Autistic adults tell of the rude comments they’ve gotten in public about their stimming behaviors.

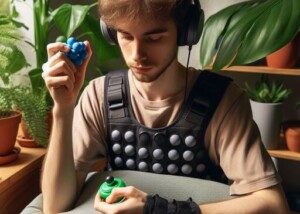

What is stimming? Stimming is another name for self-regulating, repetitive motions, also called self-stimulatory.

Common examples in autism are rocking, hand flapping, finger flicking, pacing, spinning, jumping, toe walking and humming.

However, there are probably as many ways to stim as there are designs of snowflakes!

A stim can be small and discreet, or it can be quite obvious. However, a “micro-stim” is just as much a self-regulating repetitive behavior as is a “big stim.”

An example of a micro-stim is that of repeatedly rubbing a pinky nail along one’s palm. This will go unnoticed when in public.

Another small discreet stim is that of repeated contractions or tightening of one’s calf muscle while seated.

A big or flamboyant stim that everyone in the room will notice is that of elevating both arms bent at one’s side and flapping the hands.

Autistic people who have zero to low support needs (Level 1) are far more likely to consciously suppress public stimming than are those who have high support needs (Level 2 and Level 3).

However, not all Level 1 Autists conceal or suppress stimming in public.

“People have seen me stimming in public and said rude things — to which I proudly explain I am autistic, with no hesitation,” says Angel Durr, diagnosed with ASD at 33, who’s a consultant and entrepreneur, and expert in automated technology solution design.

Angel explains, “I think educating people so they know this [rude comments] isn’t appropriate is key.

“One of the biggest stims I have is pulling my hair when I’m overwhelmed, and I often get told to stop destroying my hair because people don’t understand why I do it.

“I will comb my fingers through my hair and it gets pulled out in the process

“People normally just look at me and ask me if I am okay who don’t know I am autistic.”

Hair is a built-in stim for some autistic people. When I was around 12, for reasons unknown, I developed a compulsion to pluck the hair out of my scalp at the top of my head.

It provided some sort of self-regulation. For a few months I did this, and nobody knew about it.

This seems to have been a stimming behavior, rather than an obsessive compulsion disorder.

It’s not that I believed pulling out my hair one strand at a time would prevent bad luck or bring me good luck.

Rather, it was … self-regulating. What more can I say? It’s possible I did it around other kids during class — as it could’ve easily gone unnoticed — but I don’t recall either way.

One day I ran my fingertips over the area and felt a bald spot with stubble – and stopped cold turkey.

However, in either ninth or tenth grade, while writing something in my notebook, the girl who sat in front of me turned around and began watching me.

She asked, “Are you chewing gum?”

I immediately realized why she wondered about this. I had been chewing on the back of my tongue.

This is my earliest memory of this habit; but it’s obvious that this wasn’t the first day I’d been doing it, either.

I got busted! From that day forward, I’ve made a point to avoid chewing on my tongue when around other people.

But I kept doing it in private. To this day I still do it. It kicks up subconsciously and there are times I’ll do it all day long.

And no, my tongue does not get cut up. It’s a gentle “chewing” or gliding motion with my back teeth. I often do it while stimming with my hair – not pulling it out, but sniffing wads of it pressed against my face.

Needless to say, I never stim with my hair in public.

I won’t rock in public, either, even though I do a lot of rocking at home.

I doubt I’ll ever reach a point – like more and more autistic people are doing these days – of openly big-stimming in public.

We may never reach a point in society in which ALL kinds of stimming are socially acceptable.

Neurotypicals often wonder why autistic people — who fully realize which stims are socially unacceptable or which would make them seem “weird” — don’t just suppress these stims when in public.

Angel explains, “I normally mask it in public, but I get really overwhelmed in large crowds and can’t help it.”

Dr. Angel Durr obtained her PhD in information systems from the University of North Texas in 2018. She is an autism speaker focused on DEI, data, and entrepreneurship and is on speakerhub.com. Angel has a nonprofit called DataReady DFW that focuses on data literacy initiatives, and consults in strategic analytics.

Dr. Angel Durr obtained her PhD in information systems from the University of North Texas in 2018. She is an autism speaker focused on DEI, data, and entrepreneurship and is on speakerhub.com. Angel has a nonprofit called DataReady DFW that focuses on data literacy initiatives, and consults in strategic analytics.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Lorra Garrick has been covering medical and fitness topics for many years, having written thousands of articles for print magazines and websites, including as a ghostwriter. She’s also a former ACE-certified personal trainer. In 2022 she received a diagnosis of Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder.

.