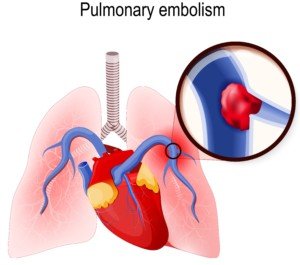

A pulmonary embolism is suspected, and the patient is being taken to the CT scanner to confirm this.

The D-dimer was positive and the patient is exhibiting the classic symptoms of a pulmonary embolism.

But the CT scan is needed for a verification before any powerful clot-busting drug is given. Doctors also need to see where the clot is specifically.

Yet on the way to the CT scan suite, the patient could go into cardiac arrest from the pulmonary embolism.

I wondered why isn’t the clot-busting drug immediately administered, right there in the hospital room — at least at a lower level — and THEN take the patient for his CT scan?

After all, it takes time to get to and on the CT scanner bed, take the image, then get a doctor to read the image results.

Certainly, the pulmonary embolism can cause death while the patient is enroute to the CT scanner or even during the scan?

Regarding the hospital patient presenting with sudden difficulty breathing and chest pain, “Clinically this scenario is one with a high index of suspicion for a pulmonary embolism,” says Seyed-Mojtaba Gashti, MD, a board certified vascular surgeon with Broward Health Medical Center in Florida.

“Of course if the patient is on a cardiac monitor, you can look for tachycardia, EKG changes with signs of right heart strain, etc., to strengthen that suspicion.

“In most cases what you do next is start anticoagulation with IV Heparin immediately if it is not contraindicated; you do not need a confirmation with a CT to start treatment.”

Anticoagulation drugs are contraindicated in patients prone to internal bleeding.

Dr. Gashti explains, “In certain post-op patients such as spine surgery or neurosurgical patients, thrombolytics — clot busting drugs, and to some extent even Heparin is absolutely contraindicated because of risk of bleeding.”

Filter Can Prevent Pulmonary Embolism

“In these patients, you would place a filter, and if they are not in cardiac shock, you would support them.”

This filter (shown below) will prevent any deep vein thrombosis from getting into the lungs and embolizing.

IVC filter. BrusBlaus/CreativeCommons

Other patients may have hemodynamic problems. “If they are hemodynamically unstable, then they will need surgical thrombectomy — mechanically removing the blood clots (from the lungs),” says Dr. Gashti.

A patient who’s hemodynamically UNstable is NOT necessarily at risk for internal bleeding from thrombolytic drugs. Hemodynamics refers to primarily blood pressure.

“In a patient with hemodynamic instability in whom thrombolytics are not contraindicated, you can start IV thrombolytics, but this is not as effective as performing an angiogram and placing a catheter into the pulmonary artery where the blood clot is and delivering the medicine directly there; this of course requires a trip to the angio suite.”

This procedure is called intra-arterial infusion (of the thrombolytic drug), and is not to be confused with the surgical thrombectomy, which involves opening the chest, accessing the pulmonary artery and physically removing the blood clot—a major surgery.

Two Ways to Deliver Thrombolytics

IV and intra-arterially (through the femoral vein in the upper leg, feeding a catheter up to the pulmonary artery and delivering the clot-busting drug).

Dr. Gashti emphasizes that “in a patient with suspected or confirmed pulmonary embolism, who is hemodynamically stable (and not at risk for internal bleeding), all that is needed is systemic anticoagulation (which can be delivered via IV or intra-arterially). Most PE’s will not be fatal.

“So as you can see, this is not a condition where one treatment fits all. It really all depends on how the patient is doing.

“As you correctly mentioned, some patients are not stable enough to travel to the CT scanner, but a CT is only done for confirmation.

“If you suspect it, then treat it and worry about confirming it later.”