1.6 times his body weight!) to experience the same degree of straining as my 405-pound client.

Dr. Elefteriades continues, “However, trained competitive bodybuilders achieve the highest aortic pressures ever recorded—up to 380 mmHg—normal is 120 mmHg.”

Even the sickest patients in hospital cardiac care don’t have blood pressures this high.

He adds, “We just advise prorating other exercises to the same perceived strain as with bench pressing 50 percent of body weight.”

The smaller the muscle group worked, continues Dr. Elefteriades, such as in triceps push-downs, the less strain even with max efforts, and hence, the less of a blood pressure rise, when compared to big compound movements like the deadlift, barbell squat and, of course, bench press.

So when it comes to the deadlift and aortic aneurysm, what’s the final verdict?

Well, suppose I get a third client; he too weighs 180 pounds but he’s not as strong as the other lightweight guy, but he’s been training for a while nonetheless and strains to deadlift 160 pounds eight times.

He’s just been diagnosed with aortic aneurysm; the 160-pound deadlift sets are over.

However, he easily knocks off a set of eight deadlifts at 115 pounds. No straining whatsoever. He whips through these quickly without a reduction in tempo.

According to the “no straining” rule, this is safe for him. For the other lightweight guy, a comparable easiness of effort is achieved at 200 pounds—making that safe for him.

Formerly the chief of cardiothoracic surgery at Yale University and Yale New-Haven Hospital, Dr. Elefteriades is working on identifying the genetic mutations responsible for thoracic aortic aneurysms. He is the author of over 400 scientific publications on a wide range of cardiac and thoracic topics.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified by the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained clients of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

Lorra Garrick is a former personal trainer certified by the American Council on Exercise. At Bally Total Fitness she trained clients of all ages for fat loss, muscle building, fitness and improved health.

.